A week into turning 75, and completing five decades as a writer, Shobhaa De meets mid-day to say why she chose to discuss food, not scandals, in her new memoir

Writer-columnist Shobhaa De says she wanted to be reflective, and non-judgmental in her new memoir. Pic/Sameer Markande

The last time we saw a flaming sunset, it was at Shobhaa De's Cuffe Parade home before the pandemic, when the world was freer. A lot has changed. Some things have, however, stayed as is. Like the view from the window of her residence. Except, that when we arrive on a weekday evening, the sun is hiding behind the jute roller blinds. The winter light—admittedly harsh—forces us to settle in its warm veiled glow, even as mid-day photographer Sameer Markande guides De across her sprawling drawing room for pictures.

ADVERTISEMENT

It's been a surreal week for her. On January 7, she celebrated her 75th, at her Pune home, surrounded by friends and family. “No celebrities,” she tells us. “Except Elvis Presley”. She speaks of a connection she feels with the King of Rock and Roll, whose birthday falls a day after hers. His rebellious personality was after her own heart. To meet him in flesh and blood, was a dream she nursed. And then, she happened to catch a performance by famed Elvis impersonator, Mehmood Curmally. She knew right then that it was going to be an Elvis-themed birthday party, which she called Jail House Rock.

De with her children Aditya, Anandita, Avantikka and Arundhati. “The Brood functions as a collective. It’s a tumultuous, fraught equation given how opinionated and outspoken all of us are. We are one another’s gurus, therapists, counsellors, sounding boards, anti-depressants and occasionally double up as cans of Red Bull,” she shares in the book

De with her children Aditya, Anandita, Avantikka and Arundhati. “The Brood functions as a collective. It’s a tumultuous, fraught equation given how opinionated and outspoken all of us are. We are one another’s gurus, therapists, counsellors, sounding boards, anti-depressants and occasionally double up as cans of Red Bull,” she shares in the book

Her new memoir, Insatiable (HarperCollins India), draws from this chutzpah for life, revisiting the post-pandemic year of 2022, and how it was filled with family, friends, and food (a whole lot of it). We are compelled to ask at the outset, why she didn’t choose to write her autobiography, especially at a time when the likes of Prince Harry have made it fashionable. “I didn’t want it to be a standard memoir. Most people anyway write deathly, boring accounts of their life.” We’d have imagined a juicier read from De’s stable; a tell-all packed with eccentricities and controversies she witnessed, akin to her Stardust editor days. “That was never the intention. It’s a cheap shot at success. It’s exploitative. Every time I have been approached [to write a tell-all], I have asked myself the three-letter question. W-H-Y? The answer comes to me immediately,” says De, “I wouldn’t like to be at the receiving end of someone else’s recollections of me, which may or not be accurate. And anything that makes me uncomfortable, I wouldn’t want to do it to someone else.”

De says she wanted this book to be reflective, and non-judgmental. “And to do that, I didn’t want to go back 75 years, because that would have been very tedious.” She chose instead, the 12 months of the calendar year to direct her chapters, while creating a portrait of people and experiences from her past and present, much like a diary entry and yet not.

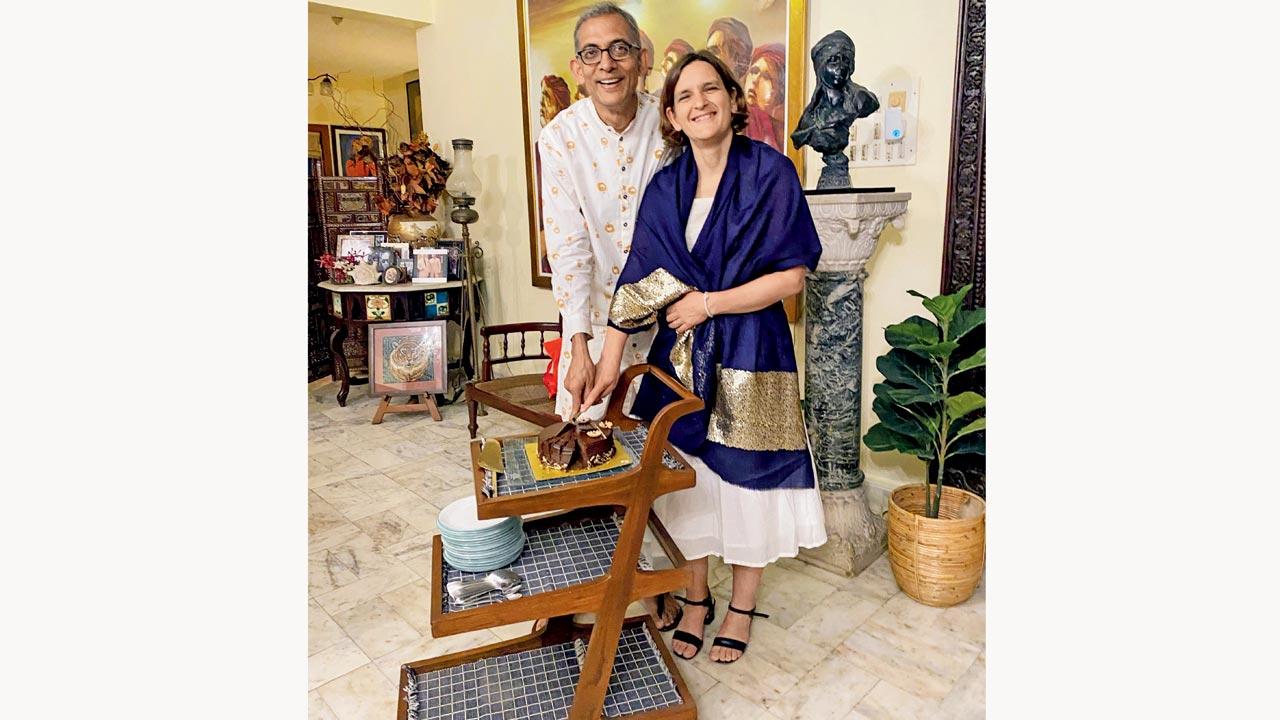

Nobel Laureates Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo cut a cake during a dinner hosted by De and her husband Dilip at their Mumbai home last year

Nobel Laureates Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo cut a cake during a dinner hosted by De and her husband Dilip at their Mumbai home last year

Food remains her continuous companion in these stories—a metaphor for a life well lived. “Food defines us in a very primal way, but we don’t acknowledge it enough. We sometimes undermine the value of a meal shared [with friends and family]… the enjoyment of food is the greatest sensual pleasure. If we diminish that, we are depriving ourselves. It caters to a very basic need, which is hunger. And I attach great value to it—hunger for ideas, experiences, for colour, life. Once you lose hunger, you become a dead-to-stimuli kind of person. No creative person can deaden themselves, unless it’s an affliction.”

In Insatiable, she talks about growing up in an “austere, frugal, typically Maharashtrian home in which snacking between meals was considered a superfluous, wasteful, self-indulgent ‘bad habit’”. “Children were expected to adhere to consuming milk and biscuits if famished, and perhaps neatly unpeel and eat a generally overripe and spotted banana from a bunch lying on top of the refrigerator, protected by a mesh cover to keep fruit flies away,” she writes. “But the frugality in my home never made me experience deprivation,” De clarifies to us now. “There is a huge difference between not having enough and not having excess.”

Shakuntala, her mother, whose name was later changed to Indira—just like De’s was from Anuradha—was a typical “middle-class Maharashtrian homemaker”. “Aai was a practical woman, and incredibly comfortable in her own skin. She started to cook at 18 when she was married, and continued to till 78, for her four restless and hungry children and a very fussy husband. My baba was a very critical man with a discerning palate, so aai could never get away with an indifferently cooked meal. Imagine being on test, day after day.”

De and her sisters were roped into cooking duties early. “We learnt with and from aai. I was given the duty of rolling chapatis... I can also fry the most perfect pomfret,” she boasts with a smile. “It wasn’t something she insisted we learn, but if you were in the kitchen with her, you’d naturally pick it up. My older sister, Mandakini, who is now 86, can still make puran poli and ukadiche modak the way aai did.”

“Mr De”, which is how she addresses her husband Dilip, is equally devoted to his food. And there are generous mentions of this in the memoir. Like the time, they had Nobel Laureates Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, and their children Mimi and Mimo over at their place, and Mr De cooked them the Bengali doi maach. “Mr De has cooked doi maach for 125 guests and I can confidently declare him a doi maach world champion,” she writes in the book. “He doesn’t even look at a snack casually. He is acutely invested in eating any meal, and he won’t eat a meal that doesn’t meet his standards. This can drive me up the wall,” she tells us, confessing that while she isn’t as persnickety, her husband has elevated her own tastes. What she most likes about Mr De is that he is a happy cook. “There are so many men who make such a production out of it [cooking]. They want people to be jumping around them, and applauding, and saying, ‘Oh! Well done’. He plans well. I believe that an angry cook can never serve appetising food… it’s always somehow unpalatable.”

And that’s where this book also wins. It comes peppered with life lessons from someone who has seen her share of highs and lows.

While De’s stories more often than not revolve around her foodie encounters—dining with her hard-nosed journalist friend Olga Tellis who is a vegetarian, shuns spicy food and eats early; the “pure theatre” like experience of watching artist MF Husain create the complex Bohri lasan kheema, layer by layer; or her tête-à-tête with Salman Rushdie during a dinner party organised by friends Adi and Parmeshwar Godrej—she also celebrates the everydayness of her life. Her solicitous house-help Pushpa, her hairdresser Nasreen, the feisty maalishwali Babita, their cook Anil, and muttonwala Ansariji are part of the large cast that make this memoir.

“My children [read the memoir and] are very jealous… they feel I’ve written more about Pushpa than them,” she jokes. “To be honest, the pandemic led to a great deal of introspection. Once we were coming out of it, and our helps started to return to our lives, we realised how much we had taken them for granted,” she says, adding, “They are family to me. The conversations I have with them, I place high value on, because there is common sense, honesty and candour. We are sharing like two equals, not thinking about hierarchy.”

She feels that the COVID-induced lockdowns gave her husband and her time to focus on “shedding” rather than “adding”, moving away from situations and people who added zero value to their lives. She talks candidly now about witnessing cracks in close and personal relationships, when she says, the changing political climate and polarisation has spared nobody. “It’s tough to lose friends,” says De, “but it also becomes essential after a point. You have just those many hours in a day. Some relationships are like a time bomb; if you hear it ticking, walk away… walk away before it explodes and destroys both parties involved. Maybe in retrospect, they will thank you for it.”

This year also marks five decades of her writing career. “Looking back, I never quantified my work or gave it too much emphasis. But now that I am here, yes, it feels great.” And she isn’t quitting anytime soon. “I never once thought about taking a break from writing. That would only generate stress. Why would I take a break from something that I look forward to every single day of my life? So long as you are in the game, you give it your 100 per cent. The day you cannot continue, you use the ‘R’ word—retirement. But retire from what… ideas? How is that even possible?”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!