Dance, music, and some dhol tasha—brave Mumbaikars and their caretakers are showing us that Parkinson’s is not a death sentence. If you hold the fort, and gather tools, you don’t just survive, but thrive

Over the last 25 years, the Nenes have learned how to live with Parkinson’s—Govind as the patient, and Geeta his caregiver. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Last week, as the World celebrated Parkinson’s Day, 67-year-old Borivli resident, Geeta Nene found herself reflecting on the journey she and her husband Govind have been on for more than two decades. The turn of the new millennium brought with it changes they hadn’t anticipated. Govind began complaining of tremors, aching limbs, and a heaviness in his body he couldn’t explain. Alarmed, they visited a doctor—only to be met with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We had no idea what Parkinson’s even was,” Geeta recalls. “It started with his legs shaking, then eventually, both his hands. It was painful to watch him struggle. But it is what it is. Over the last 25 years, we’ve both learned how to live with Parkinson’s—he as the patient, and me as his caregiver.”

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disorder that primarily affects the substantia nigra, the part of the brain responsible for producing dopamine. As dopamine levels deplete, the body begins to betray itself—manifesting as tremors, stiffness, slowed movement, balance issues, and an overall decline in motor function. But that’s just the beginning.

Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2021, Yogesh Ruparel continues to hold on to one of his most cherished traditions—playing the dhol during Gudi Padwa processions. Despite the challenges, he remains committed to this ritual. This year, he played the dhol non-stop for an hour!

Diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2021, Yogesh Ruparel continues to hold on to one of his most cherished traditions—playing the dhol during Gudi Padwa processions. Despite the challenges, he remains committed to this ritual. This year, he played the dhol non-stop for an hour!

Dr Maria Barretto, CEO of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society (PDMDS), explains that the diagnosis is only the first hurdle. “Most people are simply told, ‘It’s a chronic condition.’ That’s it. No one prepares them for what’s next.”

According to her, patients and their caregivers are left to navigate a minefield of confusion and more importantly, stigma.

Barretto, a psychologist who has been with PDMDS for over 20 years, was drawn to this work after realising how little awareness—and support—existed for those living with the disease. “Because of the fear of stigma, people often don’t talk about it,” she says. “This silence creates more confusion. Friends and even family members may not understand what’s happening—why someone is suddenly moving slowly, has a tremor, or is behaving differently.”

The Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society (PDSM) was built on the ethos of creating a space where people could meet others living with the same condition—not in a hospital, but in a community setting. Last week, patients of PD met at Our Lady of Salvation Church in Dadar to do movement exercises. Pics/Anurag Ahire

The Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society (PDSM) was built on the ethos of creating a space where people could meet others living with the same condition—not in a hospital, but in a community setting. Last week, patients of PD met at Our Lady of Salvation Church in Dadar to do movement exercises. Pics/Anurag Ahire

For 58-year-old Yogesh Ruparel, the silence was something he refused to accept. He first noticed a strange tremble in his toe in early 2021 while sitting in his living room in Worli—just as the second COVID-19 wave hit the city. “My father had Parkinson’s too, and at the time, he was bedridden,” he says. “So when I felt the tremor, my mind went straight to Parkinson’s.”

After six months of several consultations, and countless unanswered questions, the diagnosis was confirmed. Though he had anticipated the outcome, hearing it spoken aloud was devastating. “I entered a phase of denial. I had just lost my father to COVID three months before. Everything had collapsed.” Already dealing with Ankylosing Spondylitis, a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the spine, Ruparel felt like Parkinson’s was the final blow.

But then came a turning point. “One day, my son said to me, ‘Just accept it, Papa. We’ll work on this together.’” That moment, he says, snapped him out of despair. He began sharing his diagnosis openly, started physiotherapy, started going to the gym, and signed up for dance movement therapy. “I didn’t even know I could dance,” he laughs. “But the rhythm just took over. It was freeing.”

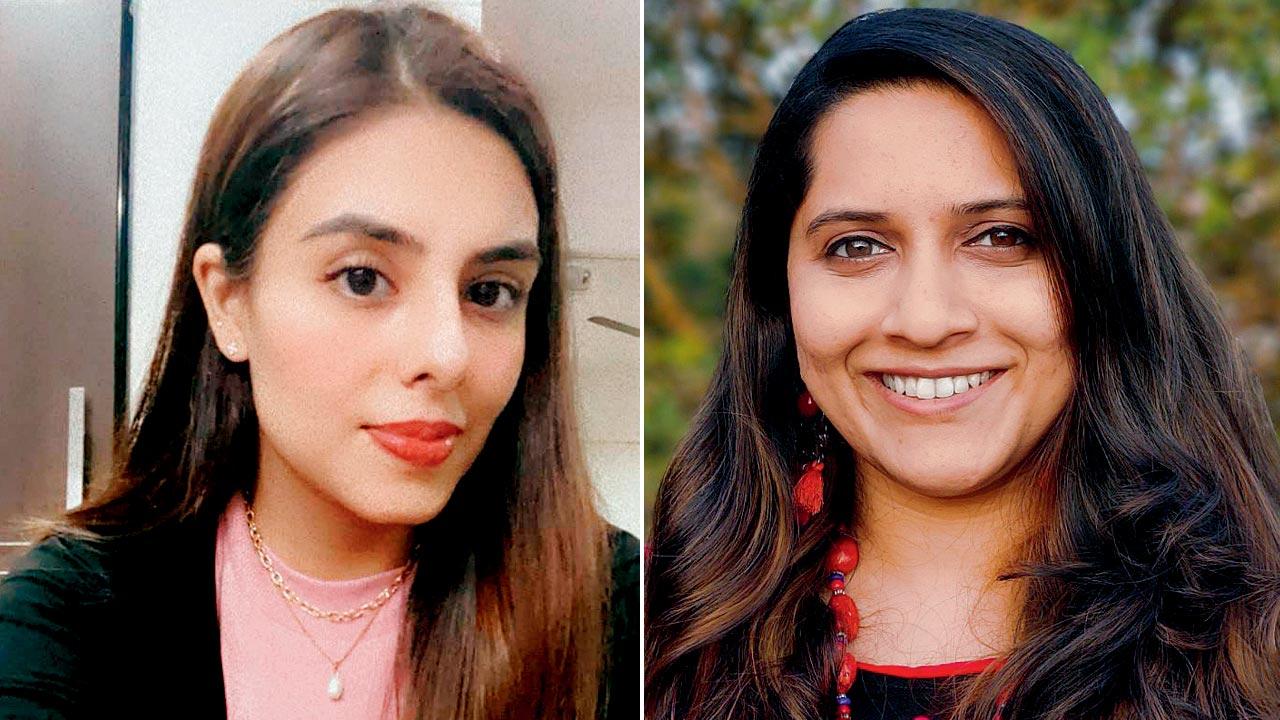

Dr Sakshi Lalwani and Tejali Kunte

Dr Sakshi Lalwani and Tejali Kunte

Dance Movement Therapy (DMT) has become a key tool in holistic Parkinson’s care. Tejali Kunte, a Clinical Psychologist and Dance Movement Therapy Facilitator, who has worked with many individuals with PD, explains: “The mind and body are deeply connected. With Parkinson’s, that link becomes even more critical. Anxiety worsens tremors; tremors increase anxiety. Movement helps regulate both.”

Unlike performance-based dance, DMT focuses on autonomy, expression, and presence. “We teach patients how to listen to their bodies, breathe through tremors, and recognise what their symptoms are telling them.”

This form of therapy is especially powerful given the range of non-motor symptoms that come with PD—many of which remain under reported. Depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, hallucinations, and even gastrointestinal issues are common. “Patients might not know their insomnia or constipation is related to Parkinson’s,” she adds. “This lack of awareness can further isolate them.”

Married for forty-four years, Geeta Nene and her husband Govind have been navigating Parkinson’s together for almost 25 years now—him as the patient, and her as his caregiver. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Married for forty-four years, Geeta Nene and her husband Govind have been navigating Parkinson’s together for almost 25 years now—him as the patient, and her as his caregiver. Pic/Anurag Ahire

“One of the things I felt very strongly about was creating a space where people could meet others living with the same condition—not in a hospital, but in a community setting, somewhere they felt comfortable and safe,” Barretto notes, while recalling the ethos of PDMDS. “Today, PDMDS has support centres across the country—from North to South India.”

According to Barretto these are not just casual meet-ups. Every session is structured and carefully designed, with activities ranging from speech and communication therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and even music and movement exercises. These interventions are all part of a multidisciplinary approach to care.

One of the traditions Ruparel holds closest is playing the dhol during Gudi Padwa processions—a ritual he’s preserved even after his diagnosis. “This year, I played the dhol continuously for an hour. It was truly riveting.”

Dr Maria Barretto

Dr Maria Barretto

Inspired by a conversation with his sister’s neighbour—a man who had shut his shop and social life after his diagnosis—Ruparel decided to form a peer support group. “That man told me, ‘My life ended the moment I was diagnosed.’ And I thought, that’s exactly why we need each other.”

Today, Ruparel facilitates virtual support circles with seven other patients. They meet online every few days where they share tips, offer support, sometimes just vent. “One thing I keep telling them is—you have to build an iron will. You have to want to be independent and work towards that,” he says. “So that you can eat your own food without messing up the table. Use the washroom without feeling embarrassed. So that you don’t have to be dependent on someone for your daily routine. It takes practice, and a strong will. But it’s possible. I’m living proof.”

According to the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, India is on track to have the largest population of Parkinson’s patients globally. The country sees 15 to 43 cases in every one lakh people, with up to 45 per cent of those diagnosed between the ages of 22 and 49.

And it’s not just motor skills that deteriorate. Vision, too, can decline. Dr Sakshi Lalwani, a neuro-ophthalmologist at CEDS Eye Hospital, explains that Parkinson’s can affect contrast, clarity, and peripheral vision over time. “In some patients, even eye movement is compromised. They may struggle to look up or down.” She emphasises the importance of early dopamine supplementation and environmental adjustments—better lighting, ergonomic setups, and of course, counselling. “Losing control over your vision can be psychologically taxing.”

Some cases are far more severe. Dr Ashok Patel, a Bandra resident, lost his brother to Parkinson’s Plus Syndrome in 2018. Unlike standard Parkinson’s, this rare variant is resistant to medication and far more aggressive. “He was bedridden for almost two years,” Patel recalls. “His body stopped working, but his mind stayed sharp. Even when he lost his speech, he could still understand everything.”

Another friend of his, a doctor himself, lived with Parkinson’s Plus for nearly a decade before passing away at 64. “It didn’t matter how disciplined or healthy he was—his condition just kept deteriorating.”

According to Parkinson’s Foundation, between 20 to 40 per cent of people with PD experience some form of psychosis—ranging from confusion to vivid hallucinations.

These non-motor symptoms can be just as debilitating as the physical ones, but they often go unnoticed, unspoken, and untreated.

Barretto recalls a session with one patient who told her, “I can see horses behind you.” It was a hallucination—a symptom often triggered by Parkinson’s-related changes in the brain. “These incidents show us just how complex the disease really is. It’s not just about movement—it’s about how people perceive the world, their bodies, and their place in it.”

And yet, through it all, people like Ruparel continue to find ways to move—“Maybe getting Parkinson’s wasn’t such a bad thing after all,” he says. “It taught me how to live healthier, explore things like dance and singing—and I’ve even seen an improvement in my Ankylosing Spondylitis because of it.”

20-40 %

People with Parkinson’s who suffer from psychosis—which ranges from confusion to vivid hallucinations

Source: Parkinson’s Foundation

15-43

out of every 1 lakh people in India are diagnosed with Parkinsons

45%

of those are diagnosed between the ages of 22 and 49

Source: International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!