While the city’s Anti-Terrorism Squad has been immortalised for fighting the notorious D-gang, the mission for which it was set up had its roots in the migration of Punjab’s worst nightmare—the Khalistan movement—to Mumbai

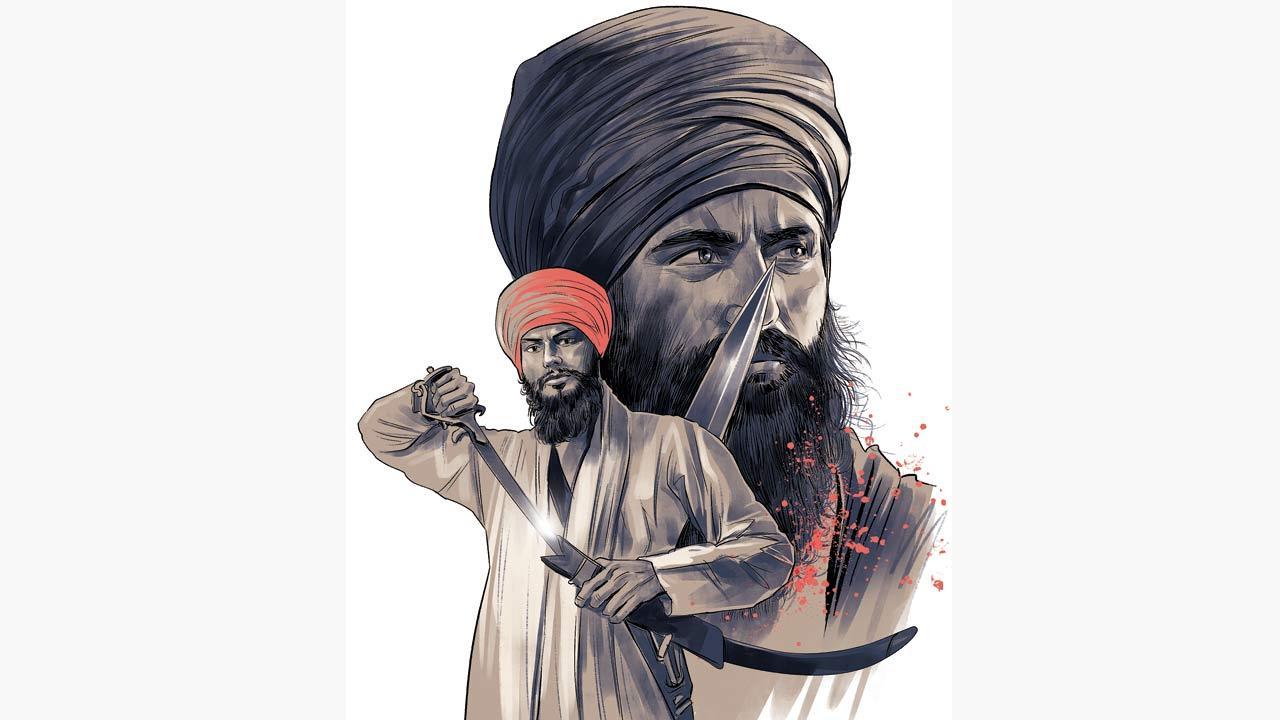

Illustration/Uday Mohite

As the hunt for Amritpal Singh, head of Waris Punjab De, intensifies with the Punjab police spreading their dragnet far beyond the state’s borders, a group of people in Mumbai are following the ongoing developments closely. With each new revelation about how Singh is managing to stay ahead of authorities, the tactics employed by him are bringing back haunting memories from 1989.

ADVERTISEMENT

On a December morning that year, Lakhmer Singh, a police sub-inspector with the Mumbai Traffic Police, was directing traffic at the Gandhi Nagar junction in Vikhroli when he saw a Gypsy idling at the traffic light, even though it had turned green. When he sent a constable to find out, the occupants of the jeep—four turbaned Sikhs with shawls draped over their shoulders, simply raised the shawls and showed the constable the AK 47 assault rifles underneath. The terrified constable ran back to report to Singh even as the Gypsy drove away. However, just as Lakhmer was making a frantic call to the control room, the vehicle returned. The four men stepped out, trained their guns and wordlessly shot the uniformed policeman down in broad daylight.

The result was the formation of the very first Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) in Maharashtra under the late IPS officer Aftab Ahmed Khan. Under his leadership, the ATS tracked Lakhmer’s killers all the way to Gujarat a month later and shot them dead in a 22-hour battle. The ATS went on to investigate and neutralise several Khalistanis in Mumbai post that, effectively wiping the menace off the face of India’s financial capital.

Alaisha Khan, daughter of the late Aftab Ahmed Khan who headed the first ATS, which cracked down on the Khalistani menace in Mumbai in the 1990s. The sustained crackdown made Khan and his family a target; Alisha too, narrowly escaped twice. Pic/Sameer Markande

Alaisha Khan, daughter of the late Aftab Ahmed Khan who headed the first ATS, which cracked down on the Khalistani menace in Mumbai in the 1990s. The sustained crackdown made Khan and his family a target; Alisha too, narrowly escaped twice. Pic/Sameer Markande

Retired ACP Shamrao Jedhe, among the senior-most in the squad after Khan, says that every tactic that Amritpal is using today is similar to the ones used by the Khalistanis in Mumbai back in the 1990s.

“Amritpal is obviously well trained in evading the law, as no one can outwit an entire police force without training and support. He has the capability to anticipate challenges and overcome them as soon as they appear. The frequent changing of vehicles, being constantly on the move and the help he is evidently getting from a large support base were all the characteristics of the Khalistanis that we were chasing back then,” says Jedhe.

He shares an interesting revelation that had come to light during their investigations. “The Khalistanis have a ready network of sleeper agents who are only given one task: be ready to shelter those on the run when the occasion demands. These agents won’t pick up a gun or make a provocative speech their entire lives, but when a Khalistani comes knocking, they know exactly what to do. Clothes, money and vehicles are quickly provided and shelter for the night is offered. The terrorist is gone the next morning.”

Shamrao Jedhe and Iqbal Sheikh, former ACP

Shamrao Jedhe and Iqbal Sheikh, former ACP

Lakhmer’s murder was only the latest in a string of examples of the ruthlessness of Khalistanis, who had moved to Mumbai from Punjab after Operation Bluestar. A few days before that incident, they had crushed an entire family of four, including two small children, under a tanker in Kalamboli because the head of the family refused to “contribute to the cause”.

“Mumbai was a green pasture,” recalls retired ACP Iqbal Sheikh, who was a sub-inspector, when he was drafted into the ATS. “Money was easy to get. A lot of Sikhs had settled in Mumbai when the Khalistani movement made life hell for the common man in Punjab. You couldn’t step out of your house after 5 pm in Punjab in those days, because death stalked the streets. The people came to Mumbai and set up hotels or transport businesses, and ended up becoming prime targets for extortion for the Khalistanis who followed.”

The Khalistan movement was at its peak in the 1980s, when Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale gave out a clarion call for a separate state of Khalistan and asked his followers to achieve this goal by any means necessary. Born Jarnail Singh, the political revolutionary added ‘Bhindranwale’ to his name after the village of Bhindran, where he attended a Sikh seminary and went on to become a wildly popular religious leader. The idea of Khalistan has its origins in the concept of a separate Sikh state that figured in the talks over the partition of Punjab in 1947, and by the 1970s, was responsible for the radicalisation of thousands of Sikhs.

In 1982, Bhindranwale moved into the Harmandir Sahib, popularly known as the Golden Temple, in Amritsar, stockpiling weapons and amassing soldiers for the cause. Finally, in June 1984, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian armed forces to storm the temple in what was famously codenamed Operation Bluestar. Bhindranwale was shot dead, but so were hundreds of others, and the sacred site for the Sikh community was damaged severely. The crackdown spurred an exodus out of Punjab. The Khalistanis who could go abroad did so, gathering support in countries like Canada and the United States of America. Others came to Mumbai.

Amritpal, who arrived in India last year from Dubai, had taken after Bhindranwale. His neatly trimmed hair and clean shaven face had been replaced by long hair tied in the traditional Sikh turban, a flowing beard and kada and kirpan worn by devout Sikhs. Just like his idol, he built up a massive follower base. In February this year, Amritpal and hundreds of his followers stormed the Anjala police station in Punjab armed with swords and guns to get their associate—Lovepreet Toofan—released. Toofan had been arrested in a kidnapping and assault case and at least 20 policemen were injured before the assault was staved off.

“If the leader is charismatic enough, the followers are ready to lay down their lives. The way Amritpal’s followers have been running interference to keep him out of the police’ clutches, we saw the exact same thing back when we were hunting wanted terrorists like Baldev Singh,” Sheikh says.

Baldev Singh, the head of the group that shot down Lakhmer, was among the first Khalistanis on the ATS’ radar.

The near day-long encounter that began on January 24, 1990, in Vadodara, and which resulted in the deaths of Baldev and his three accomplices, was planned with surgical precision. “Civilian vehicles were arranged for, the quickest routes to Gujarat were identified so that the squad could get there fast, and complete secrecy was maintained. The result was a massive boost in morale for police and civilian alike,” recalls Jedhe. The police control rooms in Vadodara as well as Mumbai had relayed every detail of the ongoing encounter live and by the next morning, the entire country was talking about it.

Over the next two years, the ATS went hammer and tongs after the Khalistanis. Among their chief victories was the arrest of four Khalistanis who had come to Mumbai to kidnap the grand-niece of former Indian Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao. She was supposed to be the leverage to negotiate the release of the killers of General AS Vaidya, who had headed Operation Bluestar.

Another huge feather in their cap was when they nabbed Manjeet Singh alias Lal Singh, wanted for the twin bombings of two Air India flights in 1985, at the Dadar railway station in 1992. Manjeet’s arrest for the first time confirmed the fact that the Inter Service Intelligence (ISI), Pakistan’s premier intelligence agency, was providing support to the Khalistan movement, another common factor between then and now.

Indian intelligence agencies have confirmed that Amritpal has been getting massive support in terms of funding from the ISI. Back then, the ATS had discovered that the ISI had provided shelter to Manjeet and given him a whole new identity before sending him back to India with new mission objectives.

“Manjeet was frighteningly committed to the cause. After his arrest, we were interrogating him night and day and at one point, he realised he would not be able to resist much longer. At that point, even as I was interrogating him, he looked me in the eye and bit his tongue off with his own teeth. I can still hear that sickening crunch,” Jedhe remembers.

For Jedhe, the revelation of Amritpal’s ISI link was anything but surprising.

“The ISI and the Khalistan movement have been in bed with each other for decades. Manjeet’s arrest was just a confirmation, but we have always known that they are inter-dependent on each other for the common goal of causing disruption in India,” he says.

The ATS’ crackdown, however, was not without consequences. Particularly Khan, who became the face of the anti-Khalistan action in Mumbai, constantly had a target painted not just on his back, but also his family. Khan’s daughter Alaisha recalls how she came close to being kidnapped when she was six years old. “I was studying in a school in Vashi and dad’s official vehicle, with a police driver used to pick me up. On that day, there was a new driver I had never seen before. Nothing about him, from his accent to his appearance, was like any policeman I was familiar with. My suspicion changed to certainty the minute he turned in the opposite direction, taking me to Turbhe instead of our Thane residence. I rolled down the window and started shouting, and a couple on a motorcycle, who were going in the opposite direction, turned around and started following us. The driver stopped right there and fled,” Alaisha shares.

After the incident, Khan sent Alaisha to a boarding school in Panchgani and rented a bungalow close to the school for her mother to stay, so that someone could be close to her. When she was 11, her mother took her to Mumbai for the holidays; they returned to Panchgani some days later. The plan was to stay at the bungalow and go back to school the next morning.

“When we reached the bungalow, the electricity was out and the phones were down. We went to ask the owner, who stayed in another bungalow nearby. The owner’s aged mother, who was alone in the house, started wailing as soon as she saw us. Between sobs, she managed to tell us that men armed with ‘big guns’ had come to our bungalow the previous day and cut the power and phone lines. Dad sent a team to get us, and we sped back to Mumbai immediately,” Alaisha says, still uncomfortable with the memory. As Jedhe simply puts it, “It was war.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!