The recent decision to drop the organ from use in devotional Sikh music, means the instrument of French origin must once again justify its place in music of the subcontinent

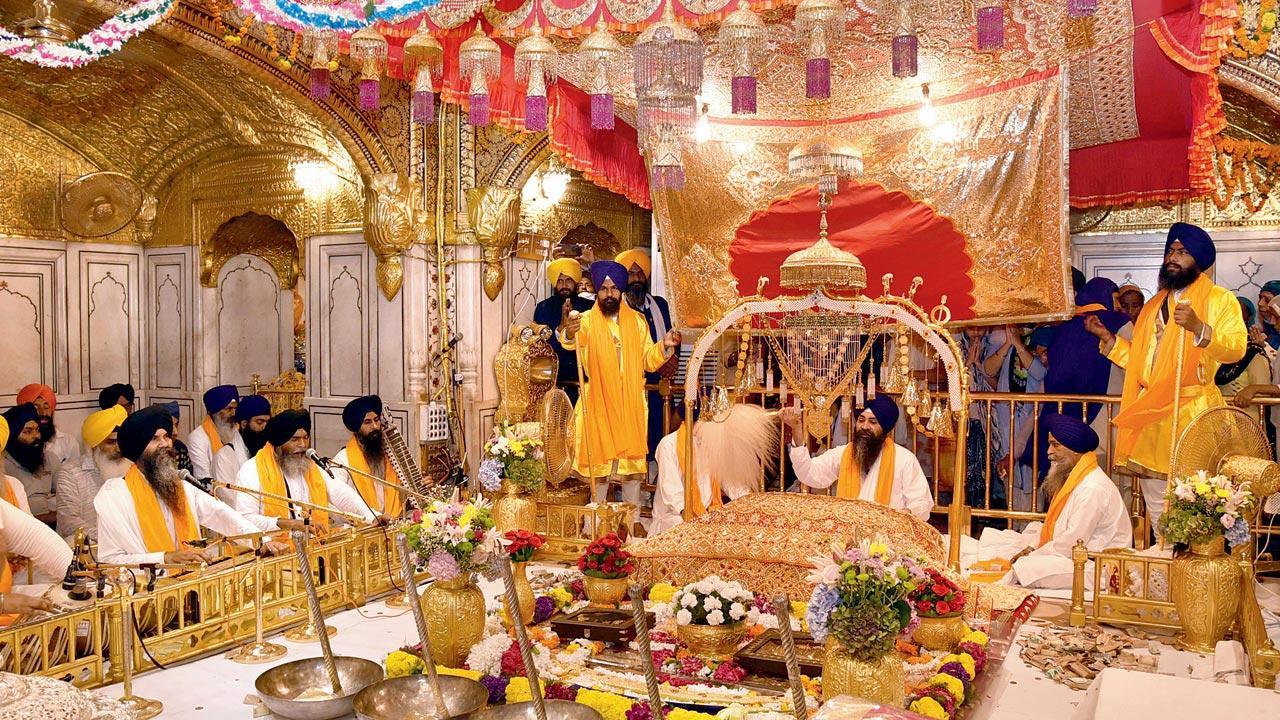

While the Akal Takht wants the harmonium banished from the Golden Temple and replaced with traditional kirtan string instruments, the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee feels this is easier said than done. Pic/Getty Images

When the music for Ashutosh Gowarikar’s Jodha Akbar was launched, this writer wondered why Madras Mozart AR Rahman had opened the first track, Khwaja mere khwaja with bars of the harmonium; he could’ve used any instrument in the world he fancied.

ADVERTISEMENT

The harmonium was invented and patented by Alexandre Debain of France way back in the 1840s. A staple in church music, far larger and heavier than we know it today. Multiple interventions over the years made it more compact, allowing it to enter homes in India during the colonial rule. Back then, it had foot-operated bellows unlike the ones you see now at the rear of the instrument. It became popular in India and in Indian classical music only after musician Dwarkanath Ghose, who ran an instrument manufacturing unit, created a smaller version in 1875 with the hand-operated bellows and the addition of drone knobs that would help produce Indian classical harmonies.

Gwalior gharana doyenne Neela Bhagwat, who prefers the accompaniment of sarangi over the harmonium, when singing, says, “Though closest to the human voice, the sarangi needs a minimum of eight to 10 years of dedicated training for basic proficiency. Compare this to the harmonium which you can learn the basic in a few days.” Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Gwalior gharana doyenne Neela Bhagwat, who prefers the accompaniment of sarangi over the harmonium, when singing, says, “Though closest to the human voice, the sarangi needs a minimum of eight to 10 years of dedicated training for basic proficiency. Compare this to the harmonium which you can learn the basic in a few days.” Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

In the atmosphere today, when the “outsider” is the enemy, whether Mughal or British, it came as little surprise that the harmonium, identified as not traditionally Indian, would be on drop list from instruments played at the Golden Temple.

The gurudwara in Amritsar, considered the pre-eminent spiritual site of Sikhism, has a group of hymn singers called ragi jathas singing 31 ragas over 20 hours daily as veneration to the place. The music is seen as an appreciation of the holy books of the Sikhs, the Adi Granth.

Giani Harpreet Singh, the jathedar or ordained leader of the Akal Takht or Sikhism’s highest theological body, last week ordered the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) to replace the harmonium—an instrument with colonial roots—with traditional string instruments. He said that tanti saaz (string instruments) such as the taus, dilruba, rabab, dhad, and sarangi accompanied Sikhism founder Guru Nanak, and not the harmonium.

Harmonium exponent Sudhir Nayak explains that unlike harmony-based Western music, Indian music is more melody-based

Harmonium exponent Sudhir Nayak explains that unlike harmony-based Western music, Indian music is more melody-based

When the hazuri raagis (hymn singers who also play instruments) expressed concern over the move, SGPC chief Harjinder Singh Dhami agreed that efforts will be made to revive the tradition of stringed kirtan instruments but in a phased manner. “Till then, the existing harmonium accompaniment to the kirtan recitation, that has been going on for over a century, will continue. After three years, even if we reintroduce tanti saaz fully, I don’t see the harmonium going away. It’ll continue to be played alongside,” he insisted while speaking to Sunday mid-day.

Although limited to one community, the news ignited a debate over the use of the harmonium among classical musicians and performers of the subcontinent where genres such as folk, devotional, and the ever-popular film music have seen the Western harmonium firmly ensconce itself with its accompanying omnipresence.

“Musicians in north India took to it immediately as the hand pump version helped them perform while sitting on the floor,” points out harmonium exponent Sudhir Nayak. “It was able to shadow or mimic vocalisations of the singer and could steady the flow of the composition. It was easier to learn, tune and play, compared to the tanpura and sarangi. Unlike harmony-based Western music, Indian music is more melody-based and playing with one hand was adequate.”

Qawwals at the shrine of Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi. The harmonium became the principal, and the sole, instrument for qawwali. Gradually, it developed a reputation as an instrument for devotional music in four traditions. Pic/Getty Images

Qawwals at the shrine of Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi. The harmonium became the principal, and the sole, instrument for qawwali. Gradually, it developed a reputation as an instrument for devotional music in four traditions. Pic/Getty Images

This isn’t quite the first time that the instrument has been at the centre of debate. When the Swadeshi movement sparked by the Partition of Bengal in 1905 propagated the idea of aggressively rejecting all things British, the harmonium (although it came from continental Europe and not Britain) became an unfortunate target, despite the fact that the version being used then was the one that has been adapted by an Indian.

Before its arrival, most Hindustani vocalists sang to the accompaniment of the sarangi, a bowed, short-necked string instrument, says Gwalior gharana doyenne Neela Bhagwat, who prefers to use it while performing. “Though closest to the human voice, the sarangi needs a minimum of eight to 10 years of dedicated training for the most basic proficiency. Compare this to the harmonium who’s basics you can learn within a few days,” she says, adding, “No wonder that the harmonium began to replace the sarangi as an accompaniment to vocalists.”

Explaining the limitations of the harmonium, she says that while Indian music’s idea of 12 notes in an octave is nearly the same as in Western music, there are significant differences. The Indian note in an octave does not correspond to a specific pitch point, but to a pitch range with multiple nuances. “No keyboard instrument can do this,” she says, “it can only play one note or the next. The harmonium too can’t generate the meend [glide from one note to another] like the sitar or veena. It was felt that sound ornamentations and trills, which are the hallmark of Indian classical music, couldn’t be played effectively on the harmonium.”

This gave more power to the anti-harmonium brigade. All India Radio, then India’s monopoly radio broadcaster, banned the harmonium from 1940 to 1971. Since then, it is allowed in the broadcast of orchestral music, but a solo harmonium recital on AIR is still scoffed at.

Incidentally, although Rabindranath Tagore had taken a great liking to the instrument which he used to compose several songs, the Nobel laureate later not only tired of its musical limitations but forbade its use in Shantiniketan.

Legendary vocalists Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Begum Akhtar, and Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, however, used the harmonium to accompany them while singing. “It had a rich, continuous tone that only a sarangi-player or violinist with a steady hand and immaculate bow control could match,” says Bhagwat.

Apart from being easy to pick-up, the harmonium was excellent for group singing, loud enough for the drone to fill a concert hall, and hence it is still the key instrument in teaching students the rudiments of music and song. Hindu and Sikh groups quickly adopted it for their devotional music (bhajan, kirtan, dhun, shabad), using a tabla or dholak for percussion, along with bells and cymbals.

Christians didn’t lag behind; they used it to sing hymns in Indian languages. The harmonium became the principal, and often the sole, instrument for qawwali, a devotional music tradition of Sufism that goes back seven centuries. The instrument had now justifiably developed a reputation as an accompaniment for devotional music in four religious traditions in the subcontinent. Carnatic music did not warm up to it as much as it did to the violin (another Western import) which came later, but for exceptions such as Perur Subramanya Dikshitar or Palladam Venkataramana Rao, who used it.

Naysayers notwithstanding, the harmonium became popular with the fillip that Hindi film songs gave it. The abiding popularity of Leke pehla pehla pyaar from CID (1956), Bahut shukriya, badi meharbani from Ek Musafir Ek Haseena (1962), Kajra mohabbat wala from Kismat (1968) by OP Nayyar; Chalat musafir from Teesri Kasam (1966) by Shankar-Jaikishan; Na toh carvaan ki from Barsat Ki Raat (1960), Nigahe milane from Dil Hi To Hai (1963) by Roshan; Saaqiya aaj mohe from Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962) by Hemant Kumar, Payal ki jhankar from Mere Lal (1966) and Chunari sambhal from Baharon Ke Sapne (1967), Ek chatur naar from Padosan (1968), Hai agar dushman from Hum Kise Se Kam Nahin (1977) by RD Burman is proof.

1875

The year in which Dwarkanath Ghose designed the Indian hand-pumped version of the harmonium in Kolkata

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!