A smartly organised art fair that debuted in Mumbai, and a 25-year-old annual film festival that returned last month, had prohibitively priced tickets. Do entry fees to high-art events and cinema soirees, put them out of reach for the common appreciator?

A glimpse from the first edition of Art Mumbai, the city’s first art fair which attracted 15,000 attendees. Pic/Art Mumbai

Is viewing art only the hobby of the wealthy? We couldn’t help but wonder after noticing the pattern of hefty ticket prices for the slew of events mushrooming over the cityscape. Or have we been so spoiled by Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum (R10/adults, R5/kids) and Jehangir Art Gallery’s (free) pyaar that we baulk at the thought of reaching into our wallets for a cultural education?

ADVERTISEMENT

For instance, Art Mumbai 2023, the first-of-its-kind event held in November, had an entry price of R1,500 for the day, and R2,500 for three-day pass. More than 53

galleries collaborated to bring together the works of over 300 artists in a honeycomb of booths in tents at Mahalaxmi Racecourse, and it was englamoured by the presence of rare Raja Ravi Varmas and MF Husains.

Still. Consider this: In the 2000s, you could attend screenings by The Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) at premium theatres such as INOX on a shoe-string budget; or for free as a student. Granted those were the early years (the festival commenced in 1997), this year required an enthusiast to shell out R1,500 to watch three movies a day.

Bollywood actors Rajkummar Rao and Patralekha pose upon their arrival for the opening ceremony of ‘Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival 2023’ in Mumbai on October 27. Pic/Getty Images

Bollywood actors Rajkummar Rao and Patralekha pose upon their arrival for the opening ceremony of ‘Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival 2023’ in Mumbai on October 27. Pic/Getty Images

Doesn’t this immediately keep art out of the common person’s reach? Is that the intent? Or is it just the realistic cost of production for air-conditioned marquees, security for priceless pieces and maintaining the life of vintage, gold-spun zari on a 300-year-old Paithani saree?

The Kala Ghoda Arts Festival (KGAF), founded in 1999, steadfastly stands as one of the oldest free public events in the city to remain so. All its offerings—music concerts, dance recitals, theatre—come free of a tag, year after year. How?

“Everybody wonders how we manage without charging the public,” laughs Brinda Miller, KGAF’s chairperson, “Funding is a big challenge and we scramble for it all through the year. However, we received a lot of love post COVID, even when [corporate] funds for such events were drying up.” Over the years, publishing groups have played main sponsor for KGAF, their name prefixed to the festival. In the case of smaller sponsors, representation is only through art. “For example, a chocolate company may want an installation featuring their product,” says Miller, “But we do it organically. No banners or posters… it’s just not what Kala Ghoda stands for.” Funds also trickle on goodwill earned over the years. “Many philanthropists come forward to help us because they know what we are doing for the city. We give space to all kinds of artists—veterans, students, and even those who have never studied art. But we never offer them funding; we just cannot.”

Alisha Sadkote, Ranjit Hoskote and Arjun Bahl

Alisha Sadkote, Ranjit Hoskote and Arjun Bahl

Does the quality (and fame) of the artists hosted justify the entry ticket price of mega events then? “I do not think so,” says Miller, over the phone, “Many established artists showcase their work at festivals such as ours because they want a wider audience and also it is their way to give back [to society].”

The line she draws is between a cultural festival for the city, and a marketing exercise for their product—the artistic works—by a curator, artist or gallerist. “I understand why these events take place; the artist has to make some money,” she says. “I do Kala Ghoda out of passion, but for the rest of the year I do make [art] for a living. But accessibility to view such art is important as well; festivals such as KGAF play that important role.” This year, KGAF will be held from January 20 to 29. "An entry fee only works for museums,” informs Ayesha Parikh, the founder of Bandra’s Art and Charlie. Funding for them can come from multiple sources such as state and central governments, private philanthropists, philanthropic trusts, other museums, as well as CSR wings of corporations.

The Sassoon Dock Art Project drew three lakh visitors in 2023. File pic

The Sassoon Dock Art Project drew three lakh visitors in 2023. File pic

Even the early success of film festivals such as MAMI was bolstered, in part, by government funding. “Many other festivals in the city also had funding from the government, so you could register, take a pass and attend the festival for how ever many days it was being held,” says filmmaker Paromita Vohra, whose work has been showcased at the festivals such as MAMI and the Mumbai International Film Festival. Attending these allowed her, and many others, to learn the art of film making. “When these events were free,” she says, “I would go and sit there from morning till night, and it is from here that many a filmmaker emerged. Ticketing automatically limits the crowd and also the appetite of the audience who might [otherwise] love to see movies from different genres.”

When we reached out, JIO MAMI responded in a statement, “We are not a ticketed event. We encourage our delegates to register for the festival and as a part of that they get access to all audience facing programmes at the festival, Jio MAMI merchandise and free entry for all films across all venues. To a lot of institutions, especially students, we offer free registrations.” The phenomenon of paid registrations for film festivals is a worldwide practice and exists for many reasons, Jio MAMI’s statement says, “It helps in crowd management, gives an idea about what the occupancy will be like at each venue. Accordingly we prepare for the event.

There are multiple points involved in getting a film festival to audiences and it’s very important the organisers have a clear views on the expected number of people at each venue.

All around the world, city film festivals are ticketed .i.e. you pay to watch each film. At Jio MAMI, it’s a pass for 10 days of the festival with free access to all films, masterclasses, panels etc.”

The Kala Ghoda Art Festival last held in February 2023, began in 1999. File pic

The Kala Ghoda Art Festival last held in February 2023, began in 1999. File pic

“You have to realise that for galleries, art is finally a business,” says Parikh bluntly. “My approach to accessibility in art is slightly different: When we talk about lower prices for events, the key is [to strike] a balance. If you charge R200 for a ticket, it will take 20 visitors to make just R6,000— then the artist has no value, and that’s not nice. You are also not incentivising them,” she adds.

Parikh’s personal opinion is that people are too used to accessing culture at very low prices. “Private institutions can’t do that,” she says, “Funds can [only] be raised for places such as Prithvi Theatre. If people are willing to pay more, bigger artists can perform or be invited, and private institutions can hold more

such offerings.”

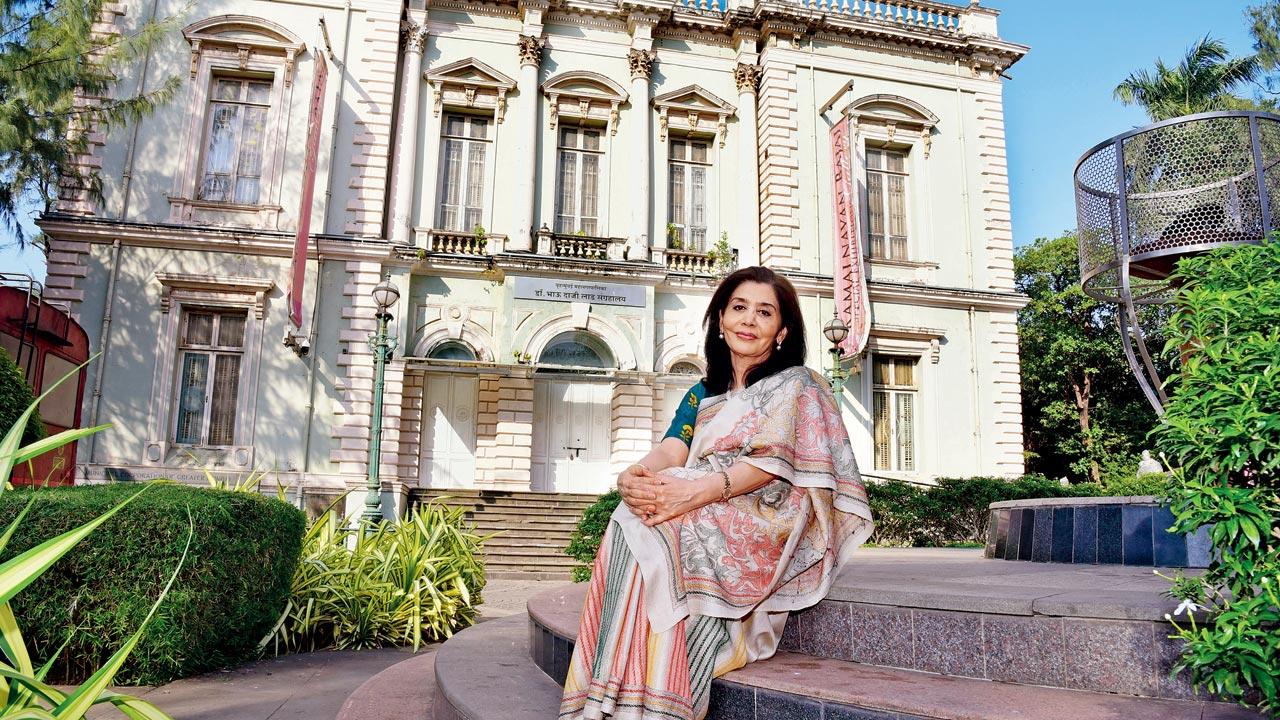

Tasneem Zakaria Mehta puts her weight behind this balancing act, stressing it is essential for the city’s art scene. “If you are looking for great art, one must understand what great art entails,” says the director of Byculla’s Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum (BDL), the city’s oldest art and antiquities archive, “To understand that something is of a certain calibre, one needs the exposure to understand it. For which you have to make a little bit of an effort to find out what’s going on, just like everything in life. At BDL, we do programmes on a massive scale for children. When we reopen—hopefully in a few months—the exhibits will be contemporary and modern; and our tickets are priced at R10, which means people of all economic backgrounds get a chance to come and view art here.”

Tasneem Mehta, director of BDL Museum, is working towards a grand reopening of the institution. Pic/Shadab Khan

Tasneem Mehta, director of BDL Museum, is working towards a grand reopening of the institution. Pic/Shadab Khan

Mehta understands that festivals and fairs command a high entry price since the displays and exhibits need protection, “but the fact is that the general population wants to be a part of these contemporary art exhibitions too. So, it’s a balancing act for the art world.”

The Sassoon Dock Art Project by the St+art India Foundation is among the events with the biggest footfall in the city. Co-founder Arjun Bahl pegs the number of visitors at the last edition, held from December 2022 to January 2023, to three lakhs. “One of the reasons we hosted the festival at Sassoon Dock is that the space in itself is so Mumbai. The sea, the fish, and ambience are so emblematic of the city; a corporate affair would never do,” he says of the event held at the city’s oldest and largest functioning wholesale fish market.

Roping in Mumbai Port Trust and Asian Paints as the project’s main sponsors across many editions has allowed the organisers to keep entry free. “We are not here to profit out of the event,” says Bahl, “Of course, priced tickets might help us to set up better facilities. [So] even if we introduce tickets, the fee will be R10 or R50, ensuring that people from all socio-economic arenas can experience art while standing next to each other—which is the way art should be experienced, without social boundaries. Everyone deserves to see art and have an opinion about it, and we hope that the ethos of the Sassoon Dock Art Project lives on beyond what we do.”

Brinda Miller the chairperson of the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival believes that there is no difference in the quality of art made available at ticketed and free festivals. Pic/Shadab Khan

Brinda Miller the chairperson of the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival believes that there is no difference in the quality of art made available at ticketed and free festivals. Pic/Shadab Khan

One way to gain an artistic education at low cost is through guided art walks, conducted by enthusiasts, educators or sometimes an artist themselves, for free or for as low as R500. Many of them are held in the city’s art pockets in Bandra, Flora Fountain, Colaba, Kala Ghoda, Khotachiwadi and even Worli. Such as the ones by Alisha Sadikot and Nishita Zachariah of Art & Wonderment, which democratise the seemingly bourgeoise interest.

Many of their patrons have held an interest in art, but never dared venture close to a gallery. “We accompany and guide people,” says Sadikot, “it’s like going to see art with friends, just that you don’t have to walk up to a gallery on your own and ring the bell.” The guided tours are usually held on Saturday mornings and priced at Rs 1,000 for adults.

“We are art historians,” she says, “We try to de-mystify what the artist is trying to say or the gallerist or curator—in ways that are engaging, encourage close looking and convey what we love most about the art we’re seeing. We also understand that it can be confusing to find galleries, or have information about exhibits. People tell us that they love the fact that we curate the route and show diverse art, and even find artists who let us peek into their studio and understand their process. What we find wonderful is that many of our guests become regulars at art galleries, even coming back and joining us for dates, family visits, and birthdays.” Sadikot says art walks have really taken off in the last two-years, after COVID-imposed restrictions were lifted.

Ranjit Hoskote believes that all art is easily available to everyone, at least in theory. “It may seem like a big transition in accessibility because until the early 90s, there were [only] three or four galleries in the city, and today there are quite a few, but they are all free for anyone to walk into,” says the poet, art curator, and art critic, who curated one of the first art shows at Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC). “Ticketed events such as the Mumbai Art Fair are annual occurrences, so they are not the rule but the exception.” The issue, says Hoskote, is that the coverage these events receive is not as good as the everyday, almost humdrum life of the art world that lives in its galleries. “People do not pay enough attention to the art found in free or modestly-priced art galleries, and even to exhibitions like the ones held at DD Neroy Gallery [Grant Road],” he says.

Hoskote believes that the marriage of new art centers such as the NMACCS to art fairs, festivals and smaller galleries will shape the ecosystem over the next 10 years, and shift the scene from south Mumbai to the suburbs.

Inputs by Neerja Deodhar

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!