The Ghiblification trend has once again sparked a debate over AI-generated art, but it has also brought joy to many who were unaware of the Japanese studio’s legacy

Singer-songwriter Siddhant Goenka uses AI to design music videos and album artwork; (right) Filmmaker and AI artist Varun Gupta uses AI to draw up retro-futuristic dreamscapes, comic strips, entire worlds, including this reimagined version of Mumbai, and a floating city. Pic/Varun Gupta

Lately, the Internet seems to have transformed into a Ghibli universe. People across platforms are sharing dreamy, AI-generated portraits of themselves in the unmistakable style of the Japanese animation house, Studio Ghibli.

But as with most viral AI trends, the reactions have been mixed. For some, this was a delightful moment of Internet whimsy. For others, it is a degradation of the legacy of Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, who had once said that AI-generated animation was an “insult to life itself”. But this time, there was a third response: Joy.

Most who have taken to the trend of sharing “Ghibli-fied” portraits have no idea who Miyazaki is; they may not have watched his iconic films, such as Spirited Away or My Neighbor Totoro. For them, the trend is not about his legacy; it’s about seeing themselves in art.

A still from Spirited Away, a film by Studio Ghibli, known for creating whimsical worlds meticulous hand-drawn, frame by frame. Pic Courtesy/Studio Ghibli

A still from Spirited Away, a film by Studio Ghibli, known for creating whimsical worlds meticulous hand-drawn, frame by frame. Pic Courtesy/Studio Ghibli

Balram Vishwakarma, who runs the Instagram page Andheri West Shit Posting, shared a story about his cousin who repairs trucks in Bihar. The cousin sent Vishwakarma a photo of his wife, asking him to turn it into a Ghibli-fied portrait. That evening, the wife called, breathless with excitement, saying she had never looked so magical. “It felt like the first time she saw herself as someone worthy of beauty,” Vishwakarma wrote on Instagram, “It wasn’t about anime, it was about access to a kind of softness usually reserved for a certain kind of person. The image may have been fake, but the emotion was real.”

The trend has undoubtedly brought people closer to a world they may never have accessed otherwise. In India, where exposure to art is still shaped by class, geography and language, the fine art world—and its ethical concerns over AI-generated images—has largely been limited to the elite. Until now, that is.

Writer, designer, and art researcher Prachi Popat has watched the Ghibli trend with curiosity and discomfort. “What I’m against is people calling these AI-generated images art. It’s concept design, not art,” she says and proceeds to question, “Is it the AI that’s generating the work or the person who is putting in the prompt? The role of the artist and the authorship of the artist gets a little blurry.”

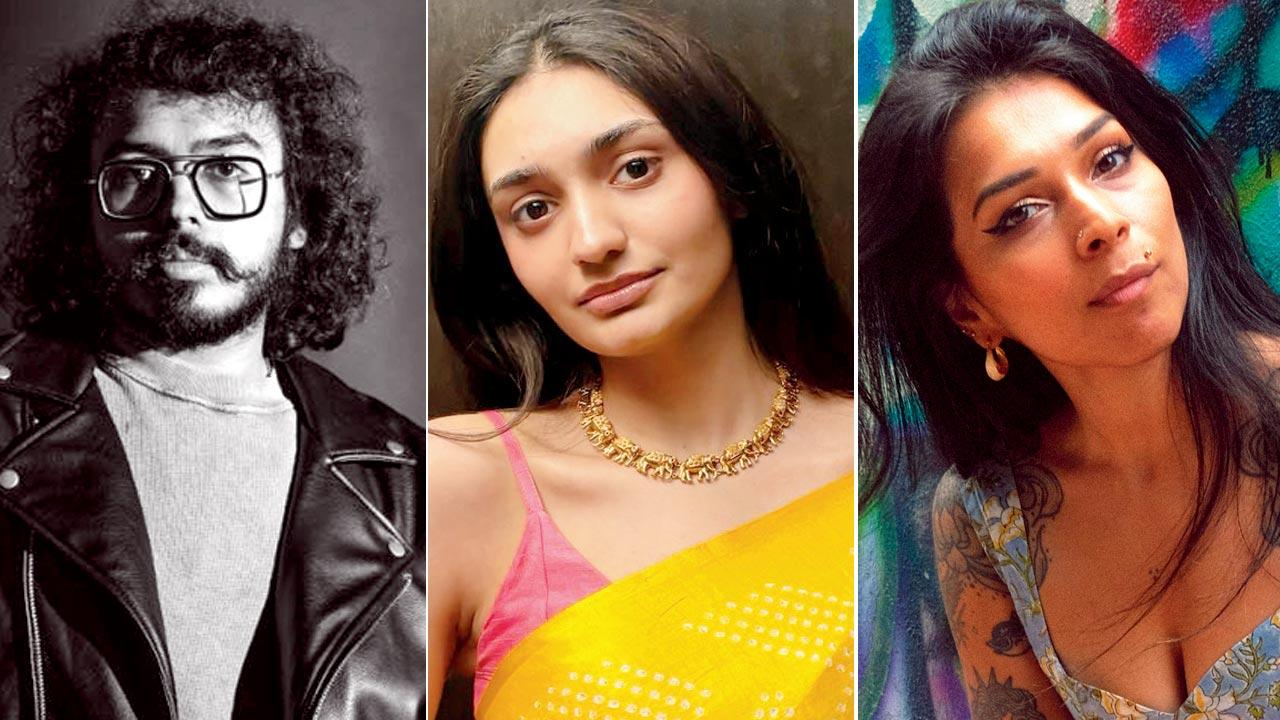

Siddhant Goenka, Prachi Popat and Namaah Kumar

Siddhant Goenka, Prachi Popat and Namaah Kumar

Namaah Kumar, a creative director and visual artist, counters that art has always been a collaborative medium. As a designer, she says, she should be threatened by AI, but it has created jobs for her as well. She has been asked to train teams and consult with them on using AI.

But does the fact that anyone can use AI to generate images mean that AI is helping democratise art? Popat makes an important distinction—AI democratises skill, not art. “Artists have spent years honing their craft. That labour is now replaced by a machine doing it in seconds. It’s not the same.”

She points out the overlooked role of auction houses in the conversation, calling Christie’s recent auction of AI-generated work “mind-boggling.” She sees it as a desperate move by traditional gatekeepers to stay relevant.

Srishti Guptaroy, Debopom Chakraborty and Rohan Dahotre

Srishti Guptaroy, Debopom Chakraborty and Rohan Dahotre

Wildlife illustrator Rohan Dahotre shares similar reservations. “I like the imperfections of an artist. This identity of the artist cannot be replicated. Art is more of an emotion,” he says.

Illustrator and visual artist Srishti Guptaroy says that AI has a lot of baseline use. “It’s a great tool when you have to present a render or a mockup to a client,” she adds, admitting, however, that anything generated by AI will not be art until there is human intervention.

For some creators, the draw is AI’s accessibility. Singer-songwriter Siddhant Goenka uses it to design music videos and album art, but draws the line when it comes to songwriting. “Using it for lyrics and composition just takes out the art,” he says. But for an independent artist like him, AI proves to be a more economical way to create music videos.

Varun Gupta, a filmmaker and AI artist, has been a long-time experimenter with AI tools. “Growing up, I had ideas but no access to tools. I couldn’t draw like my friends. Today, AI lets me express what I always imagined,” says Gupta, who uses AI to draw up retro-futuristic dreamscapes, comic strips, entire worlds.

Gupta admits that he struggles with the ethics of AI. To rid himself of the guilt, he trained Midjourney for over two years to produce art that reflects his imagination. “I have no problem with rules. Add them,” he says, adding that it will only help artists produce work without any guilt.

Debopom Chakraborty, a creative technologist and animator, predicts that while AI may not fully democratise art, it will make creation accessible and quick. “We will still write the story, design the characters, and produce the film. But the post-production phase is where AI will help,” he says. Fresh art graduates face the biggest risk of being replaced, he says, “as AI can take care of the grunt work”.

AI-generated art is here to stay. “Everyone is experimenting with it. I am making videos, and someone else is making ads,” says singer Goenka. “The only question now is, who is going to sustain creativity?”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!