Taking pointers from recent release, Maharaj, wend your way through the streets of SoBo to catch marvels of 19th-century Bombay that shaped the city’s cultural and political landscape

Gokuldas Tejpal Hospital

We don’t ever need a reason to explore the heritage of this city, but we have one with the recent release of period drama Maharaj, which while academics argue has not captured historical facts accurately, is still inspiration to explore the memories of Bombay of the 1800s. Centred around the life of social reformer and journalist Karsandas Mulji, the film portrays figures who contributed to the city’s infrastructure, institutions and shaped its social and political fabric. Use our guide for pointers, strap on your walking shoes and get set on this trail.

ADVERTISEMENT

Gokuldas Tejpal Hospital, Marine Lines

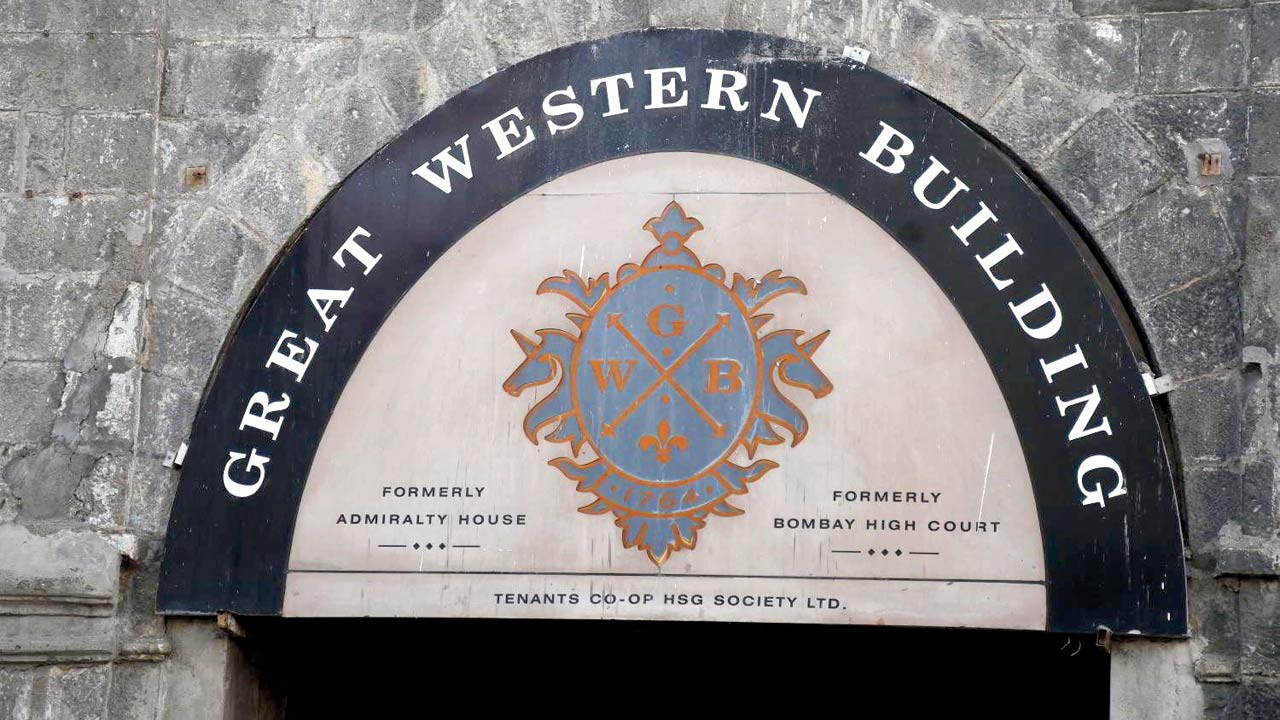

The Great Western Building, opposite the naval dockyard. PICS/ASHISH RAJE

Merchant and philanthropist Gokuldas Tejpal is believed to have stood by Karsandas Mulji during his legal travails according to the film. Tejpal passed away early at 45, leaving behind funds to run charitable institutions, including a boarding school. One of the institutions named after him is Gokuldas Tejpal Hospital near CSMT. The state government-run hospital built in 1874, was designed by Colonel Fuller in early English Gothic style. Its colonial architecture, with high ceilings and large windows designed for better ventilation, speak of the healthcare design principles of the era.

1874

The year the hospital was built

Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College, Tardeo

Another famous institution named after Tejpal is the Sanskrit College. Established in 1866, it was one of the first institutions dedicated to the study of Sanskrit and classical Indian literature. This institution is also located near CSMT. The college has significantly contributed to the preservation and promotion of Sanskrit, nurturing generations of scholars and educators. On December 28, 1885, the Indian National Congress was founded on its premises. In 1985, the centenary of the Indian National Congress, a plaque was put up at the college’s Mathuradas Vissanji Memorial Hall, where the delegates gathered for the meeting to form the party a century ago. The plaque reads: “On the 28th December 1885, a band of gallant patriots laid the foundation of the Indian National Congress, which has built up, stone by stone as the pledge and symbol of the invincible purpose to secure to India their motherland their legitimate birth-right of Swaraj.”

1885

The year the Congress was founded on the premises of Sanskrit College

Mota Mandir, Bhuleshwar

When mid-day got in touch with veteran writer Saurabh Shah, whose book, Maharaj Libel Case, inspired Maharaj, he clarified that his docu novel traces a legal case between Karsandas Mulji and Jadunath Maharaj, the religious head of the Vallabhacharya-established Pustimarga Vaishnav sect headquartered in a “haveli” or temple in Surat. While the film’s narrator locates the haveli in the neighbourhood of Kalbadevi in pre-independent India, and it looks like it cannot be anywhere else but on a set at Film City, we think that’s creative liberty a screenwriter can be allowed. For you, the heritage enthusiast itching to walk the trail that traces landmark moments and personalities from the film, there is Mota Mandir Haveli in Bhuleshwar. Dedicated to Lord Balkrishnalalji and Lord Shree Daujidayalji among other deities, Mota or Vada Mandir (“the big temple”) had a wooden structure that dated back more than 200 years. It is now spiffy and Makarana marble-forward. It continues to be an important site for the Vaishnav sect of Hinduism associated with the trading communities in Mumbai.

200

No of years since original wooden structure was built in Mumbai

Great Western Building, Shahid Bhagat Singh Road

The case Mulji fought against the spiritual leader was heard at the court housed in the Great Western Building at Lion Gate. Originally known as Admiralty House, it’s a colonial landmark. Built in the early 1764, it was initially the residence of the Admiral and later went on to serve as the seat for various administrative functions. In the 1800s, it served as the High Court of Bombay. Later, it was also home to the Governor of Bombay. Then it served as a hotel, and later, the rooms were split into rental commercial spaces. You’ll spot it from a distance, thanks to Rajesh Pratap Singh designer store at the ground level. Take a closer look at the coat of arms under the arched sign that bears the building’s name.

1764

The year the monument was built as Admiralty House

Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, Byculla

The film identifies Ramchandra Vitthal Lad, fondly called Dr Bhau Daji Lad, as Jadunath Maharaj’s personal physician, and someone who testified against the latter in court alleging that he had contracted syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that’s the result of unsafe sex with multiple partners; in this case, the scores of women that the guru exploited.

Philanthropist, historian and surgeon Dr Lad’s contribution to the city is immense, and one of its most iconic symbols is the city’s oldest public museum located in Victoria Gardens, now Rani Baug. Formerly called Victoria and Albert Museum, it was renamed in Dr Lad’s honour in 1975. Established in 1872, the museum showcases an enviable collection of decorative and industrial arts, photographs, and cultural artefacts.

Unlike the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sanghralaya, which focuses on commercial and modern art, the BDL museum displays antiques and artefacts which highlight Mumbai’s historical and cultural evolution. The museum is unfortunately shut for renovation, and history enthusiasts have long been waiting for its doors to open, so for now, we suggest you walk its gardens and courtyard and take in the majestic façade which is an example of the Renaissance Revival architecture.

1975

The year the museum was renamed after the philanthropist

Dadabhai Naoroji, Hutatma Chowk

Dadabhai Naoroji, or the Grand Old Man of India, watches over the iconic South Mumbai landmark of Flora Fountain from his seat near Oriental Building. The arterial road stretching from CST to Kala Ghoda is named after the leading reformer of the 19th century, scholar and the first Indian-Asian to be a member of the British parliament.

History buffs, and we are sure even the Parsis, are miffed at his portrayal in the film, as the founder of the Anglo-Gujarati newspaper Rast Goftar, hesitant to publish incriminating articles against Jadunath Maharaj because he fears that the publication could lose its Vaishnav readership. Dinyar Patel, the author of Naoroji’s biography, Naoroji: Pioneer of Indian Nationalism, says, “First of all, there’s no surviving evidence for this. Secondly, Naoroji had already attracted controversy and vituperative opposition for his progressive religious views within the Parsi community; it is a complete misreading of history to cast him as a cautious figure when dealing with a fellow reformer’s views. Thirdly, by 1861, Naoroji was settled in London and his association with Rast Goftar was, obviously, quite limited.

Also, I don’t think Rast Goftar would’ve had particularly wide circulation amongst Vaishnavites—its target audience would have remained Parsis—and it had already established a reputation for attacking religious dogma and orthodoxy, whether Zoroastrian, Hindu, or Muslim. A devout Vaishnavite would be reading something else, and the Rast Goftar wouldn’t have compromised its reputation for social and religious reformist views.” A selfie with one of the foundational figures of India’s modern political history at this iconic location will be worth your while, we think.

With inputs from Nimesh Dave

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!