An urbanist and environmental engineer pair curious about the potential of taming Mumbai’s most capricious river fashion five opportunities that can alter the course of its future

Urbanist Sahil Kanekar and environmental engineer Kartiki Naik of World Resources Institute (WRI) India stand on a bridge on the Mithi river. The river has been channelised using retaining walls (behind), as a flood-protection measure. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

The Mithi river has a most curious relationship with the city. It’s the silent mover, still and languid on most days, forgotten almost, hidden between retaining walls, mixing daily with grime and filth without complain or too much push back. In the monsoon, it turns into an unrecognisable beast. Torrid, bumbling and rather, perilous. The deluge of 2005 was exacerbated by the raging Mithi river, leading to deaths and forced evacuations. Even today, every monsoon, the desilting of Mithi remains top priority for the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation.

ADVERTISEMENT

Urbanist Sahil Kanekar and environmental engineer Kartiki Naik of World Resources Institute (WRI) India chanced upon the capricious Mithi River accidentally. “In 2021, the Marol Cooperative Industrial Estate approached WRI India to be a knowledge partner in the conceptualisation and development of a public space on a land parcel they owned,” says Kanekar, who is senior programme associate for urban planning at WRI India. “In the DP, this particular land parcel, which is along the path of the Mithi river was reserved as an open space—conceptualising it as a public space hence, made complete sense.” There was, however, one tiny issue. During development of the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP), WRI India had created a “heat stress map” or “land surface temperature” that highlighted the urban heat island effects within the city. “This space was among the locations found to be under tremendous heat stress,” says Kanekar. And so, instead of opting for a garden-like space, the team felt what had to be prioritised was increasing the tree cover on this land parcel, while making it accessible to citizens. The proposed urban forest hence, began with the primary objective of mitigating heat risk. A site visit led the team to discover more such land parcels further upstream. “We came up with a larger vision—what if we combined these land parcels together? We would be able to create a linear, kilometre-long park, where citizens could also enjoy a riverfront.”

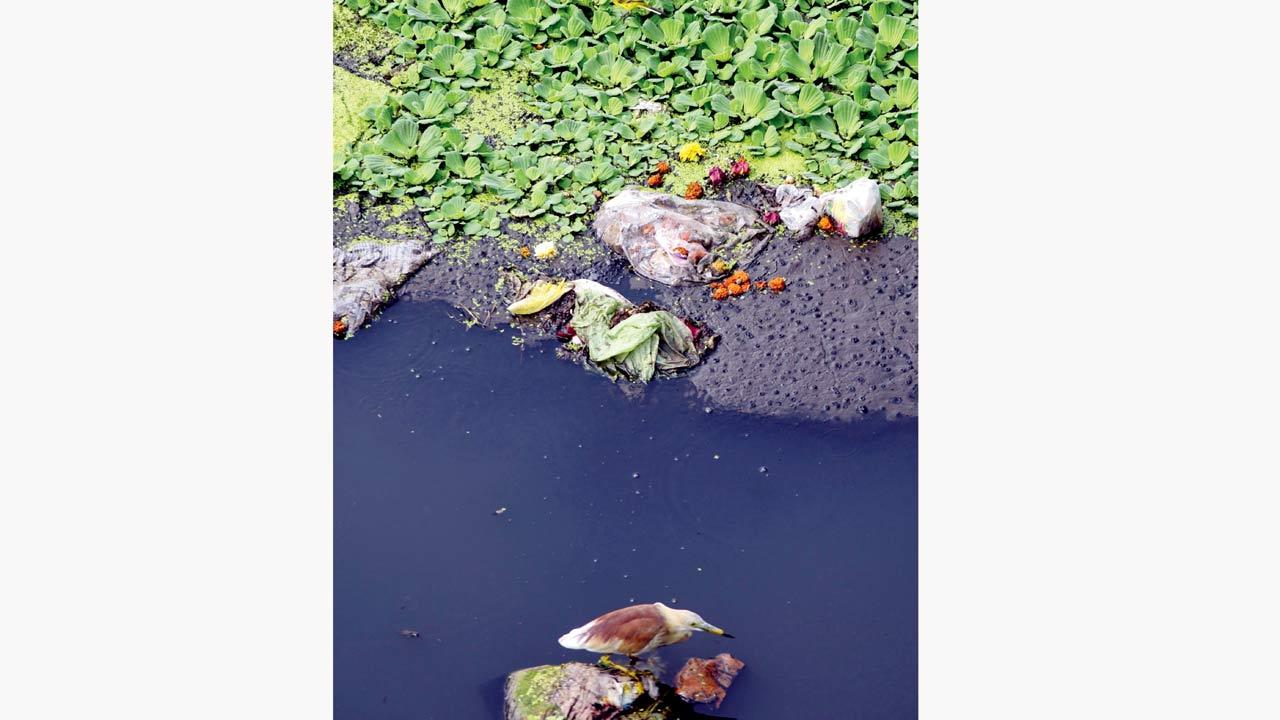

The team at WRI India has proposed a plan to revitalise a land parcel along the Mithi River in Marol as an urban forest. Hyacinth growth has “diminished the river’s conveyance capacity”.

The team at WRI India has proposed a plan to revitalise a land parcel along the Mithi River in Marol as an urban forest. Hyacinth growth has “diminished the river’s conveyance capacity”.

The potential they saw in the one-km-long stretch near Mithi, made them also wonder about the scope of creating buffer zones along the entire 17 km-long stretch of the river. Kartiki Naik, who is Programme Manager, Urban Development, WRI India, adds, “We wanted to explore our curiosity about river-side buffers, seeing if there was room for the river [to expand], and room to setup storm water management, and natural treatment systems, while providing citizens access to the river.”

This curiosity led them to pore over a Google Earth map, where they identified open and vacant spaces, or those untouched by urbanisation near Mithi. Abhijit Waghre, a former intern at WRI India, was given the task of walking along the river in May 2022, in the peak of Mumbai’s summer, and taking photos as part of the documentation initiative. “We asked him to observe the condition of the retaining walls, identify the settlements along the river, the infrastructure in and around, and locate the outfalls [the place where a river, drain, or sewer empties into the sea, a river, or a lake] and if these outfalls were coming from the settlements,” says Kanekar. “As far as the open spaces went, we told him to see if these spaces [as seen on the map] were even visible on ground,” adds Naik. It took him around six days to complete the walk, says Naik.

Once the documentation was complete, Naik and Kanekar went back to the drawing board, exploring opportunities available to improve the health and flood-resilience of Mithi. Their observations have been published as a three-part photo essay that’s now available on WRI India’s website. Their final piece, a result of a near year-long exercise of revisiting the photos from the walk, was published on February 27.

Mithi river, the authors share in their essay, originates from the Vihar Lake outfall and has an inlet from Powai Lake further downstream. “The region, just after the Vihar outfall, is dry during the summer months, consistent with the natural state of the river. Barring this short upstream stretch between Vihar Lake and Filterpada, a notified slum, that still seems to preserve the riverine ecology of the Mithi, the river bears no resemblance to its natural form further downstream. This is the only place where the Mithi is accessible to the public when it still bears some semblance to a river,” they write in the essay.

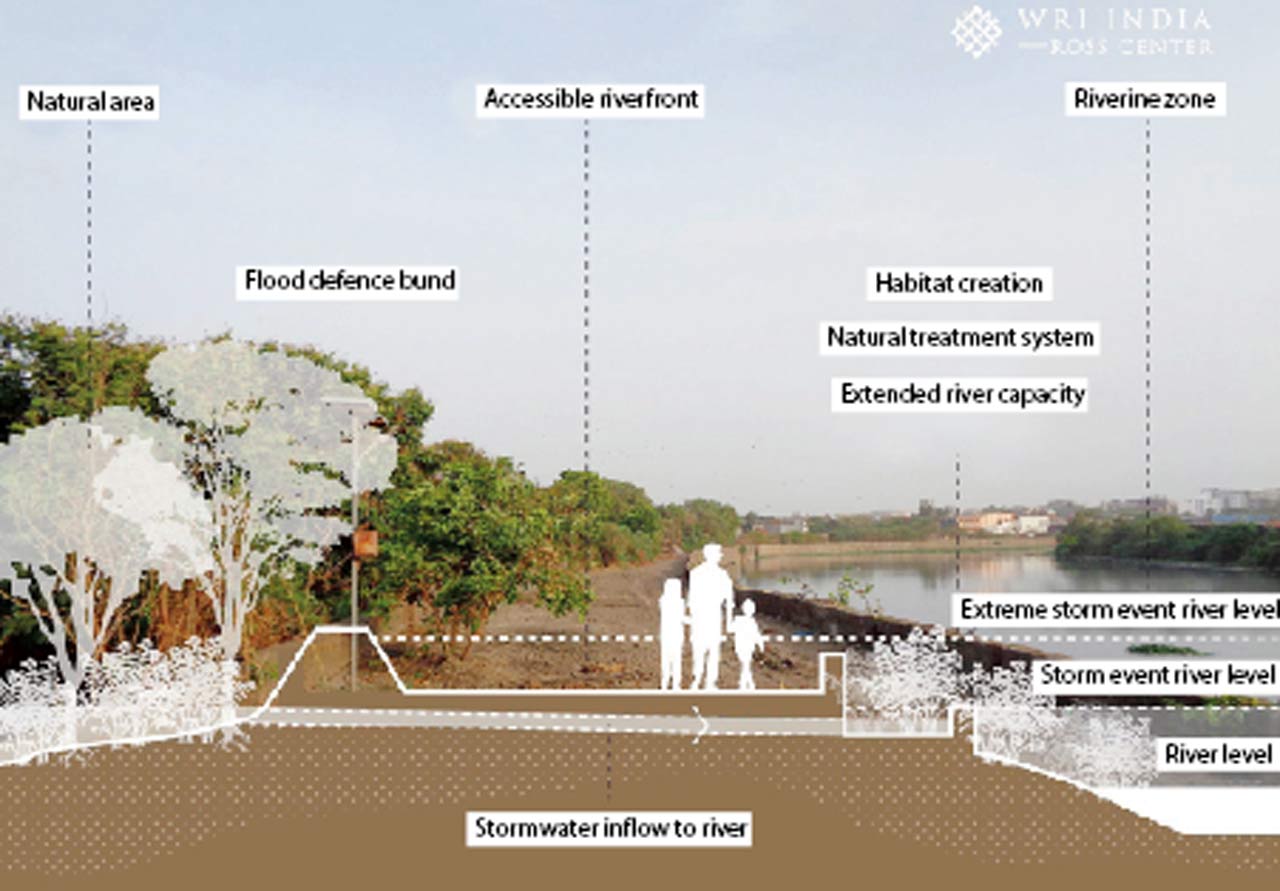

Conceptualised accessible multifunctional water-sensitive riverbank with expanded stormwater capacity and riverine biodiversity. PIC/Abhijit Waghre, WRI India. graphics/Sahil Kanekar, WRI India

Conceptualised accessible multifunctional water-sensitive riverbank with expanded stormwater capacity and riverine biodiversity. PIC/Abhijit Waghre, WRI India. graphics/Sahil Kanekar, WRI India

The first part of the essay explored the entire riverine ecosystem and the many gaps. “Mithi is an urban river, but it comes with its own complexities,” says Naik, who has a background in urban water management. She describes it as a “long-trained river” that has been channelised using retaining walls, as a flood-protection measure. “But at some points we also observed that there were challenges to train it, because there were utility lines or roadways built across the riverbed resulting in increased vulnerability to flood,” she adds. “Then, sometimes, it’s difficult to desilt the river, only because there’s a [retaining] wall there.”

Even building a retaining wall brings its own set of problems. For starters, they write that the equipment required to build the retaining wall can be used only from the riverbed. This means that temporary ramps are built along the riverbed using soil to enable construction vehicles to access the floor. The soil gets deposited in the river, creating bottlenecks in the river natural’s course and also affecting its flood resilience.

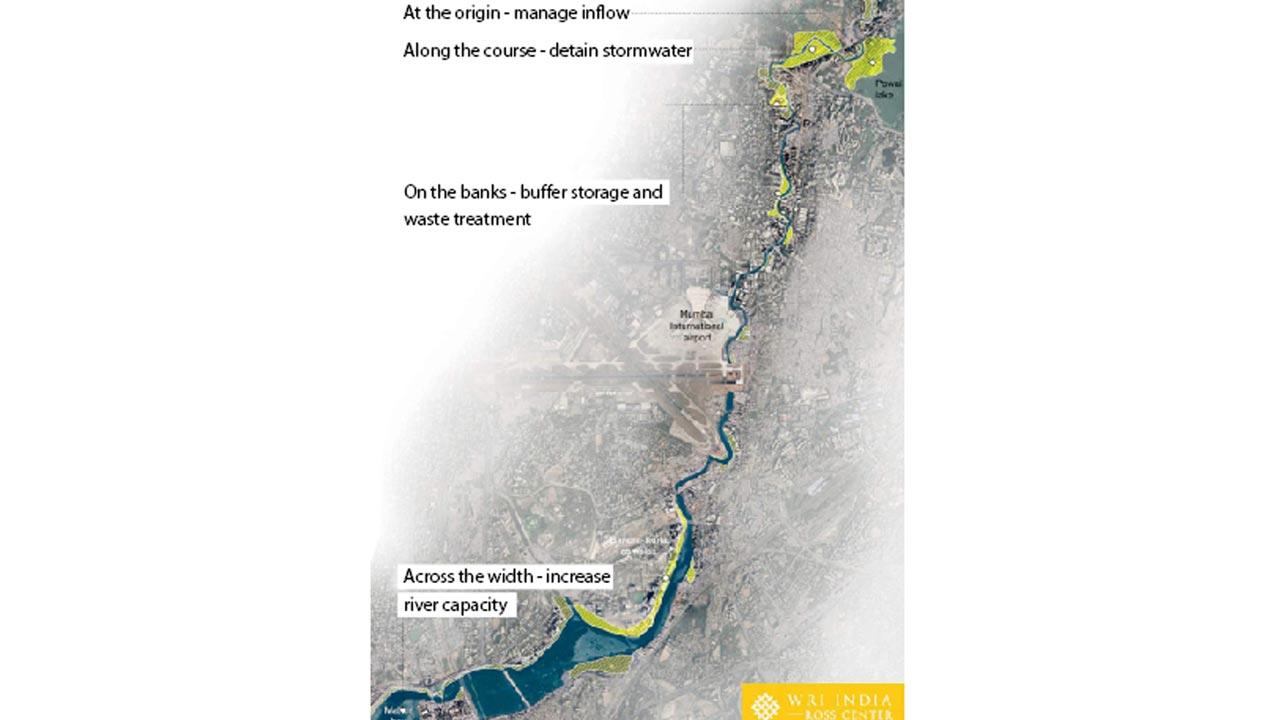

Integrated river management to prioritise stormwater and waste management, accessible green spaces, and biodiversity. Visualisation/Sahil Kanekar, WRI India; image by Google Earth

Integrated river management to prioritise stormwater and waste management, accessible green spaces, and biodiversity. Visualisation/Sahil Kanekar, WRI India; image by Google Earth

Earlier this month, mid-day had reported that the BMC had allocated R46 crore—of the total R226 crore set aside for nullah-cleaning—for cleaning the Mithi this year. While its desilting is an essential annual pre-monsoon exercise, the authors observe that moving beyond such maintenance measures could improve the river’s flood-resilience.

Another essential part of the essay was mapping settlements, industries and establishments along the Mithi and reading into the vulnerabilities these create along its course. “The hyper urbanisation along Mithi is a problem... it is dense and constantly evolving,” says Kanekar. The storm water systems rely on Mithi for drainage, but the settlements abutting the river act as a disadvantage. There have been reported cases of household and community toilet wastewater entering storm water drains, eventually polluting the river.

Further, large volumes of waste from industries—according to the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board’s Action Plan for Mithi River there are 947 industries along Mithi’s banks—also find their way in. The authors highlight how solid waste, desilting ramp remnants and hyacinth growth “diminish the river’s conveyance capacity”.

One particular area, along the banks, that the authors came across through Waghre’s documentation, was seemingly natural and uninhabited. “But it still had a retaining wall, separating that area from the river,” recalls Naik, adding, “That really got us thinking if there was a way to protect and enhance the natural flood-resilience capacity of the river.” Many rural rivers, she cites, are allowed to expand along the banks. Can we make a little more room to accommodate this urban river?

The question prompted them to explore opportunities available for such a possibility. “For that, one has to stop seeing the river as a drainage pathway alone,” says Naik. “There are a lot of experts working on Mithi. And the government has also introduced a slew of initiatives. We have the technical know-how, and we have the willingness, so there is definitely scope to do something different,” she thinks.

In the final part of the essay, Naik and Kanekar make five observations to adapt open spaces for absorbing and holding water at strategic locations along the

river’s stretch.

The first is holding excess storm water flowing to the river at the origin. A potential, they share, is to have Powai Garden house an overflow channel to the river. “It could play a larger role as a floodable landscape to store excess storm water. Creating such buffer storage would involve integrating natural ponds and streams into the garden design, to detain excess flow to the river,” they write.

Kanekar explains: “Most of the flooding locations are downstream, but the solutions need not necessarily be downstream... they can be upstream and mid-stream as well.” Naik adds, “If we have a natural riverbank upstream, it can add to the space that the river can occupy. This will help reduce the flow downstream to the more urbanised areas during extreme rainfall.” It also helps buy time, especially when heavy rainfall is accompanied with high tide, which could lead to a flood-like situation in vulnerable spots.

Kanekar says that the second opportunity is further downstream, when the river is flowing through a relatively natural area that is uninhabited—“opening this natural space could allow the river to swell during periods of heavy rainfall”. This, he says, would be along the lines of what was done as part of the Room for the River project in the Netherlands—designing the area as a floodable space to protect downstream urban areas.

The next potential, they say, is multi-functional land use. “Recreational places like gardens and maidans can also be used to hold excess storm water for that one day of the year [when river water surge submerges storm water drain outlets to the river],” says Kanekar. Naik says such typically permeable grounds can be designed in a way that they can retain more water on the surface. The opportunities, they say, would require cross-departmental efforts involving the BMC’s storm water drainage and garden departments, as well as experts on storm water management, greening, biodiversity and urban design.

Naik clarifies that this project has stemmed purely out of curiosity, and is not a survey for a local body. “But it has made us think about urban rivers, and how we need to re-look at them.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!