A pre-primary school teacher who turned revolutionary, and a 10-year-old who terrorized the colonisers. Abhijeet Bhalerao, an Income Tax officer from Mumbai, is on a mission to shine a spotlight on India’s un-celebrated revolutionaries; and their fellow freedom fighters who betrayed them

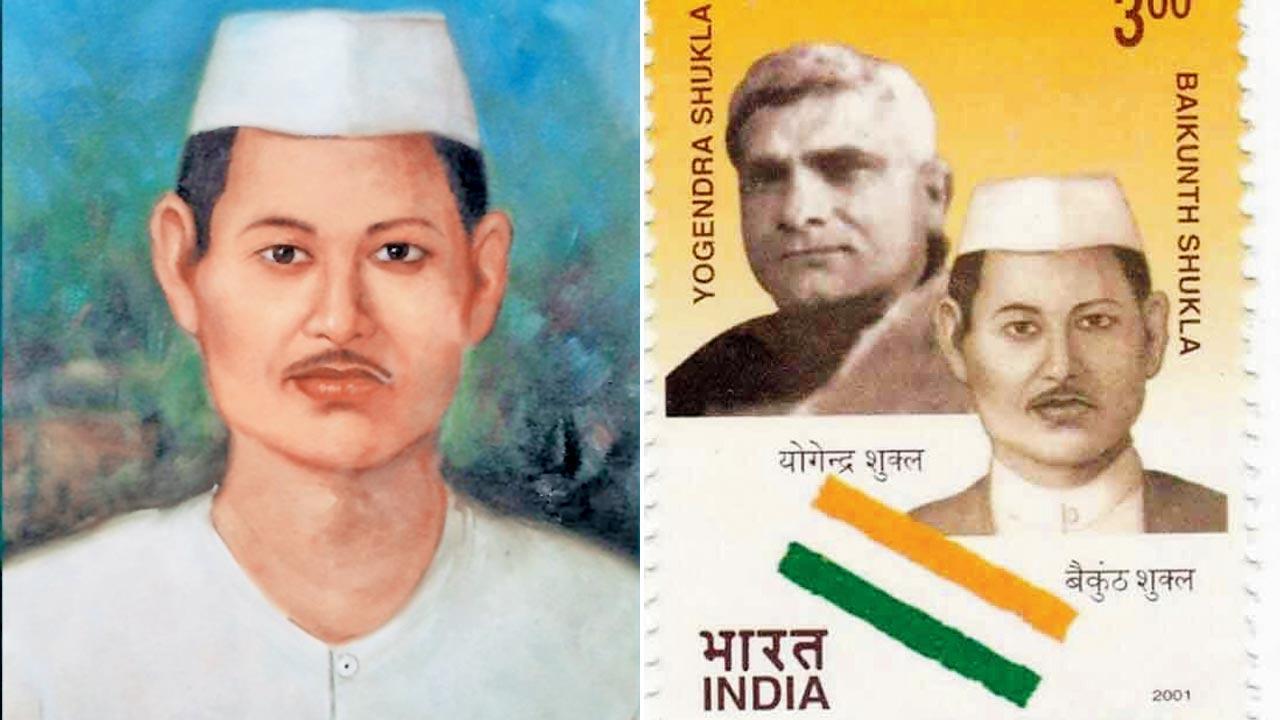

An oil painting of Baikunth Sukul, and the postage stamp featuring him and Yogendra Shukla, a freedom fighter who was his relative and who groomed him to avenge Bhagat Singh’s death

Abhijeet Bhalerao is a working-class hero—researching his obsession-of-the-moment after midnight, and writing about it on the commute. What his fellow commuters on the Goregaon-to-CST local could not have guessed is that the Income Tax inspector was on a trail dampened and dissolved by nearly a hundred years to give several little-known freedom fighters their due.

ADVERTISEMENT

“I consider my book to be part of the subaltern history,” the unassuming Bhalerao tells us over a video-call from his native place, Hingoli, “and I am interested in revolutionaries who were stabbed in the back by peers. We think of the freedom struggle only in terms of us against the British.”

Abhijeet Bhalerao is an Income Tax inspector, and took three years to research and write his latest book that centres around the assassination of Phanindra Nath Ghosh

Abhijeet Bhalerao is an Income Tax inspector, and took three years to research and write his latest book that centres around the assassination of Phanindra Nath Ghosh

The Man Who Avenged Bhagat Singh (Penguin Random House) is Bhalerao’s second book and is dedicated to the pre-primary school teacher Baikunth Sukul from a village in Jabalpur village, who was the same age as Bhagat Singh, both born in 1907. Bhalerao’s primary passion is Maratha War strategy, so what deviated him from that and steered him towards this revolutionary from the North?

“I fell in love with Bhagat Singh when I translated, and brought to context, the diary he kept while on death row in 2015,” says the Goregaon resident. “Singh wrote a total of four books while imprisoned, but most of them were destroyed by the British. This one [that survived] contained quotes from celebrated Western authors and thinkers, and I guess they didn’t subdue it thinking he was praising their culture. But why would a man awaiting death collect quotes from famous people? I realised that these were code for his dream about an independent India. He covered every aspect—women’s liberation, child labour, the role of farmers, the economy…”

Bhalerao has written the book as fiction to entice young readers, but the incidents and characters are rooted in reality and only thinly veiled. It covers the small incidents around this crucial hanging of the only 23-year-old freedom fighter. “Bhagat Singh surrendered after the bombing of the Assembly—that was the HSRA’s [Hindustan Socialist Republican Association] plan,” says Bhalerao. “The bomb was built only to cause commotion and not casualties, so that he would be arrested and bring attention to the cause. He also knew that the British would link him to the Saunders case (the killing of assistant superintendent of police John P Saunders in 1928), but was confident they didn’t have any proof. But his comrade, Phanindra Nath Ghosh, betrayed Singh.”

Ghosh was the Bihar state head of the HSRA, and turned the King’s Witness in the King Emperor Vs Sukhdev, Bhagat Singh and others Case. “It was for money, and of course, personal safety,” says Bhalerao, “but after that, Ghosh turned approver in four more cases, and because of him, six revolutionaries were sentenced to death by hanging, and around 50 more were sent to life imprisonment in the Andamans.” An unsuccessful attempt on Ghosh’s life was also made in Jalgaon Court in Maharashtra.

After Bhagat Singh’s execution, pamphlets from Punjab were circulated in Bihar, sneaked in through newspapers, asking: Daag ko dhoge ya dhovoge? Will you carry this blot or dare to wash it? Sukul took this as a personal insult to the Bihar state, and was groomed by a relative called Yogendra Sukul, who was already a HSRA revolutionary, to avenge both Singh and the state. “My literary agent, Suhail Mathur, believed in this story and helped me in every way to get it published,” says Bhalerao, who took three years to write the book which will be released on December 18.

But how does one find out more about a hero who is not well-known even in his own state? “Sukul was the subject of a book by a former commissioner of I-T, Nand Kishore Shukla, who discovered the trial documents, compiled and published it [The Trial of Baikunth Sukul: A Revolutionary Patriot, Har-Anand, 1999],” Bhalerao says explaining the arduous process, “I scoured the national archives, CID reports, accounts of revolutionaries, and read every available newspaper from that era. I even Googled advertisements for a particular brand of petroleum jelly—Hazeline Snow—popular at that time because I read in one account that Sukul applied it to the wound of a fellow revolutionary, thinking it might lead to some information about him.”

Another hero he found in the process was 10-year-old Yashpal, whose last name is lost in the annals of history. His father was the editor of a newspaper called Milap, and he had an elder brother, Ranveer, who was later hanged by the British for his revolutionary activities. He was secretary of the Bal Bharat Sabha in Lahore, and inspired by Bhagat Singh, would rally children from his gully and attack constables. He was caught in July 1930 and sentenced to one month of imprisonment, but released on a bail of Rs 1,000 paid by his father. “In November, he was caught again for hitting a constable and sentenced to three months of imprisonment, and three years of rehabilitation—such was the fear he sowed in the colonisers that they felt he could grow up to be a big threat. This news reached London, with newspapers talking about how The Raj was not treating juveniles well. A telegram was sent from the Palace ordering a CID report. Meanwhile, the people of Lahore gathered Rs 10,000 for his bail—this was a time when one tola of gold cost only Rs 18, so it was an enormous amount. I want young people to know these heroes.”

Bhalerao is currently researching three other books, one on the conspiracies surrounding the crash of the Kashmir Princess flight in 1955 which was chartered by Jawaharlal Nehru to carry the then premier of China, Zhou Enlai. With experience from his day job in I-T’s Investigation Wing, Bhalerao is sure to find more gripping evidence than what we know now.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!