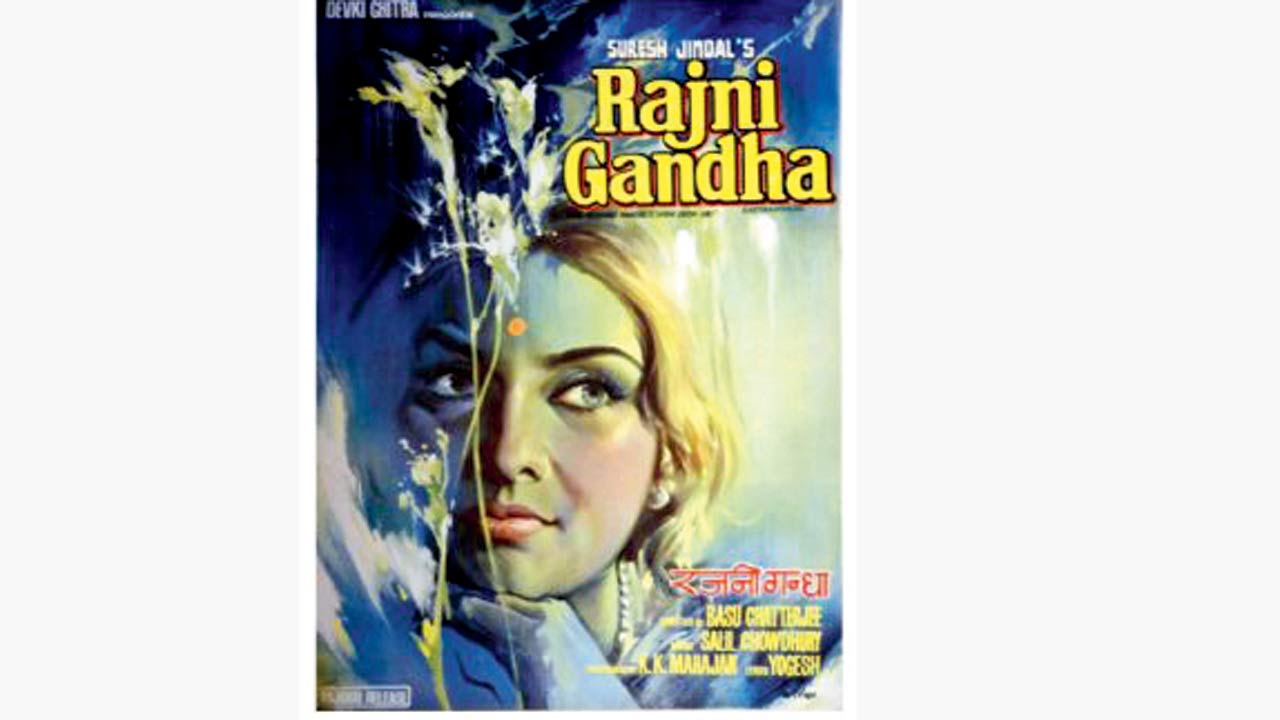

It was Shashi Kapoor and a host of other big stars, who Basu Chatterji first had in mind for the lead pair of his 1974 film Rajnigandha. A new biography of the late filmmaker discusses how the ‘simple-looking’ Amol Palekar made the cut

Rajnigandha’s lead pair Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, who play Sanjay and Deepa, were later seen in Chatterji’s 1976 film

Like most small-towners, Basu was an early riser. Post Piya Ka Ghar, he would be at work by 7 am. By 8.30 am, the ceiling fans would be switched off in the rooms where the others would be sleeping. It was their wake-up call. Those who woke up early would find Basu in his chair, sometimes on the floor, writing his screenplays. Except for the days when he had a morning shoot. This was the time when Basu cut down his professional assignments for Blitz. The script of Rajnigandha happened during the early morning sessions when Piya Ka Ghar was in the making.

ADVERTISEMENT

The first actor Basu had in mind for the role of Sanjay was Amitabh Bachchan. He was yet to become the Alpha Male then. History could have been very different had Basu stuck to his original choice. Shashi Kapoor was offered the role of Naveen. Suave, slick, with leadership qualities that extended beyond the college campus to wield influence in college selection panels, he was, as defined by Sulagna Biswas, the original LinkedIn Man. Sharmila Tagore was Basu’s first choice as Deepa. Independent, but not a renegade. Observant, sentimental, committed, steadfast and yet ambivalent. The plan fell through. Shashi Kapoor was fine with playing Naveen, subject to the condition that the film was sold to distributors at the existing rate for a Shashi Kapoor film, something Basu was not comfortable with. Sharmila was out of the contention too, but the reason is not known. Maybe Basu wanted fresher faces.

Chatterji and Dharmendra at the Cairo Film Festival. Pics courtesy/Rupali Guha

Chatterji and Dharmendra at the Cairo Film Festival. Pics courtesy/Rupali Guha

Meanwhile, Basu flew to Calcutta and offered Aparna Sen the role of Deepa. Aparna, who probably had not seen Sara Aakash, felt that the story of Deepa was ordinary. Her refusal prompted Basu to pitch it to Mallika Sarabhai. She was referred by Yogesh. Both Yogesh and Mallika were working in Sonal (1973) then. Basu met Mallika in Ahmedabad and the dates for a few shoots were fixed. However, Mallika was planning to do her MBA and later walked out of the film. In the meantime, Piya Ka Ghar was released in Calcutta. News of its critical acclaim reached the cognoscenti. Aparna Sen, being one of them, had a change of mind and wrote to Basu expressing a desire to play Deepa.

A few days after Basu acknowledged the mail, Aparna came down to Bombay to complete her part of the shoot of Tapan Sinha’s Sagina (1974). Basu met her, and when the discussion boiled down to money, Sen said she was fine receiving in kind as a small film-maker like Basu would find it difficult to compensate her at the market rate. The contract with Suresh Jindal had been finalised by then.

Chhoti Si Baat

Chhoti Si Baat

Said Basu: “I discussed the possibility of giving Aparna Sen a Fiat car. It would have cost us around R32,000. But things began to get topsy-turvy when she refused to work with the Naveen I had in mind—Samit Bhanja, who I had seen in Guddi (1971) and liked. While the producer and I were fine with the monetary arrangements, we started to become sceptical of starry tantrums. This is when we consciously took the decision of taking all new faces.”

The search for rookies thus commenced. Basu, for a short time, had also mulled trying out Rakesh Pandey, but he was preoccupied, as told to the author. “Basu-da wanted me to do Rajnigandha. At the time, I was doing a film with Mohan Segal called Intezar (1973). The set was at Rooptara Studios. Basu-da came down to the set, and said, ‘I am doing a film called Rajnigandha. It is about a girl and two boys. It will take 20 days to shoot.’ I said, okay, when do you want to start? He said next week. I said, ‘Basu-da, I am doing this film, and it will take at least 15–20 days here on this set. I can manage three to four days at the most if you shoot in Bombay.’ He said, ‘No no, the producer might run away.’”

• • •

In addition to his National Award-winning screenplay for Shyam Benegal’s Bhumika (1977), theatre veteran Satyadev Dubey—who people would recall as the weekly waged stevedore who confronts the goons only to be run over by a truck in Deewar (1975)—made one extremely significant contribution to Hindi cinema: Amol Palekar.

Dubey had directed the Hindi play Aadhe Adhure, starring Amol, who was acting in Marathi plays at the time. Basu loved his acting, and Amol was Basu’s original choice for Piya Ka Ghar (1972), but producer Tarachand Barjatya’s son Raj Kumar Barjatya, who was there at the theatre with Basu, opined that Amol was too simple-looking for a hero. Suresh Jindal, however, had no issues in accepting Amol, a postgraduate of JJ School of Arts, Bombay, as the Sanjay of his film. Basu was happy with the onboarding, about which he told the author: “Amol was then working with Bank of India. He was a part-time actor. I was fond of Marathi theatre and had seen Amol in a few plays. He used to come to film shows arranged by Film Forum as well. Raja Thakur, the maker of Mumbai Cha Jawai (1970) had also put in a word. Amol had played a small role in his film Bajiravacha Beta (1971). After he was rejected by Raj, I proposed his name to Suresh Jindal.”

Amol had talked about his first business meeting with Basu with author Balaji Vittal: “There used to be a café named Samovar inside the Jahangir Art Gallery. I met Basu-da and producer Suresh Jindal there. Mr Jindal did not talk during this meeting. But the interesting part was that Basu-da did not talk much either. He narrated the story of the film like this. ‘Amol, kya hai, ek ladka hai, mano tum. Aur ek ladki hai. Nayi ladki hai, Vidya Sinha hai uska naam. Usse miloge tum. Toh, ye dono hai . . . aur . . . yaar ye tum padh lo na [Amol, there’s a boy. You. And a girl, a new actress called Vidya Sinha. You will meet her . . . you two . . . oh, why don’t you read it for yourself].’ Basu-da handed me Mannu Bhandari’s story. Following my acceptance to do his film, he gave me the script as well. After reading that, I kept wondering how someone who was so ill at ease narrating a story could write a screenplay in so much detail. Even the dialogues were there. He was extremely eloquent in the cinematic language. Once you understood that, communication becomes easy.”

Excerpted with permission from Basu Chatterji And Middle-of-the-Road Cinema by Anirudha Bhattacharjee; Vintage, Penguin Random House

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!