With their commercial work being heavily censored, young Dalit artistes are finding a new voice, and employment, on social media

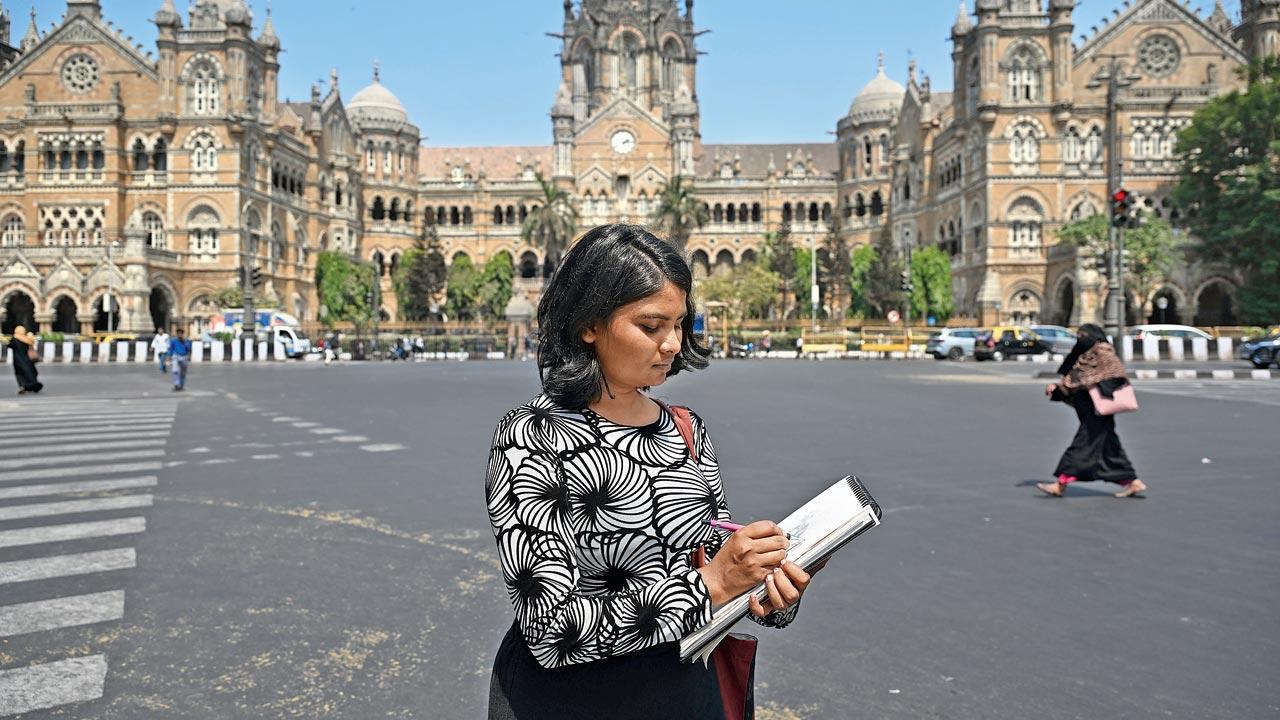

Artist Rohini Bhadarge, Student of JJ School of Arts is seen making a sketch at Fort area, Mumbai. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Since April 1, Instagram almost feels like a research journal of Dalit history. Dalit/Ambedkarite and Bahujan artists have been posting their own anti-caste work, as well as that of their peers. All in a bid to document what today’s youth from the community have to say about what’s going on in the city, state and country.

A significant chunk of contributions have come from artists based abroad, who have posted art to honour their people in the homeland, urging them to keep fighting the good fight. Interestingly, April has always been a significant month for the community; anti-caste icons and social reformers Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar (April 14, 1891) and Jyotirao Phule (April 11, 1827) were both born this month. However, the call to action in 2015 was born out of the heartache experienced by Dalit women activists living in the US, where they were inspired by the Black History Month observed in February.

Artists like Rohini Bhadarge have been putting out their art on social media and want to contribute to the Dalit/Ambedkarite movement by documentating their own struggle. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Artists like Rohini Bhadarge have been putting out their art on social media and want to contribute to the Dalit/Ambedkarite movement by documentating their own struggle. Pic/Anurag Ahire

We ask Shrujana Niranjani Shridhar, an artist and illustrator who goes by the handle @srujangatha on Instagram, why she thinks it originated outside the country. “The women probably felt that they needed to stay connected to their roots and go beyond just that. They recognised the need to document and build an archive of our lived experiences,” she says.

Shrujana, who is now pursuing a Masters degree in New York, was one of the first to interview the collective of women (Christina Dhanuja, Thenmozhi Soundararajan and Maari Zwick-Maitreyi) who started the hashtag #DalitHistoryMonth on social media. “It is amazing how the movement has gone beyond the superficial; it has become a living, breathing thing now. It’s something else to see how we are talking about our history through multidisciplinary art across the world and, of course, our homeland,” she adds.

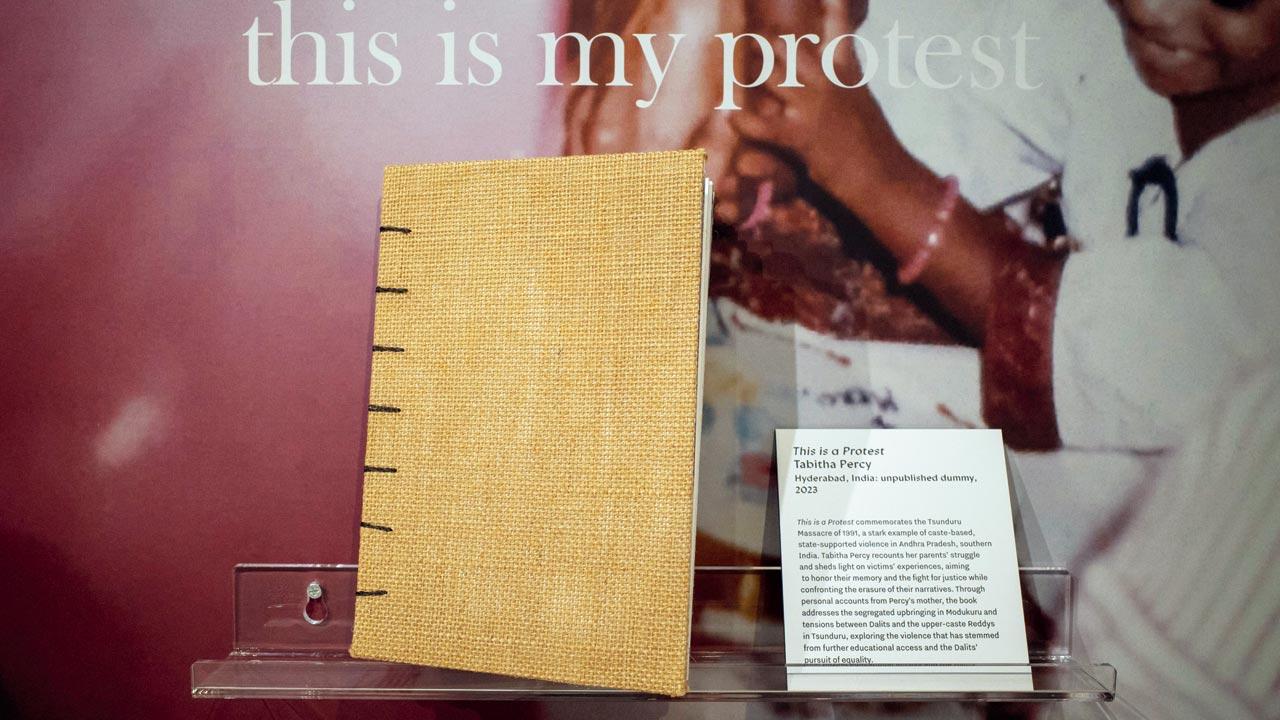

Percy Kaki’s book

Percy Kaki’s book

So why is documentation via art—be it a painting, play or an illustration—so important for the community? “Because our art has been hijacked for far too long, plays are written and performed about our story, paintings are made, awards are won for telling our stories. But now, we are finally telling the stories,” says Rohini Bhadarge, who is pursuing her Masters in Fine Arts at the JJ School of Arts. The 25-year-old multidisciplinary artist (@nili_chimani) pulls no punches and her unapologetic rage seeps through the phone call with us. “We do not have a problem collaborating with Savarnas, but what today’s Ambedkarites and s are crystal clear about is that you [Savarnas] will not be our leader. Unfortunately, this does happen, which is why you see our stories are being told by people looking at our experience from the lens of an observer, using our tools and our art,” she explains, “Which is why I put my work out on social media. Here too, of course, we have to make sure that our rage is not in your face. But at least it’s been a channel for us to tell our story, rather than someone else,” she adds.

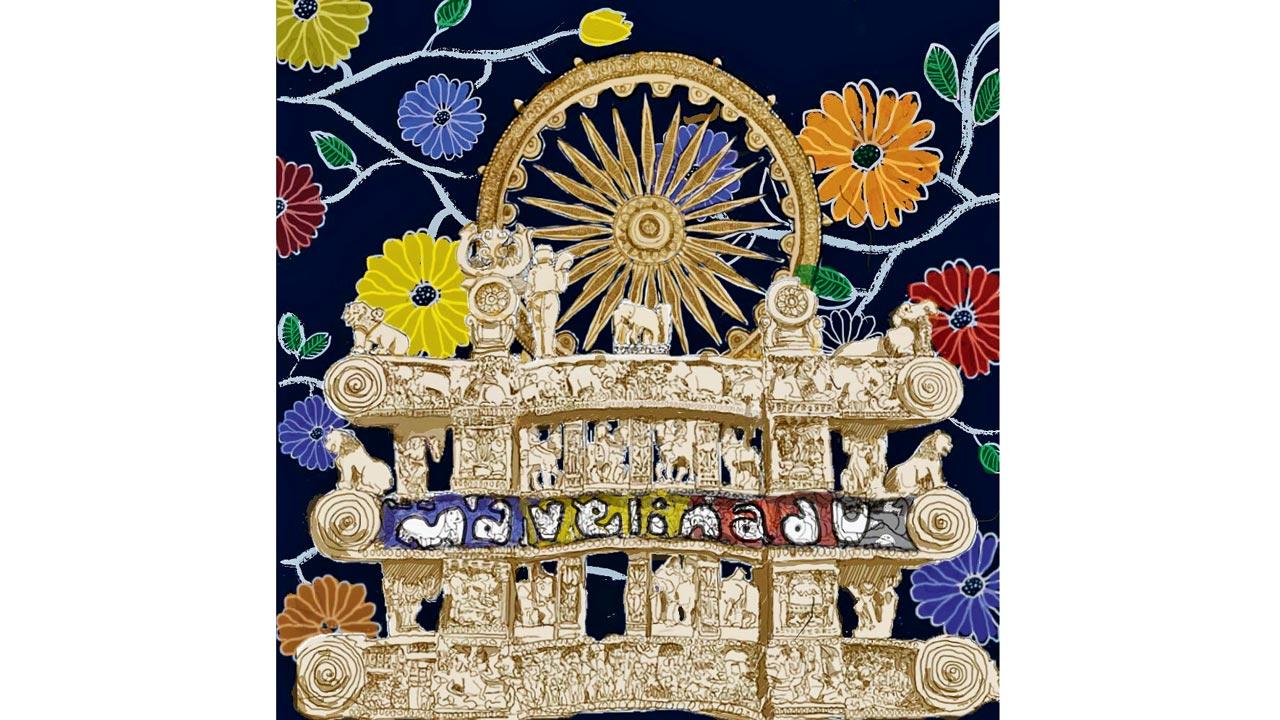

One of the most fearless artists on Instagram is probably @thebigfatbao, her legal name—Bao, a decision that many from the community take to assert themselves. She tells us that trolls have christened her as an “angry person”. Bao has been one of the most consistent participants in the movement, posting an illustration every day in April for the last five years. This year, she embraced her anger through a series that documents the rage of Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi and Vimukta (denotified and nomadic tribes) women. She kicked off the series on the first day with an illustration of Nangeli, a woman who cut off her breasts to oppose the breast tax imposed on Adivasi women in what is now Travancore. “I try to talk about and illustrate all the women whom I have learned a lot from, whom I have taken inspiration from,” she says.

Illustrations of DBAV women by the artist Bao

Illustrations of DBAV women by the artist Bao

“Nobody likes an artist who expresses rage. The world expects us to be extremely sanitised in our approach and output. I didn’t know what to do with all of this anger I have. So I chose to present these women on matchboxes, which for me symbolises fire,” Bao says.

Activism through art can often result in shadow bans or limited reach for artists on Instagram. “I have never felt that social media is a conducive or democratic platform to begin with. It’s specifically meant for the urban, elite, English-speaking people… In the Indian context, anti-caste work is very dangerous; we have to censor ourselves a thousand times before we even post something. It does bring us visibility, but it’s not a source of income for most of us—commercial work is very difficult to come by when you are a political person,” she adds.

Percy Kaki and Vamsi

Percy Kaki and Vamsi

For the community, it’s more about making the best of social media. Take documentary filmmaker Somnath Waghmare, a mill workers son who has documented stories from the DBAV community, such as witch-hunting in the Adivasi community, or the the annual gathering at Bhima-Koregaon, or his 2023 movie Chaityabhumi, that is being released on the OTT platform, MUBI, on Monday.

Waghmare, while familiar with the pitfalls of social media, chooses to look at the good such platforms can do. “The Internet is democratic and has given voice to the marginal media. The mainstream has had to wake up and listen because of the Internet. They had to write about it because it was being discussed on various platforms. The Guardian [UK news publication], wrote about me and, soon, the Indian mainstream media had to follow,” he says.

This is also one of the reasons why his movie has been picked up by an OTT platform. “It’s one of the first documentaries which is about the Dalit conversation through and through going to release on MUBI. There’s no roundabout approach to caste in it; this is a testament to the fact that we are heading to a time where our stories are going global. The world will come to know that Bollywood has zero diversity and the industry is headed for a reckoning globally, where the lack of representation in our art and movies will no longer go unnoticed,” he adds.

For many like Bengaluru theatre artist Vamsi, visibility is why he posts his work on social media. “I am doing this so that I am heard, I am seen, and people like me are heard and seen,” he tells us, his voice radiating anger, “Art reflects oppressive structures. When people talk about caste, it is always about somebody’s death or some violent brutality. There’s no conversation around emotional violence. I’m much more interested in articulating the fact that we have happiness and joy and celebrate too,” he says.

“Social media,” he says, “allowed us to connect. Someone like Bao sitting in Mumbai is able to not just interact with me, but we can learn, work and build together. Every other institutional space are gate-kept [by savarnas],” he adds.

Vamsi has announced that he will be launching his play, Star in Sky, on Instagram (@srivamsimatta) on April 26. The play is inspired by Aakasam Lo Oka Nakshatram, a Telugu story penned by M Suguna Rao on the life and death of Dalit scholar Rohith Vemula.

Vamsi’s set designer, Percy Kaki (@percykaki), is a trained architect and a multidisciplinary artist who is working on a photobook about the coverage of the DABV community in newspapers. Kaki and Vamsi, too, connected via Instagram. The gateway to forming connections is a boon, but the price these artists pay is high. “I am facing a social media burnout,” says Kaki, “There’s a lot of pressure to keep posting [to ensure visibility and followers]. It feels like we are constantly performing online. You always have to put yourself out there, make yourself marketable but also ensure political correctness.”

The upside? The recognition and work. “Most of my work comes from social media. People call and message, asking me to take up projects,” she adds.

Every DBAV artist believes in the power of social media when it comes to the documentation of their collective lived experience. But Shrujana questions if the reason Dalit History Month predominantly exists online is because most of the youth in the community have no offline organisations left to turn to. “The Dalit Panther movement [1970s-80s] was heavily monitored and its leaders were closely watched; that’s how they [powers that be] were able to slowly eradicate their presence. So the youth from the community used whatever was within their means—the Internet and social media—to organise and connect,” Shrujana explains, “We are seeing events, screenings all through Europe and the US. Back home as well, we are seeing this wonderful documentation online. But for most of us, the question now is how to take this effort offline? How should we make this something tangible and bring in true change?”

These are tough questions for the future of the movement. For now, though, Shrujana recognises the impact it has on young community members who may feel alone or vulnerable: “When I see young Ambekarites/Dalits assert their identity through art, it feels like a warm hug from the community.”

2015

The year in which Dalit History Month was founded

This Dalit History Month

What's happening in the online world?

1 Stream the documentary Chaityabhoomi, that talks about reclaiming public spaces

mubi.com/en/in/films/chaityabhumi

2 To watch for free, log on to YouTube: Dr Ambedkar Thoughts Movement (ATM Network)

@DrAmbedkarThoughtsMovement

3 Delve through multiple resource materials, from articles to podcasts

Log on to velivada.com

4 This one is for the readers. Mavelinadu is a publication house and cultural platform, with its pilot project being a magazine that will publish the work of marginalised caste creators both digitally and in print

mavelinaducollective.com

Offline

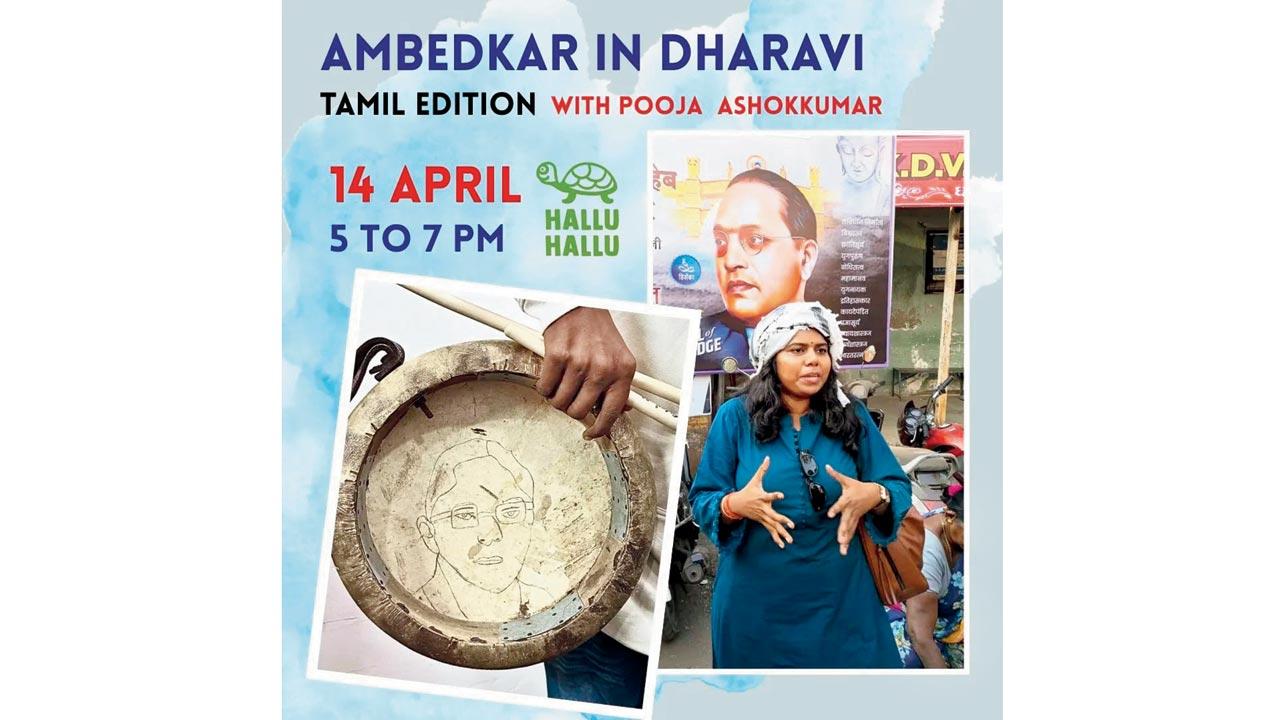

Find Ambedkar in Dharavi

@gohalluhallu

April 14 marks a convergence of Ambedkar Jayanti and Tamil Puthandu, the Tamil New Year.

On this powerful overlap, come to witness the cultural-political unity

Register at https://forms.gle/d8rHAyZGs1hxQXhE9

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!