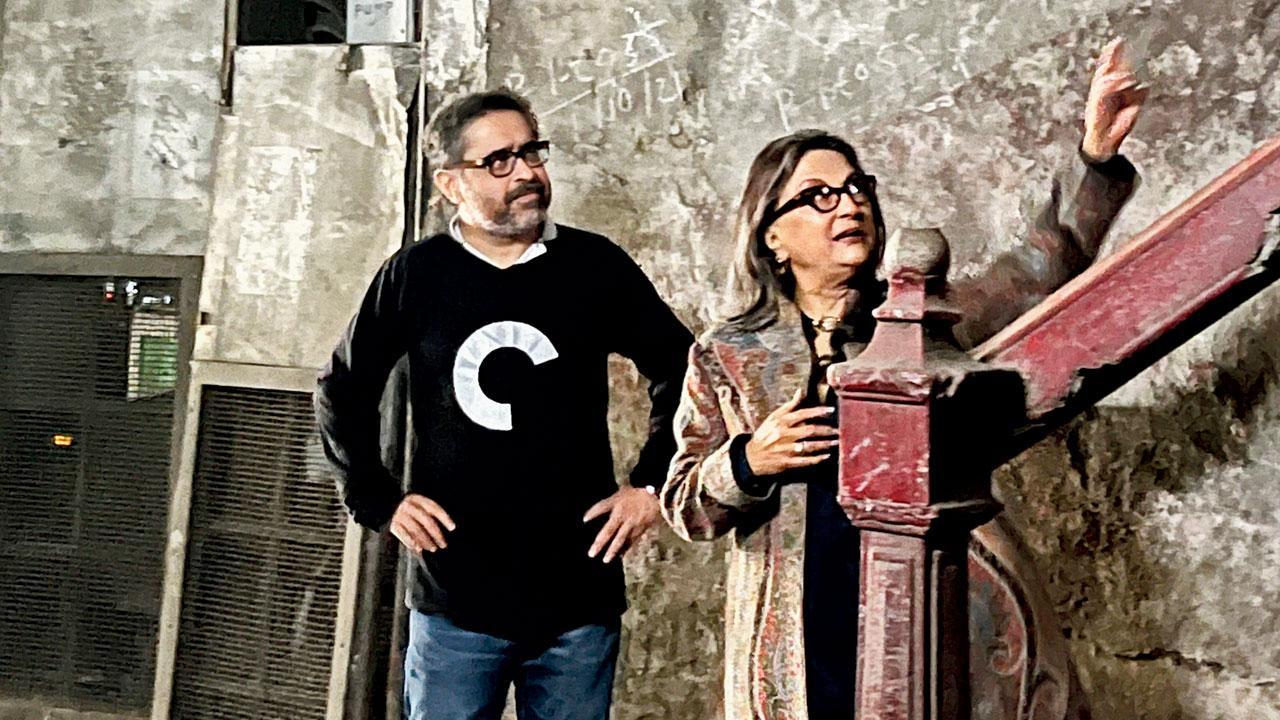

Suman Ghosh takes Aparna Sen back to the locations of some of her early films in a new documentary on her life and work. mid-day gets together with the two filmmakers to discuss cherished characters, influences and changes in Bengali film viewership

Director Suman Ghosh accompanies Sen to the locations where she shot films like 36 Chowringhee Lane, Paroma and Paromitar Ek Din to jog Sen’s memories of working on these projects

I still think that 36 Chowringhee Lane was like a love affair. It’s my first film. I lived and breathed [that film]. As my daughter said, I was consumed by it. But you go past that, you move on. You don’t remain in 36 Chowringhee Lane forever,” filmmaker, screenwriter and actress Aparna Sen tells us on a video call from her home in Shantiniketan. Espousing the lessons learnt from a book like Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, she speaks of how she finds little value in dwelling on past achievements. “It’s more like every time I see one of my older films, all that jumps out at me are the flaws.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Sen’s past accomplishments are however, the focus of Parama: A Journey With Aparna Sen, a documentary by director Suman Ghosh which saw its world premiere at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. It was screened alongside Sen’s own film Paroma, a radical portrait of female self-discovery, which ironically, as Sen tells us, was not invited to any international fest at the time of its release. “It was perceived that the issue it discussed was kind of passé as far as the international audience was concerned. Today, it’s come back [because] they think it’s relevant, but at that time they didn’t.”

“That film still affects me so much,” Ghosh tells us when we ask him of his decision to name his film after Sen’s 1985 National Award winner for best Bengali feature. “‘Parama’ also refers to the female version of the ultimate,” he points out. “In the film I capture different aspects of Rinadi [Sen] and how she has, to my understanding, excelled in each of those faculties.”

Ghosh calls Sen a Renaissance woman, someone who belongs with figures like Amartya Sen and Soumitra Chatterjee, both of whom he has been creatively involved with. “All three individuals have been deeply influenced by Tagore’s philosophy which encapsulates a liberal tradition and a modernist view of life which I think is sadly fading away,” he says. “[Moreover], if you look at history, there are so many women who have contributed in this way, but I haven’t heard the terminology [Renaissance] used for women. So, I’m insisting on using it [for her]”. As a director, he finds in her the perfect welding of the emotional with the intellectual. “She is a wonderful combination of, what Nietzche called, Apollonian and Dionysian qualities—an amalgam of the head and the heart. That is reflected in her films.”

Sen’s directorial debut looms large in Ghosh’s docu, its scenes framing the conversations and literal and metaphorical journeys. Ghosh accompanies Sen to the locations where she shot films like 36 Chowringhee Lane, Paroma and Paromitar Ek Din to jog Sen’s memories of working on the projects, intercutting between scenes from the films and those of her walking through these spaces in the present day. “It was a mixture of two emotions,” Sen tells us of the feelings the revisiting evoked. “There was this surge of nostalgia. But, on the other hand, I was feeling desolate because that entire location had been stripped of the effects that were there, which had helped create the character and the character’s background. These were just bare rooms [now].”

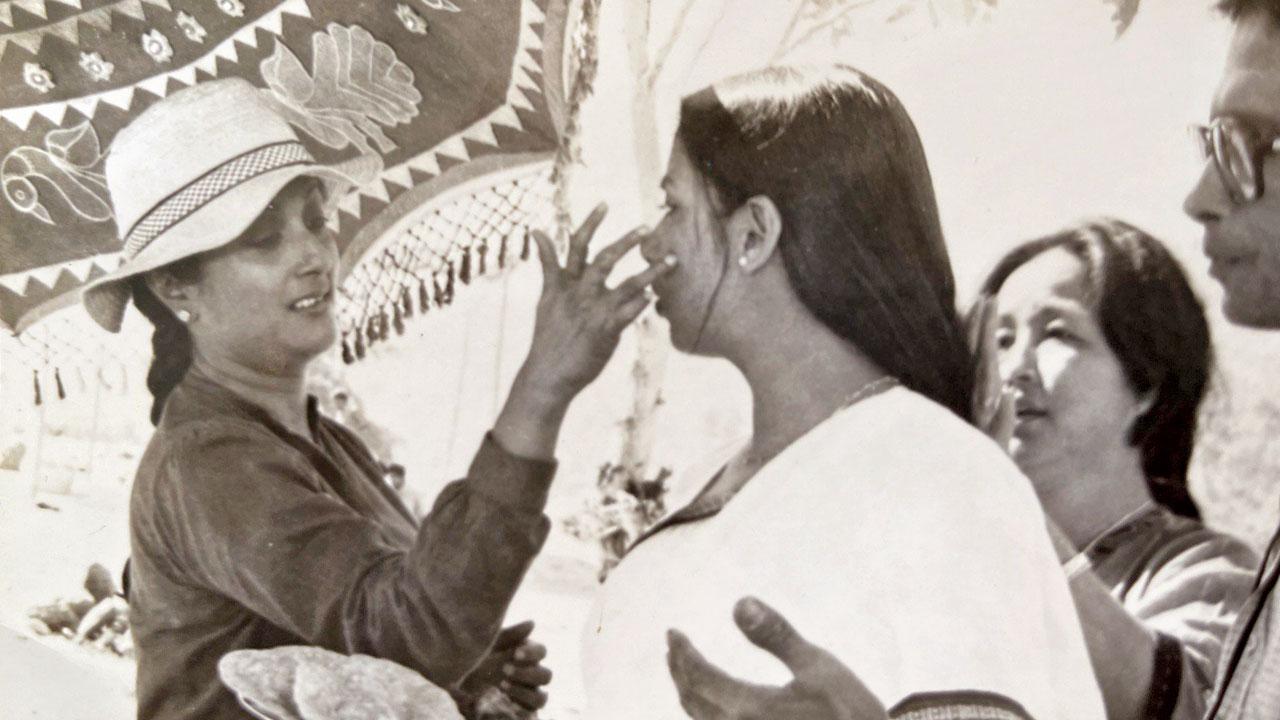

In a moving moment in Ghosh’s film, she speaks of how at the end of the shoot when a film’s sets would be dismantled, she would often be driven to tears at the thought that her characters were dying, that their worlds were disappearing. ‘They are killing Violet!’ she had said of Jennifer Kendal’s Anglo-Indian English teacher in 36 Chowringhee Lane. Always intensely involved with production design, her attention to detail is a trait, she believes, she picked up from Satyajit Ray, a director she worked with early in her career and was deeply influenced by. “I remember that when we were doing the weathering of sets in 36 Chowringhee Lane, I said Violet’s home should be shabby but clean. It’s not full of dust. She would clean the dust; there are little details in there, like pens arranged in a row. She had all the time in the world.”

Like places, characters would produce attachments too. Sen recalls how during the shoot of 1995’s Yugant about an estranged couple, when Roopa Ganguly changed out of her Kanjivaram saree and stripped the bindi off her forehead at the end of the day’s filming, Sen would wonder where her character Anasuya had disappeared. “I wanted to trap them forever in those characters, but I couldn’t. Obviously, you can’t; it’s not fair. They were so badly affected themselves that Anjan Dutt who had a light beard in the film, shaved. He said he had to get out of the role. It had gripped us all. After Violet Stoneham, I felt closest to the characters of Yugant.”

“She was imbibing… at the feet of some of the finest masters,” author, actor and Sen’s husband Kalyan Ray notes at one point in Ghosh’s documentary. Sen began her career as an actress, and Ghosh’s film touches on her work with directors like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Tapan Sinha, in Merchant-Ivory productions like Bombay Talkie as well as in more commercial fare in the ‘70s and ‘80s. As the daughter of critic, filmmaker and translator Chidananda Das Gupta who was one of the founders of the Calcutta Film Society, Sen was “a film society kid” and filmmakers like Kurosawa, Antonioni, Bergman and Truffaut impacted her profoundly. But it was Ray, who was part of her DNA, like Tagore. “I’ve inherited him like you inherit your parents’ or your grandparents’ blood sugar or blood pressure.

Shabana Azmi who has worked with Sen on films like Sati, 15 Park Avenue and Sonata speaks in the documentary of a teasing friendship that they have shared over the years

There’s nothing I can do about it. It’s there in my bloodstream. But I have made a conscious effort to not be imitative or derivative.” Her use of leitmotifs, she says—such as in Paromitar Ek Din with songs coming back, fans whirring, top shots, characters sitting and eating alone—is a product of that unconscious influence, a feature she notices in the work of Rituparno Ghosh too. “Ray often used a particular character, situation or dialogue once and then it comes back in the film later with a different, more layered meaning. But all this happens at a very subterranean level,” she notes. “I think that’s the magic of creativity. You don’t really know [where it emerges from].” From Tapan Sinha she says she learnt of the need for actors to be prepared. “Actors shouldn’t meet each other as characters for the first time on my set. It’s most important to do acting workshops because they have to be used to each other’s bodies..”

Ghosh’s documentary draws attention to other aspects of her life and work such as her editorship of Bengali women’s magazine Sananda which tackled divorce, family planning and abortion, and her activism and outspokenness on issues like the Nandigram movement or poll-related violence in Bengal. For Sen, whose latest film The Rapist released in 2021, what has changed between her generation and Ghosh’s is the nature of subjects. “Because of globalisation, audiences have had access to a lot of world cinema, and that has educated some in the language of film,” she observes. At the same time, the tastes of television audiences have been corrupted with regressive material. “There’s also the urban-rural divide, which was not there so much when Tapan Sinha made a film like Haate Bajare for instance, which was seen both in the rural and urban sectors.”

Bengali audiences have long complained about a creative trough in the industry after its glorious yesteryears. Ghosh cites names like Aditya Vikram Sengupta, Kaushik Ganguly and Atanu Ghosh and commercial directors Srijit Mukherji “who have made a fundamental change to Bengali cinema by bringing audiences back in a big way.” “I am vehemently opposed to the idea that nothing has happened after Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Rituparno Ghosh and Aparna Sen. I’m keeping them at their place. But a lot of interesting work is also being done.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!