Then you are trapped, a digital scream competing to be heard in a hall of mirrors.

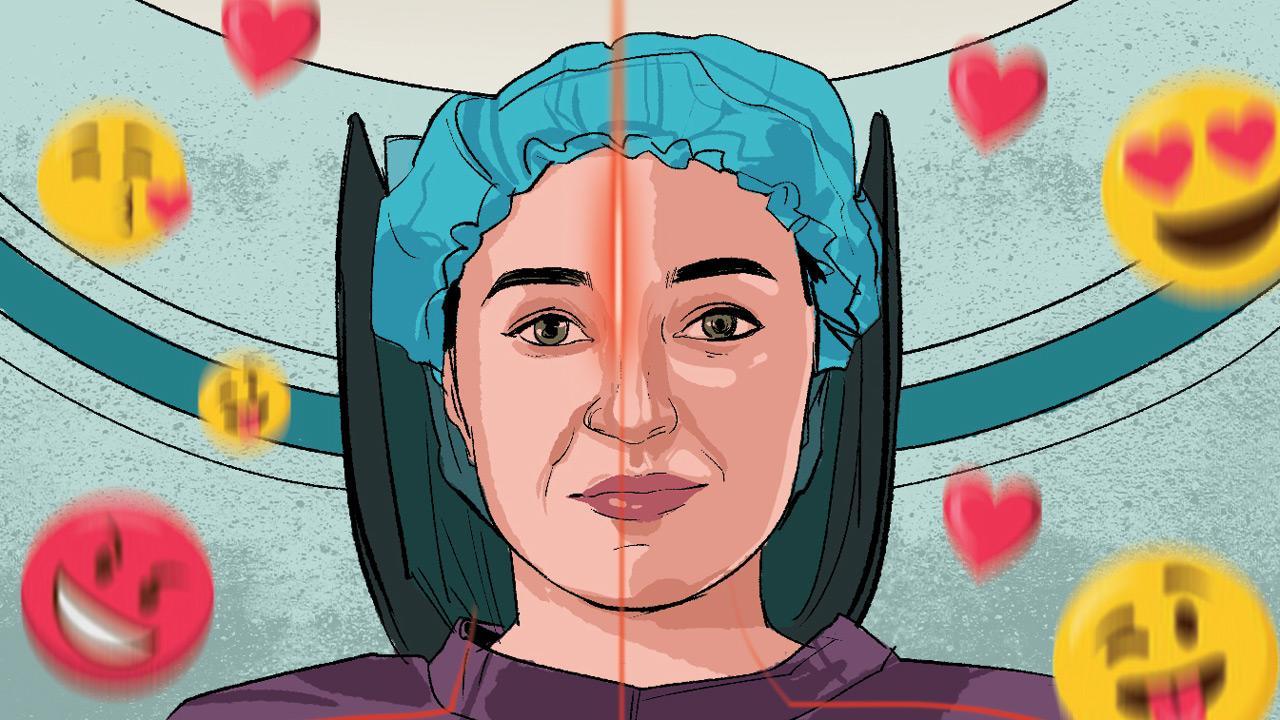

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() The new and highly watchable Netflix series Apple Cider Vinegar joins a growing genre of what I call Scam Girl shows, like Inventing Anna and The Dropout. It is based on the real-life stories of two Australian wellness influencers. Milla, diagnosed with cancer, chooses an alternative healing route, blogs about it like it’s a fairy tale and acquires a large following. Belle, inspired by her, fakes a cancer diagnosis and rides the social media dragon all the way to the top until things go up in flames.

The new and highly watchable Netflix series Apple Cider Vinegar joins a growing genre of what I call Scam Girl shows, like Inventing Anna and The Dropout. It is based on the real-life stories of two Australian wellness influencers. Milla, diagnosed with cancer, chooses an alternative healing route, blogs about it like it’s a fairy tale and acquires a large following. Belle, inspired by her, fakes a cancer diagnosis and rides the social media dragon all the way to the top until things go up in flames.

ADVERTISEMENT

The show plays with several themes with varying success. Chief among them is the idea of the influencer as a remix of fairy godmother, jealous stepsister and Cinderella all at once. Each influencer’s story is carefully crafted as a personal epiphany, one they repeat and repeat to a growing audience. Social media is structured to reward the most flattened narratives and numbers are heady so you soon begin to believe the Ted Talk version of yourself. Until someone remakes themselves as a new improved latest iPhone model version of you. That someone is often a jealous stepsister cast out of the system who craves belonging enough to blot out scruples, whose covetousness gives them the drive to take your story for themselves and make it bigger.

Then you are trapped, a digital scream competing to be heard in a hall of mirrors. The show does a good job of showing how this narrative plays out with the larger structure of a world built by Silicon Valley dudes, selling you the snake oil of anyone can make it, if they’ve got a story to sell.

The show is more muddled in how it deals with the gobbledygook around wellness. It acknowledges the rising incidence of sickness and the crushing cost and inaccessibility of healthcare. It even alludes to how the clinical system can’t cope with the emotional aspects of illness. Each of us feels incredibly alone in a fragmented world, even if we have loving families and financial support. So we reach for a fairy tale where we can be seen as a whole self, a cure for the affliction of living in late capitalism, especially as a white woman who imagines herself in a fairy tale.

Inside all this there is though, an uneasy creep towards painting all non-Western medicine as fraudulent. Similarly, despite its layered storytelling which brings complexity, and a certain compassion with which it encases the individual stories, so you understand some unforgivable behaviour, there is also this hard to shake feeling that these kinds of shows are cautionary tales for women. Much like older tales in which girls who follow their sexual desires, their appetite for fame, come to a bade end. Just that here (as in most of life) sex has been replaced by money. Cam girls become Scam Girls. Unlike stories of male con artists which are always a little jaunty, giving us a little time to marvel at their chutzpah, their cuteness Scam Girls are always a mess, their mascara running, their lipstick smudging more with each scene. In Apple Cider Vinegar, one cannot help notice that the girl who is rewarded with life and wholeness is the one who returns to fold after an affair with ayahuasca and the badlands of social media to her good man, with a mainstream media job and the good Western medical system.

Well, everyone has a story to sell.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at paromita.vohra @mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!