If the web-series is indeed the new novel, then history as narrative non-fiction got seriously interesting for everyone

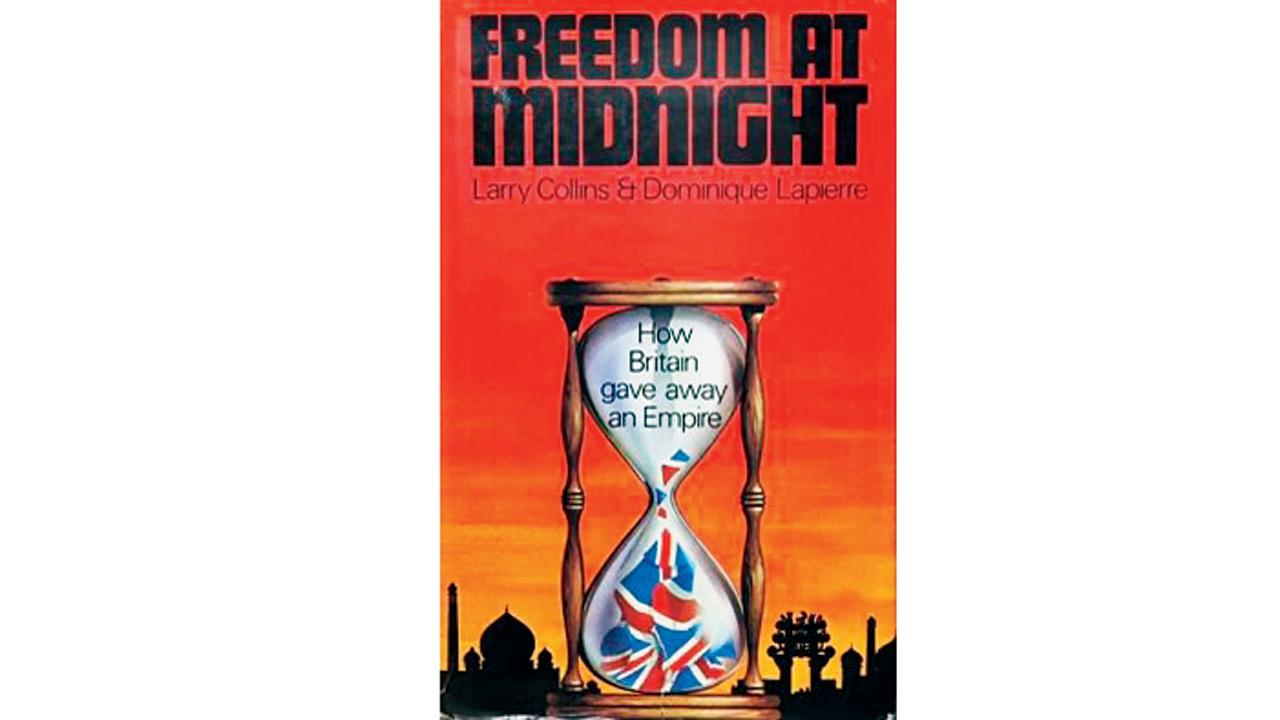

A still from Freedom At Midnight, an adaptation of the book of the same name by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre

First off: Sony LIV series, Freedom At Midnight (FAM)—based on Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre’s gigantic bestseller of the same name—is currently the most important work on India, by Indians.

First off: Sony LIV series, Freedom At Midnight (FAM)—based on Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre’s gigantic bestseller of the same name—is currently the most important work on India, by Indians.

ADVERTISEMENT

Given the piercingly researched, strikingly visual source-material, it was always meant to be.

No judgement on genres. What surprised me is the director to helm this grand historical narrative—about the transfer of power, from the British Crown to India’s democracy—is Nikkhil Advani, 53.

He debuted with the romcom, Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003). His last film was the insane John Abraham actioner, Vedaa (2024). FAM, with Advani, was unexpected. “But it’s unconscious,” he tells me, about such switch in genres.

Nikkhil Advani

Advani was at the success party of Rocket Boys (RB), that he’s the credited creator for.

That’s also a first-rate Sony LIV show; on the life of post-Independence scientific institution builders, Homi Bhabha, Vikram Sarabhai, and the reason Advani sufficiently credits RB’s writer-director, Abhay Pannu, for FAM.

At the party, Danish Khan and Saugata Mukherjee, Sony LIV’s content bosses, asked Advani, “So, what next?” He said, “Next glass of wine,” what else. Danish specifically meant to offer FAM, that he’d been eyeing to bring to screen since 2018.

What do RB and FAM have in common? Jawaharlal Nehru. So central to both the story of India’s Independence, and the new nation-state’s keenness in championing scientific temperament at a policy level.

The Nehru from RB (Rajit Kapur), though, “who’s PM, with nothing to prove,” as Advani puts it, you can see, is feisty and super-cool.

Nehru in FAM (Sidhant Gupta), PM-designate, appears perennially morose, over communal riots, and the impending Partition. To the extent that the performance itself feels a bit dull/one-note, as a result.

The Sony LIV series’ director

Unlike the fiery go-getter, Arif Zakaria, for Jinnah, totally standing apart. Opposite him, Mahatma Gandhi (Chirag Vohra), unwilling to budge from his principles; sickened by realpolitik, where the Congress, he feels, counts “laashein” (dead-bodies), and (electoral) “seatein”, alongside.

Sardar Patel (the brilliant Rajendra Chawla) is evidently the pragmatic politician, with “his feet on the ground”, balancing two ends.

Together, these men of history comprise hard negotiators of India’s freedom, chiefly with the sassy Lord Louis Mountbatten (Luke McGibney), the last British viceroy. Given the months leading up to the stroke of the midnight hour, August 15, 1947.

The movie-masala is all there in the book itself, that Collins and Lapierre finished in 1975. Starting in the early-’70s, only 25 years since Independence, with unprecedented personal access to Mountbatten, 72, who was a fan of their book, Is Paris Burning?

What followed were some kickass primary-source writing/reporting—over 800 kilos of documentation, 900 interview transcripts, plus historical archives—from Britain, India and Pakistan. Countries that the American and French author-duo had no personal stake in, of course.

A precious artefact that the authors showed to Mountbatten, from their research, was Jinnah’s X-ray, accessed from the doctor, which proved that Quaid-e-Azam (Great Leader) knew he suffered from advanced stage tuberculosis, and that he wouldn’t survive long; max, months.

Mountbatten told Lapierre-Collins if he knew this, he would’ve delayed the decision [on Partition], on which Muslim League’s Jinnah was resolutely adamant. Which, in turn, would’ve changed the course of sub-continent’s history.

Mountbatten (1900-1979) was himself killed in a terror attack by IRA (Irish Republican Army) militants, that I first learnt from FAM.

In fact, the BTS of FAM that the Padma Bhushan-awardee Lapierre (1931-2022) prefaced in a later edition of the book, dedicated to Collins (1929-2005), is good enough for a mini-film of its own!

Consider the authors regrouping the killers of Gandhi at Delhi’s Birla House to re-enact Mahatma’s assassination, for the camera.

A Sikh passerby walks in on them, presumably to attack. Except, that he takes the autograph of Gopal Godse, the assassin Nathuram’s brother, instead.

Journalists Lapierre-Collins were truly rock-star writers for an Indian generation that grew up on the railway station AH Wheeler paperbacks—making history so palatably fun to inhale.

As director Advani wonders to me, and many must have as well—it’s surprising that FAM had never been filmed before.

You must search online for a semi-viral clip of filmmaker Ram Gopal Varma, during an interview, where he rattles off verbatim, from pure memory, over a 250-word passage from FAM, stunningly describing Calcutta, during the Partition riots. This is simply unfilmable, Varma concludes.

Also, FAM is packed with anecdotes, gossip, some of it potentially sensitive, if not scurrilous.

Advani says he chose to focus on events, which can’t be disputed, after all: “Direct Action Day, interim government (formation), Mountbatten’s ‘Operation Seduction’, Punjab/Rawalpindi (riots), Noakhali (riots), Tiwana...”

Tiwana being the head of Punjab state from Unionist Party, with outside support from Congress, forced to resign, given Muslim League, single largest party, toppled his government, breaking his party as well… Politics of 1946 = 2024, no?

As Lapierre-Collins saw it, FAM is essentially a Greek tragedy. Advani says, “Gandhi paid the ultimate price for what he was most against.” Partition, of course. The second season of FAM, like the book, he adds, will end with the Mahatma’s death.

Which is how Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982) starts. That, in my opinion, and we can debate this forever, remains still the greatest film on India, by a non-Indian, ever.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!