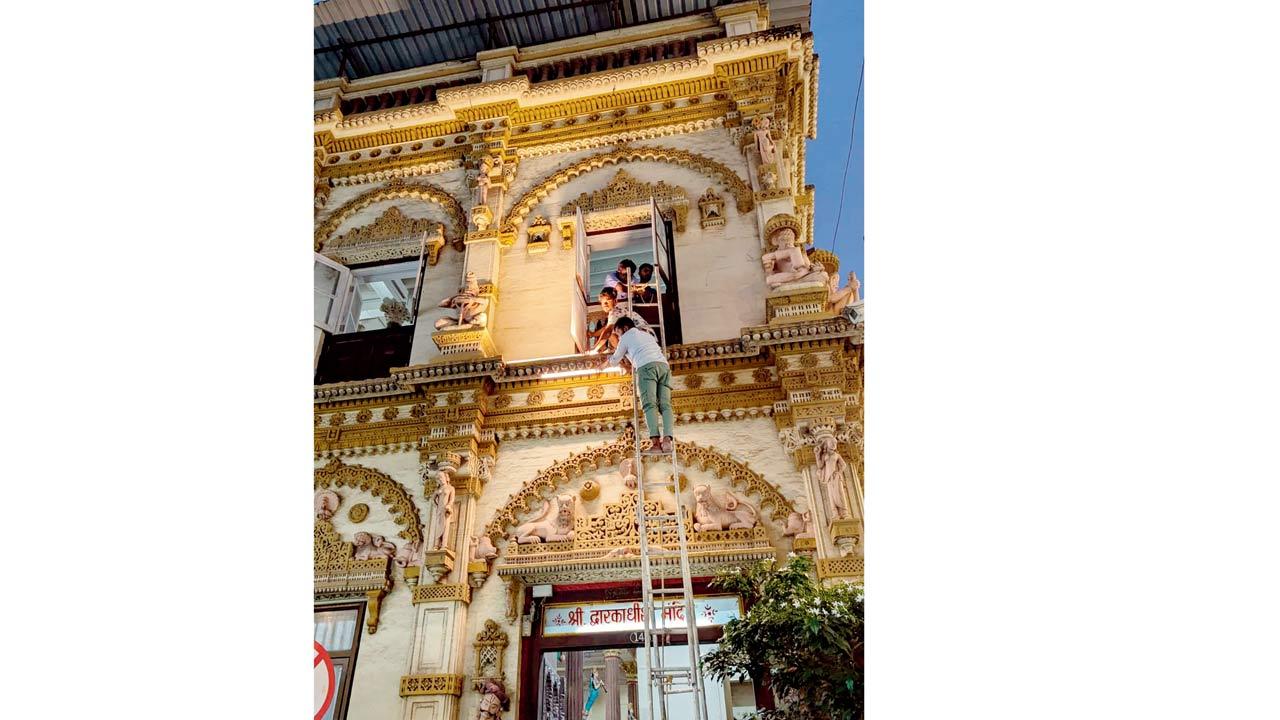

The restoration of the 1875-built Dwarkadhish temple in Kalbadevi resurrects a landmark haveli and the neighbourhood it graces

Architect Dhruti Vaidya on the first level of the restored temple. Pics/Atul Kamble

To think that a merchant’s unusual dream a century-and-a-half ago has resulted in a singularly unique architectural and spiritual haven.

To think that a merchant’s unusual dream a century-and-a-half ago has resulted in a singularly unique architectural and spiritual haven.

Located oasis-like near Ramwadi and Vithalwadi on the bustling Kalbadevi Road, the Dwarkadhish Temple, or Soonderbagh Temple, is possibly the oldest still standing and functional haveli structure the city is fortunate to have.

ADVERTISEMENT

The frontage of this Krishna-dedicated landmark is strikingly ornamented with sculpted figures, fruits and animals. Among them, carved rows of monkeys munching bananas made the British somewhat dismissively dub it the Monkey Temple.

View of the sanctum sanctorum

View of the sanctum sanctorum

An inscription etched on the main entrance, reads “This temple is built by Soonderdas, son of Thakar Mulji Jetha and dedicated to God Dwarkanathji in June 1875”.

Seth Mooljee Jaitha (as the family prefers the name spelt) was one of Bombay’s most eminent cloth traders. The hope and vision which led his son to gift the community and city this temple makes a charming legend.

Mooljee is supposed to have reported a vivid dream he had one night. It turned out an interesting visitation, with far-reaching consequences. The merchant revealed how God indicated that his swaroop (idol) was lying somewhere hidden in their house. Being the faithful follower that he was, Mooljee searched frantically for the statue. Discovering it at last in a wooden box stored under the staircase. Filled with gratitude, he resolved he would build a haveli to honour the divine revelation which was his privilege to receive.

Headed by Mooljee’s son Soonderdas, the family introduced the temple in 1875 under a separate trust formed specifically for it. Just as Lord Krishna had been brought up in the chieftain Nandaraja’s palatial home with life’s choicest comforts, the idol too was appointed with gorgeous murals, chandeliers and paintings for his enjoyment.

Restoration team members at work. Pic/Dhruti Vaidya

Restoration team members at work. Pic/Dhruti Vaidya

Manish Jaitha, representing the family’s seventh generation, says, “My childhood recollection is of going there at the age of six or seven with my parents, Rajnikant and Asha Jaitha, and uncle and aunt, Krishnakant and Anuradha Jaitha. Personally, I got involved with the trust and the management of the temple around 10 years ago, as the earlier generation wanted.”

Having founded the Mooljee Jaitha Market in 1871, four years ahead of the temple, the Jaithas lived on Vithalwadi Road, in convenient proximity to the market where their textile business was centred. They bought a building on the main Kalbadevi Road as a new family home on this plot. Jaitha elaborates, “As the construction of the new house had not yet begun, the temple was intended to have pride of place in the more prominent location. So, it was constructed on Kalbadevi Road. The Jaithas continued to stay in the original Vithalwadi Road house till the early 1900s, when they moved to Nepean Sea Road.”

Manish Jaitha’s grandmother, along with old family friends who were visitors to their Vithalwadi house, related stories of a bustling past. The narratives described how the entire vicinity was occupied by the homes and offices of textile traders conducting brisk business in the Mooljee Jaitha Market, where they held the majority of their stocks. The temple then served not only as a place of worship but was also a vital meeting spot where locals had an opportunity to interact socially with others from the neighbourhood.

Scene around the Dwarkadhish temple corner in Kalbadevi, circa 1890. Pic Courtesy Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Scene around the Dwarkadhish temple corner in Kalbadevi, circa 1890. Pic Courtesy Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“To the best of my knowledge, there hasn’t been a major renovation like this, though over the years the temple was modified to suit requirements of the time,” Jaitha says. “In this 150th year, the family decided to restore the temple as close as possible to its original state. This has been done so beautifully by Dhruti Vaidya and her team.”

Vaidya and her associate architect Vijay Panchal kept squarely in mind that this much-visited temple should have plans for its holistic restoration evolve such that devotees could continue to use the temple throughout the work period. “I’ve done many restorations, but no public buildings in Mumbai. This was special, being a place of worship but an urban building as well. Practical aspects, like waterproofing, plumbing and sanitation were sorted out—more often done from scratch—before getting to satisfying aesthetics. My office conducted detailed physical surveys, architectural and photographic, besides researching the history of the precinct. We enjoyed making the drawings.”

Though overpainted teakwood pillars, doors and balconies necessitated a thorough scraping, Vaidya has stuck to the basic colour palette, only freeing the overall ambience from pinkish-red to fresher looking ivory expanses. Suspended in a slant, rose pink, green and teal saree-clad winged “parees” peer down, benignly blessing those treading the cool marble floor towards the garbha griha. Pointing to the columns rising Corinthian-style, Vaidya explains that any structure dating back to the pre-Independence era would naturally bear the influence of foreign elements like these.

Anil Chaddha touching up Soonderdas Jaitha’s portrait. Pic Courtesy Indian Art Studio

Anil Chaddha touching up Soonderdas Jaitha’s portrait. Pic Courtesy Indian Art Studio

The temple is situated in the inner heart of Kalbadevi, the core area chaotic with noisy traffic honking between hundreds of small business galas, gold jewellery shops, clothing stores, shuttered banks and video game parlours. And each building rests cheek by jowl, a bare couple of feet from the next.

The transformation she has wrought in the midst of this mess is gratifying for Vaidya, who says, “Stepping inside to see the smiles of welcome worn by the wooden parees is mesmerising. Their calm expressions prepare you for your moment with the spiritual. I feel really happy to be able to get pujaris and others from

the temple to see the building in a different light. Not merely as a place to work in, but an architecturally beautiful space. People from the vicinity recognise the love and passion poured into this restoration.”

The fruit seller outside actually mentioned to Vaidya’s associate, “Now the building looks so nice, I will also keep my cart and surroundings cleaner.” When I wend my way through the thick of haathgadis parked outside to chat with him, Kasif says, “My father Nasir bhai, who sat at this same stall before me, would have been excited to see the temple lit up in the evening. Sach mein kitna sunder dikhta hai shaam ko.”

Vaidya befriended many of the ladies who regularly come for seva, threading flower malas to adorn the idol. “I grew fond of their smiles and their devotion,” she says. I speak with one of them. Sangeeta Patwa says, “Roj seva karva anand thaay. Tamaara jeva lekhak mandir maatey lakhey tetlu saaru [It is a joy to serve daily like this. Journalists like you should keep writing about the temple].”

I assure her of a great early account. Historian Sharada Dwivedi has shared a translated excerpt from Acharya and Shingne’s 1889 Marathi work, Mumbaicha Vruttant: “There are two doors leading to the temple, one to the west and the other the north. On the western doorway are images of Riddhi-Siddhi with Ganesh and above them a large clock. On the north and west facades, rishis, milkmaids and monkeys are portrayed playing games. Sages perform penance, munis have japmalas or read pothis. Some have long jata [hair]. The carvings are all very beautiful.”

The account goes on to highlight how, facing the black crystal idol of Dwarkanathji, surrounded by takkyas, or bolsters, a little fountain plays on certain assigned occasions. Dressed in garments of kinkhwab, with turban-type headgear resembling that worn by Vallabhacharya-sect maharajas, the deity presents a serene countenance.

Commenting on the frames in the interior (watercolour scenes from Krishna’s life lining the left walls inside, oil on canvas Radha-Krishna depictions on the right), Anil Chaddha, of the Indian Art Studio, says, “We maintained a balance to retain these artworks’ authenticity while enhancing their visual appeal—a delicate line to tread in restoration. The age and condition of the paintings presented difficulties: faded colours, cracks and peeling layers, required careful cleaning and repair.”

A fourth-generation member of the enterprise with his brothers Sanjay and Rajesh, Chaddha relates how it is the passion to preserve history that helps them keep this professional legacy humming smooth, for more than a century after their great-grandfather Jairup Narayan Chaddha of Bhatinda started his painting and restoration work from the studio in 1917.

“Preserving the original textures when removing decades of dust and grime was a delicate task,” adds Anil Chaddha. “We had to ensure that good restoration materials used, like the Winsor Newton oil paints, were compatible with the original paint to prevent further damage. Environmental factors, like controlling humidity and light, needed to be managed to protect the paintings during the process.”

How does he view the rapidly transforming Kalbadevi landscape? “Change is inevitable.

But the neighbourhood has become much too crowded with new establishments springing up in every inch of space. Repairs or reconstruction of old buildings are done with the aesthetics and history of architectural structures compromised.”

Inside and out, the preponderance of musical imagery is exquisitely rendered. Numerous figures, both within and on the external walls guarded by the carved dvarapalas, hold instruments like the veena, tabla and cymbals.

If stones could speak, what wonderful stories every lovingly restored celestial being here would tell the world.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!