Say forest officials first charged them for “encroaching” on forestland, then “tricked” them into signing away land-rights claims in lieu of being freed from the charges

Wagholi village’s Community Forest Rights claim was rejected in 2018

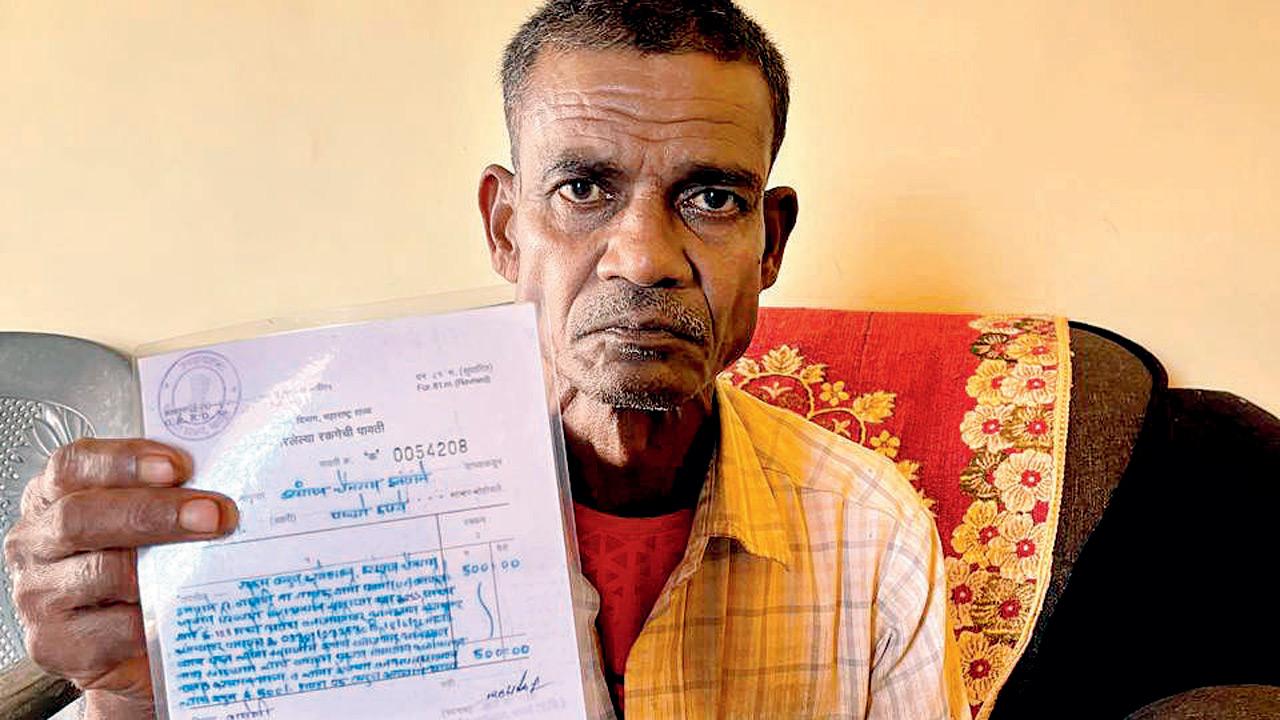

Paying a penalty is not a thing of pride. But in December 2022, Hansraj Chaitram Inwate, 62, a resident of Maharashtra’s Pench Tiger Reserve buffer zone, eagerly awaited a receipt against the fine imposed on him by the forest department for “encroaching” forestland. The Forest Range Officers of the Paoni buffer zone had told Hansraj that the fine receipt could serve as evidence of his occupation of the forestland, helping him secure rights over the land his family had cultivated for 35 years.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Forest Rights Act of 2006 (FRA) aims to grant titles of forestland and resource rights to forest-dwelling communities, if they prove occupancy or dependence on the forestland from before 2005. Claimants must provide at least two forms of evidence, such as village elders’ testimonies, public documents, government-authorised records, or traditional structures like wells and burial grounds. Encroachment fine receipts are also regarded valid evidence.

Hansraj Inwate with the encroachment receipt

More than two years later, Hansraj claims he had been misled. “I had no idea the document I signed stated we were voluntarily giving up our land rights claims. We have been fooled by the forest officials,” said Hansraj, who had 2 acres of land and five family members to support. However, forest department officials say the receipts were issued after confirming evidence of encroachment through Google imagery and verification from official sources.

Documents accessed by this correspondent revealed that at least 56 individuals across 16 villages under different group gram panchayats (when two or more villages are grouped under one gram panchayat) were made to sigh away their land rights.

Many villagers, including Hansraj, were in the process of filing land-rights claims under FRA in 2024. While they were collecting the requisite evidence, the forest department charged them for encroaching on the land and imposed a fine. The villagers paid the fine and signed the receipts thinking that these would validate their claims. Little did they know that the fine receipts declared that they “voluntarily abandoned” their claim to forest land in lieu of being freed from the encroachment charges.

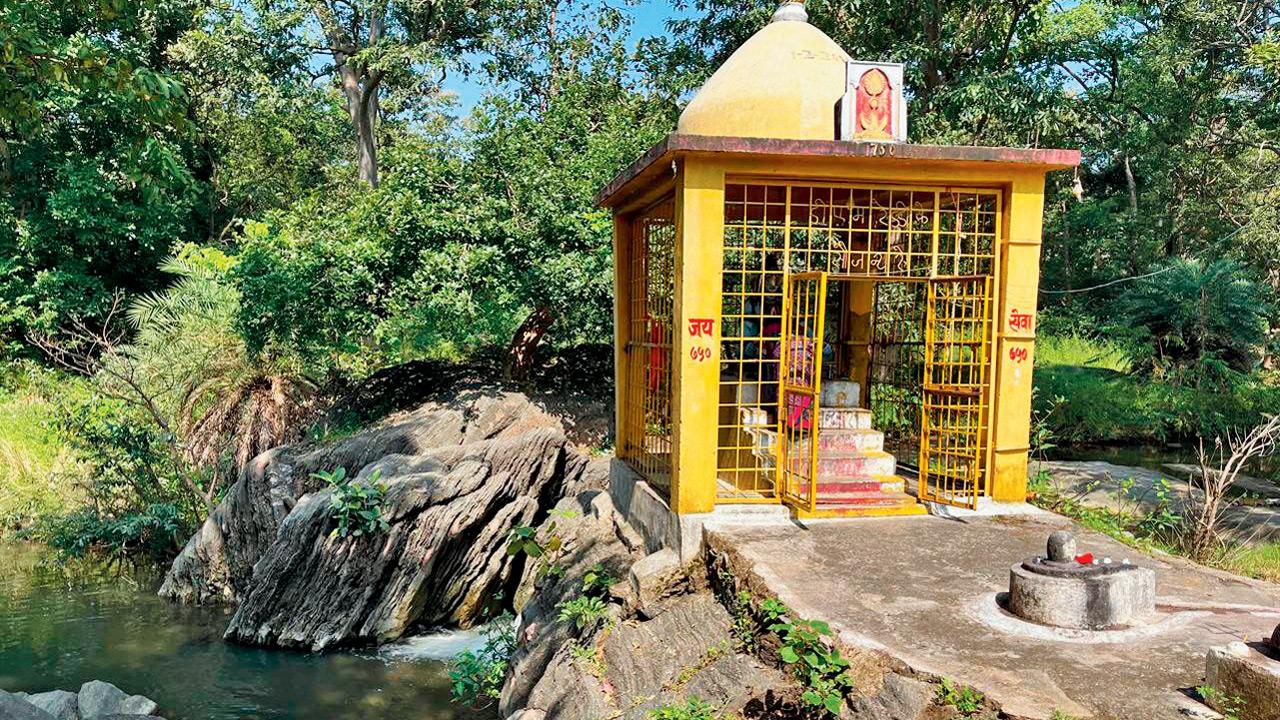

The temple’s walls bear the date ‘February 1, 2001’ as proof of longstanding use

The forest department’s ruse was discovered when Hansraj and a few others from the neighbouring villages went to the sarpanch of their group gram panchayat and found what was written on the fine receipt. At this point, they were left with no avenue to file the claims or access their lands. Hansraj who used to cultivate rice, cotton and toor dal (pigeon pea) was left with no source of livelihood.

In the next year and a half, some still tried to file claims and demanded titles from their respective sarpanches prompting the forest ranger’s office to issue a letter dated August 26, 2024, to six group gram panchayats. The letter stated that encroachment charges were issued and later dismissed after villagers “voluntarily abandoned” their land. The letter cited Section 66 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, which empowers officials to prevent encroachment.

Before the enactment of FRA, most tribals were considered encroachers on forestland even if they had lived inside the forest for generations. The 2006 law provides protection to tribals from such harassment by formally recognising their traditional land rights. In this case, however, the forest officials not only made a case of encroachment against tribals for the land they had claimed under FRA but used it to trick villagers into abandoning their claims.

“This kind of intervention by the forest department amounts to obstruction of the FRA recognition process. Such actions are illegal. These are constitutional rights that cannot be taken away arbitrarily,” said Tushar Dash, an independent FRA researcher, noting instances where a nearly identical approach was used to undermine the FRA.

Prabhu Nath Shukla, deputy conservator of forests and deputy director at Pench Tiger Reserve, denied the allegations. “We had to install pillars to demarcate the area under the forest department’s jurisdiction. Many villagers were unaware they were residing on our land. We will only act against those whose FRA claims have been rejected,” he said.

Struggles with FRA claims

While luxury tourism thrives in Pench Tiger Reserve’s buffer zone, promising opulence in the wilderness, villagers face an uncertain future. In 2015, Hansraj’s village, Wagholi, filed for Community Forest Rights (CFR) over 351.16 hectares of forest land. CFR grants local communities rights to collectively use, manage, and conserve forest resources like tendu leaves, mahua flowers, feedstock, and wild vegetables. Legal recognition was crucial to avoid future harassment by forest officials. CFR claims must be approved by the Gram Sabha, Sub-Divisional Level Committee (SDLC), and Divisional Level Committee before land titles are issued. In 2018, Wagholi’s CFR claim was rejected.

Notably, the village has a devasthan (temple) on forestland, which is included in the CFR claim. The temple’s walls bear the date ‘February 1, 2001’ as proof of longstanding use. However, the villagers had no idea that the temple’s existence could be used as proof to validate their CFR claims. “The tehsildar and SDO told us we didn’t submit the two required pieces of evidence. Even Gram Sabha members didn’t know how to handle the process,” said Praveen Uikey, sarpanch of the Pipariya group gram panchayat.

The locals then resolved to file Individual Forest Rights (IFR) claims using proper evidence but it took years due to a lack of awareness of the procedures. Most families occupied 1 to 3 acres of land. In 2022, when the forest department conducted their survey, around seven to eight families from Pipariya gram panchayat paid fines of R1000 each—R500 more than the stipulated amount—believing that it would serve as evidence for their claims. Hansraj’s receipt, written in Marathi, stated he “has built something on the forest land and hence, in order to be free of legal charges, he is agreeing to give up land rights and pay a nominal fine of Rs 500.”

Villagers fight back

Hansraj said, “I just wanted the recommendation from the forest range officer. If I was educated, I couldn’t have read and understood what was written in such small letters.” He has been trying to retract his statement for two years. Villagers claimed forest officials threatened to evict them if they continued cultivating land. They were also barred from collecting forest produce, leaving them without access to land or means to submit claims. Despite this, some attempted to file claims. The forest department’s August 2024 letter also stated, “encroachment holders are submitting forest rights claims to their respective Gram Panchayats. Such forest right claims should not be accepted.” The villagers’ plight reflects findings from a recent report by Call for Justice, an NGO, that highlighted widespread ignorance of FRA procedures.

Official Speak

Jayesh Tayade, Range Forest Officer, Paoni UC, said, “We have not issued encroachment receipts against those who have pending FRA claims. The receipts were signed following hearings, only after the villagers admitted to encroachment. The statement about ‘giving up land rights’ was a preventative measure under Section 66 of the Indian Forest Act 1927.” Section 66 of the Indian Forest Act 1927 gives the power to prevent the commission of offence (cutting down trees in a forest, setting fire to a forest, altering, moving, destroying, or defacing a forest boundary mark).

“The receipts were issued after confirming evidence of encroachment through Google imagery and verifying through Gram Sabha, SDO, and the collector if they had applied for the FRA or not. We believe they occupied the forest land territory in 2015-16, and not before 2005 as stipulated in the Act.

Many of these people already have 10-15 acres of cultivable land. They sometimes encroach on one or more acres in the forest area to acquire more and then ask for rights, but are unable to produce evidence. Why would they have paid the fine, if they didn’t believe they were encroachers?”

Tayade added that if the claimants have evidence to prove occupation they can approach him and he would assist them with the filing process. He also talked about how the villagers keep encroaching on the land after it is freed up and said that they are politically influenced.

The writer is from landconflictwatch.org, a data-research project that maps and analyses ongoing land conflicts in India

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!