There’s no doubt that the heritage walks mushrooming across the city are generating historical awareness among Mumbaikars, but can this translate to improved conservation efforts?

The historic CSMT is a popular stop on many heritage walks. File pic

I was looking for reasons to love my city,” says Pooja Barge, a marketing professional, when asked why she first started going for heritage walks.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Grant Road-resident has lived in the city all her life. But when friends began to move to other cities, her social life came to a stop. Her love-hate relationship with Mumbai began leaning towards hate owing to the rampant construction, heavy traffic, long commutes, and crowds. In an attempt to fix this, she pushed herself to step out for weekend activities. “That’s when I started attending heritage walks. And, it hit me like a tonne of bricks… I did not know my own city,” says Barge, “I didn’t even know my neighbourhood or what [historical events] took place 20 steps away from my house. Once I got all that information, I began to understand that there is so much history and there is logic and reasoning around why things are the way they are.”

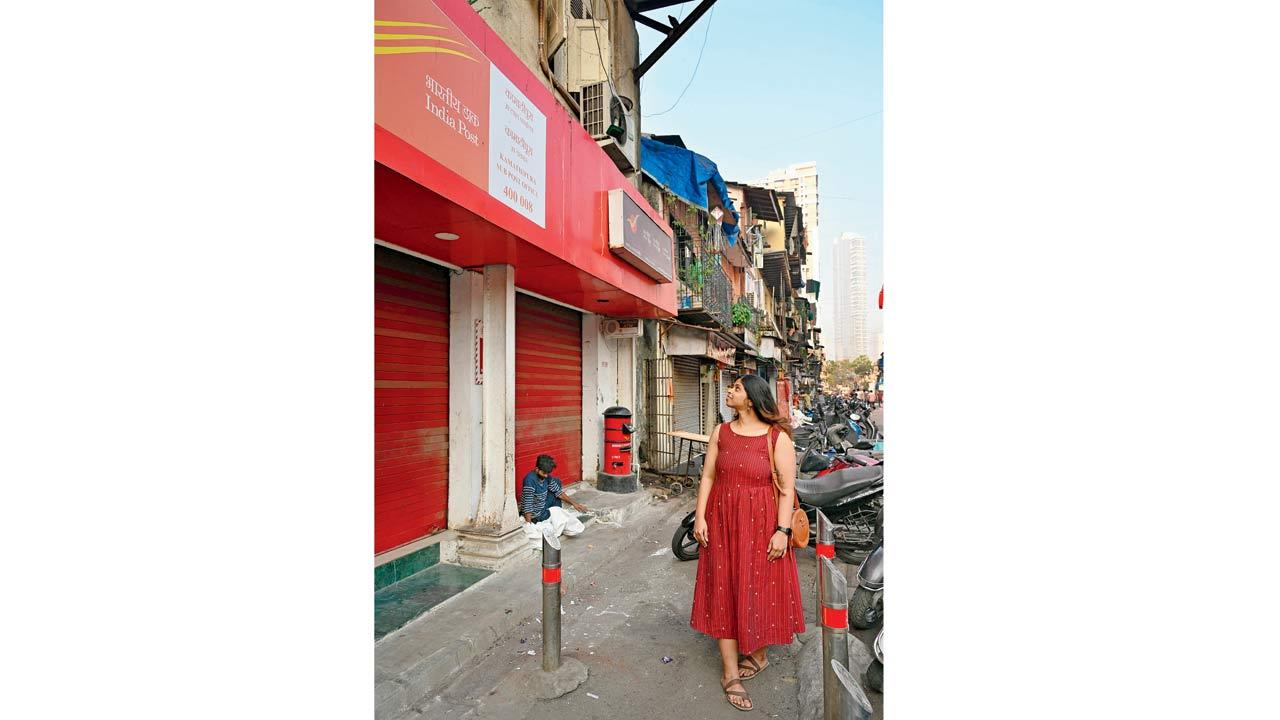

It was through Zoya Kathawala’s Beyond The Brothel Walk in Kamathipura that Barge discovered that the legendary anti-caste organisation, The Dalit Panthers was formed a few steps away from her home. And how special the Kamathipura Post Office is—it’s one of just 260 all-women post offices across the country.

It was on a walking tour that Pooja Barge learnt that the Kamathipura post office is among 260 all-women post offices across the country. Pic/Anurag Ahire

It was on a walking tour that Pooja Barge learnt that the Kamathipura post office is among 260 all-women post offices across the country. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Barge is not alone in her desire to learn more about the city. Increasingly, Mumbaikars are choosing to sacrifice their weekend morning sleep-in, instead setting out to gawk at historic buildings, hear the stories of the city and rediscover Mumbai. Whether one is interested in architecture, or city lore, there are several different walking tours that speak of the city’s history from different angles, from historic lanes and old bazaars to community experiences. The common thread amongst them is that they are backed by historical facts but are led by creative storytelling.

Building narrative around the city is what inspired Hashvardhan Tanwar and Eesha Singh to launch No Footprints, a touring company operating in Mumbai, Delhi, and Jaipur. During a walking tour in Paris, Tanwar was enthralled by the guide and her tales of the city. “The way that she was cracking jokes, and taking us around the city was incredible! Honestly, I was there to hate Parisians. But this one person suddenly made me see Paris in a different light. She became the ambassador for the city for me at the time. She made Paris a better city in my eyes,” he recalls.

In comparison, Tanwar found Mumbai’s heritage walks dry. He and Singh set out to change that with No Footprints. In Tanwar’s experience, most are not interested in lectures on history or facts about the country they are visiting. “Even if I go on a heritage walk for two or three hours, I’m still on a vacation, right?” he says. He adds that foreign tourists are more keen on engaging in India’s culture to understand why we are the way we are. However, he adds that the number of tourists coming into the country is not great. The World Economic Forum listed India 39th on the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2024.

Radha Goenka, Bharat Gothoskar and Hashvardhan Tanwar

Radha Goenka, Bharat Gothoskar and Hashvardhan Tanwar

Bharat Gothoskar, founder of Khaki Tours, a city tour company, agrees. “I had attended a few walks internationally, and in comparison, those in Mumbai usually focused on what style of architecture a structure has been built in, which the common man is not interested in. But if you tell people what happened in this building, and how it impacted the world, they are more likely to be interested,” he says.

The power of storytelling can be quite amazing. History books often tend to complicate the subject and focus mostly on dates and the chronology of events, which can be off-putting to many. A regular participant on many walks now, Barge agrees. “We are always taught about faraway places, not about our immediate city and neighbourhood. After attending heritage walks, I now have information on what happened 20 steps away from where I live. It’s an added perspective because I know why my neighbourhood is the way it is,” she says.

For example the juxtaposition of the well-maintained grand buildings with open courtyards along Grant Road—where the wealthy business-forward Parsi, Marwari, and Gujarati communities lived—with the decrepit, old theatres in the adjacent Kamathipura that were affordable for blue collar workers and sex workers who lived there. These theatres are steadily disappearing, with some downing shutters for good and others being razed for redevelopment.

A walk being conducted by Art Deco Mumbai. Pic Courtesy/Art Deco Trust

A walk being conducted by Art Deco Mumbai. Pic Courtesy/Art Deco Trust

As several companies and individuals now offer heritage tours in the city, it’s tough to put a number on how many walks are conducted every weekend. But tour hosts confirm that local participation has increased over the years.

“Pre-COVID, we had around 4,500 people walking with us on the streets of Mumbai in the entire year. Post-COVID, especially in the last financial year, 22,000 people walked with us. So the walking tour culture is definitely growing in the city,” says Gothoskar.

Between December and February is when this becomes most apparent, with the weather pleasant enough to lure AC-loving Mumbaikars out to explore the city.

A walk leader from Khaki Tours tells participants about the history of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai in Fort. Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

A walk leader from Khaki Tours tells participants about the history of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai in Fort. Pic/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Tanwar credits social media for this change. Post-COVID, he says, “The idea of walks to better understand your city suddenly blew up. A lot of people wanted to engage with culture, and it became a central conversation. Social media, too, gave a big, big push to such tours.”

While Gothoskar’s company sees an older audience in the 35-55 age group, Tanwar has observed younger folks—aged 25 and above—on their tours. He reasons that this is because “walks are a democratic way of being part of the conversation”. Plus, it’s not too rough on your pocket, he adds.

Some get their Mumbai history fix on social media, with creators such as Raunak Ramteke (@raunak_ramteke, 1.45 lakh followers) posting content ranging from where Bandra gets its name, to why the Mahim Police offer prayers annually at the Mahim Dargah. Besides, there are several accounts like Houses of Bandra, Houses of Chembur, Mumbai Heritage, among others that talk about city history.

The RPG Foundation and The Heritage Project conduct tours through Worli Koliwada, an 800-year-old urban village where they undertook a conservation and beautification project. Pic Courtesy/RPG Foundation

The RPG Foundation and The Heritage Project conduct tours through Worli Koliwada, an 800-year-old urban village where they undertook a conservation and beautification project. Pic Courtesy/RPG Foundation

All of this begs the question, though: Is this going to drive change and improve heritage conservation in the city? Atul Kumar, who founded Art Deco Mumbai in 2016 and was responsible for steering the campaign that gave Mumbai its third UNESCO World Heritage Site inscription, says that the walks are a lovely way to increase awareness, outreach, advocacy and engage with the younger generation. “We sometimes forget to ask this question: How is it driving change? But it’s not about statistical analysis; it’s all about reaching out. There are so many young people attending, and there is this wonderful access to these properties which have cultural and social relevance. Now, there are a variety of tours—a menu that offers something to everyone, depending on their level of interest,” he says.

As for the ethical implications of monetising these walks, Kumar says that can’t be judged. “It has to be viable,” he explains, “We [Art Deco Mumbai] straddle the other end, though, as we are not for profit. Our motivation is not profit, but engagement and sensitising people about where they live—so that they can make informed choices.”

Experts believe that increasing awareness among city residents will encourage them to preserve heritage structures when they come under threat. On this front, Ahmedabad shines as a beacon of hope. In 2017, it became the first city in India to get the UNESCO World Heritage City tag. But it took years of effort to get there, and it all started a heritage walk.

In the ’90s, conservation architect Debashish Nayak was invited there from Kolkata by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) and the civic body’s Heritage Conservation Committee (HCC), to aid the city’s efforts to preserve its history. Nayak’s very first recommendation was to launch a heritage walk. “If you want to restore or improve a city, you have to first make citizens appreciate their own context. I found that heritage walks are one of the best ways to make citizens appreciate their city,” he tells mid-day.

He had implemented a similar plan in Kolkata around 1985-86, and the popularity of the walks there assured him that it would work in Ahmedabad as well. In the mid-90s, he created Ahmedabad’s first-ever walk, titled “Mandir se Masjid tak”, in the old city area. The walking tour continues to this day, sharing the story of how Ahmedabad came to be, and how communities live in harmony. Seeing the programme’s success, the Centre requested the AMC to send Nayak to different cities across India, where he has designed over 80 heritage walks.

Conservation architect Vikas Dilawari, who has led restoration projects on some of the city’s most iconic structures, be it Flora Fountain or the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, cautions though, that awareness itself cannot be the endgame. “Heritage walks create citizen awareness, which is certainly a very positive thing. But we should also take things to the next step—citizen activism. People should point out if they see any tampering with historical buildings. Eventually, it should also lead to proactive conservation efforts by corporates and the government. This is how it works internationally,” he explains.

“You need to create this whole infrastructure,” agrees Nayak, who designed Ahmedabad’s heritage walk, and then added a guide training programme, a course in Heritage Management at the Ahmedabad University, and once even took 100 builders on a tour of the old town to inspire them.

The progression from citizen awareness to activism was seen most clearly in the efforts to preserve the legacy of 19th-century Gujarati poet Dalpatram Dahyabhai Travadi, says conservation architect and former director of the Ahmedabad Heritage Municipal Cell, Ashish Trambadia. “His house was largely destroyed as his family could not afford repairs. The residents of the city pooled in the funds to build his statue and commemorate him,” Trambadia says with pride. He explains that fortunately, in Ahmedabad, most heritage structures and the land around them are still inhabited, and their residents are therefore more inclined to maintain structures and repair them.

In contrast, Mumbai’s heritage buildings—whether they are inhabited or not—are at greater risk because of the high value of real estate, which often trumps the emotional value of a historical building. “Increased awareness among citizens is great, but it won’t translate to better conservation unless the decision-makers—owners of heritage structures, the users and developers—are also aware and think creatively on how they can preserve the historical value of a structure, such as retaining the exterior shell while repurposing the interiors. Instead, everyone talks about redevelopment because the amount of money involved is huge,” says a city conservationist, on condition of anonymity.

A feeling of community ownership is what the RPG Foundation’s The Heritage Project hopes to inculcate among Mumbaikars through their projects, such as the restoration of the Banganga tank and its adjacent steps. “First, we pick up sites or cultures that are not getting the attention they deserve. We research them well. We go and document the history of the place in the right way. Next, we build ways to preserve it,” says Radha Goenka, director of RPG Foundation and The Heritage Project (THP). Walks are a natural extension of historical conservation programmes, she says. THP is now also working on an app, Amble, which will allow people to take up walks on their own across different heritage sites and neighbourhoods in the city.

“We also get artists to come paint the area, and encourage the locals to pick up a brush and join in too. It’s almost a cultural revival. We have realised that to make all heritage preservation sustainable, we need to involve the community because it’s their site,” she adds.

Does this mean we will see fewer paan stains on monuments or historical neighbourhoods? Goenka says that’s why they involved the local residents in their Worli Koliwada conservation and beautification project. “It’s why we involved locals while painting murals and buildings in the neighbourhood. We want them to feel responsible,” she adds, hoping that these little steps will lead to some heritage consciousness. The Koliwada project also produced an off-shoot, Chefs of Koliwada, a cooking pop-up that provides an alternate source of income to the women of Worli Koliwada, giving them yet more incentive to support the initiative.

So, how much good can walking really do? Nayak cites an example from Ahmedabad: “A French ambassador had come for our heritage walk in 1999 and was very impressed. AMC and the French government signed an agreement, and they spent crores on several heritage projects,” he says, adding the clincher: “Heritage walks work like a catalyst.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!