What does the loss of a symbol mean for Uddhav Thackeray who is gearing up for the upcoming BMC polls, where he will fight against the rebel cadre and the BJP?

Illustration/Uday Mohite

The Shiv Sena versus Shiv Sena row reached its zenith this last week, when its original party symbol, the bow and arrow, which has been the kernel of its identity since 1989, was frozen by the Election Commission of India. A harried Uddhav Thackeray and his nemesis Eknath Shinde, whose now infamous coup led him to the seat of power in July this year, in a quick-fix sought alternatives that at least for the upcoming Andheri East bypoll will come to be associated with them. Where Thackeray’s party will contest under the name Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) and the symbol of the mashaal (flaming torch), Shinde’s Balasahebanchi Shiv Sena was allotted two swords and a shield.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The fact that the EC has recognised two Shiv Senas, changes everything,” says senior journalist Vaibhav Purandare, who has authored Bal Thackeray and The Rise of the Shiv Sena, “With this development, the party is officially split. Until now, Uddhav claimed that there was only one Shiv Sena, and that Shinde’s was a rebel faction. But he can no longer say that, and this complicates things.”

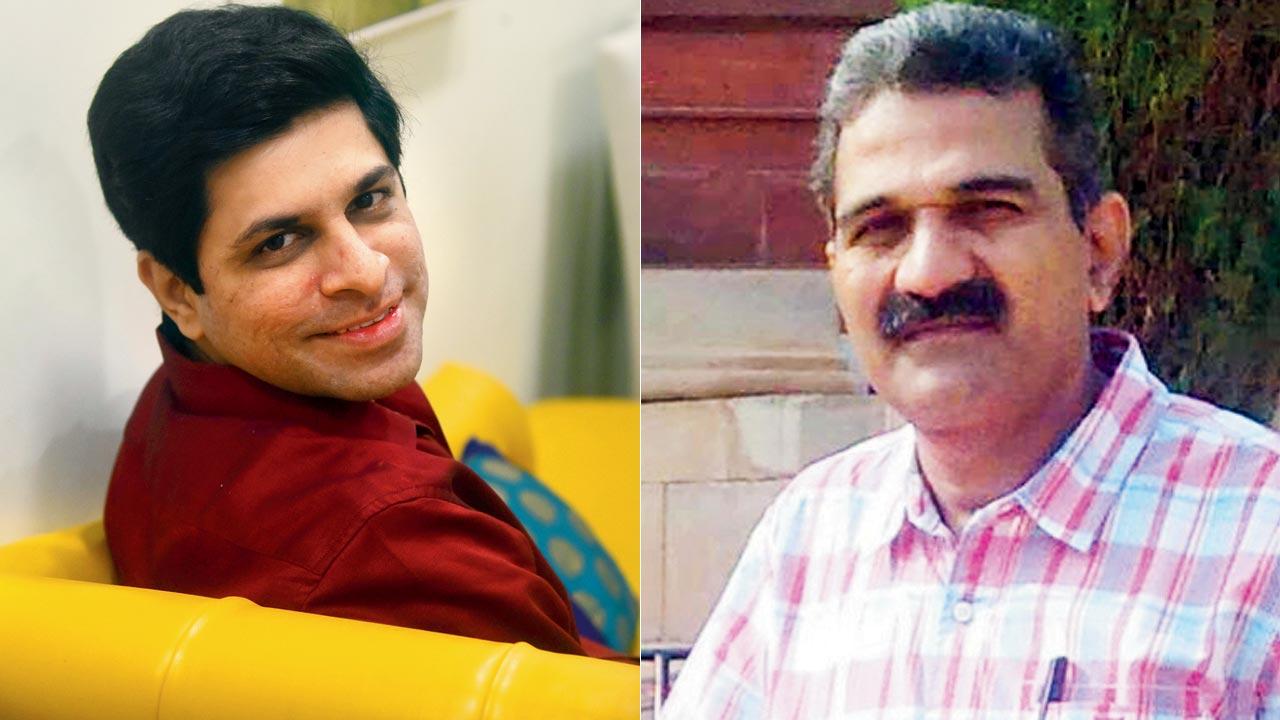

Vaibhav Purandare and Abhay Deshpande

Vaibhav Purandare and Abhay Deshpande

Most political experts and analysts are, however, divided on whether a symbol and name change, could mean a change in fortunes for either of the two.

According to Purandare, for the longest time, most parties didn’t even have a fixed symbol. “The EC’s rules have evolved over time. Initially, symbols were not given as much importance. It’s only when parties in India started growing in the 1970s, and the Opposition became stronger, that symbols became important. Because until then, the Congress was so dominant [in India’s political scene] that nobody could be bothered about anything else.”

Even the Shiv Sena, which was founded by Bal Thackeray in 1966, never leveraged a single party symbol in the initial polls that it contested. “It fought elections on various poll symbols... it has used a bat and ball, the rising sun, and even a mashaal,” says Purandare. In fact, it was the former Sena firebrand leader, Chhagan Bhujbal, who first used the flaming torch in 1985, winning a seat in the legislative assembly from the Mazagaon constituency. “That year, a number of other Sena leaders contested on various other symbols,” he says.

Santosh Pradhan, Jitendra Dixit and Shivam Shankar Singh

Santosh Pradhan, Jitendra Dixit and Shivam Shankar Singh

The Sena only got a permanent symbol three years later in 1989, after the EC asked parties to register themselves. Another senior journalist, who didn’t wish to be named, said that Subhash Desai was among the Sena leaders tasked with the job, and that’s how the party came to be allotted the bow and arrow.

Jitendra Dixit, West India Editor for ABP News, says that the “bow and arrow complemented Sena’s image of a militant Hindu organisation”. “In fact, the year that Sena was allotted the symbol, was also the year, when Sena electorally began pursuing Hindutva. It was the same year, during the bypoll in Vile Parle, when Bal Thackeray had made a venomous speech against the Muslims. Since then, Hindutva has become part of its political agenda,” adds Dixit, who has authored 35 Days: How Politics in Maharashtra Changed Forever in 2019. The bow and arrow is also associated with Lord Ram, says Dixit, adding that it became the perfect symbol to further their cause. As EC rules became stringent, the use of religious and animal symbols were banned. It’s why the Sena couldn’t use the roaring tiger symbol that it’s most associated with. That Shinde’s Sena bagged the more powerful name and symbol, which harks back to Maratha icon Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, makes the fight tougher for Uddhav. “Shinde couldn’t have asked for a better name,” thinks Purandare, adding, “All along, Shinde’s argument was that Uddhav had abandoned Balasaheb’s ideology and sided with the enemy [NCP and Congress].” Getting the name ‘Balasaheb’, which carries a lot of traction in the broader Maharashtrian population, now legitamises Shinde’s claim of being the true inheritor of Bal Thackeray’s legacy.

Having a fixed symbol has its advantages and disadvantages. “For starters, it becomes easier for the voter, in terms of identification,” says Purandare. “And when you are a committed voter, you are habituated to seeing the symbol and stamping [now punching] the symbol on the electronic voting machine.” The problem with a constantly changing symbol is that it can create confusion in the minds of the voter, especially if they are not adequately informed. “In India, literacy rates are still not very high... and in most rural pockets, voters cannot read the names of the party. They vote for the symbol,” adds Purandare.

Data analyst and campaign consultant Shivam Shankar Singh, says that with the kind of outreach possible today through social media, this problem has been successfully countered. Singh is the author of How to win an Indian election: What political parties don’t want you to know, and has headed campaigns for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for the Manipur and Tripura Legislative Assembly elections. “Of course, losing a symbol is not great news for the Shiv Sena. One has an emotional attachment with a symbol, and if anything, this episode has most likely affected the morale of party workers.” But modern communication now makes it possible to effortlessly and swiftly let the voter base know of the new party symbol. What, Singh thinks, has become clearer with the developments in Maharashtra is that the anti-defection law is now failing in the country. “It’s now only left to the courts to uphold the rights.”

Purandare says that irrespective, a symbol will have limited use if a party leadership is not strong. “A strong party leader would have a large following, and this translates into being able to communicate better about any new development, be it the change in name or party, to the followers and even the wider voter base.” He thinks that if the voter is convinced about the leadership, then party symbol is just tokenism.

In the case of the two Shiv Senas, however, Purandare feels that the symbol will play a crucial role, especially in the upcoming BMC elections, which has been Sena’s stronghold since 1997. The by-poll, he thinks, is going to be a litmus test for both the factions. “The BMC has an annual budget of almost R40,000 crore, which is more than the budget of most small states in the country. It makes it the most important election for the Sena, which has controlled it for three decades. More so now, in view of existential crisis because if it loses BMC, it loses its stronghold Mumbai and its main source of power. I remember doing the math for the previous BMC elections, and I noticed, more than 60 seats could have swung either way... and due to a difference of 50 to 100 [votes]. In such a scenario, if 50 of your voters put the vote in the wrong place [because of symbol], you’ve had it.”

Dixit feels that BJP has the biggest advantage in the upcoming BMC polls. “The current crisis has made things easier for the BJP. In the 2017 BMC elections, when Sena and BJP contested separately, the BJP was only two seats behind Sena [the latter got 84 seats, while BJP got 82]. BJP could have easily instated its mayor, but I think it bent backwards, because it had the Assembly and Lok Sabha elections in mind, where the two were fighting it out together. This election is hence, going to be very interesting.”

Not everyone thinks that Thackeray and Co. will have it tough. Political analyst Abhay Deshpande feels that Thackeray has the sympathy votes. “He has been cornered, and how,” he says. “In dynasty politics, it’s very difficult to de-link the family from the party. We are seeing this with the Congress too... Shiv Sena has always been a one-man army. Delinking the party from Matoshree and Thackeray is not going to be an easy task. Yes, they have suffered a big setback, after losing most of their MLAs and MPs, but they have regained some ground in the last two months. The numbers are less, but the spirit is high.”

Santosh Pradhan, political editor of leading Marathi daily Loksatta, agrees.

“There is a lot of sympathy for Uddhav Thackeray at present.” The fact that Thackeray had to move the Bombay High Court to get the BMC to accept the resignation of Rutuja Latke, the party’s candidate for the Andheri (East) Assembly bypoll, and the corruption charges against party’s leaders, has led many to feel strongly for the leader, he shares. “But, there’s also a huge anti-incumbency factor that’s going to come into play. So, it will be a tough fight. I think what happens in the bypoll is going to influence the BMC elections,” says Pradhan, adding “If Thackeray wins this, his party cadre’s confidence will definitely be high.” Deshpande says, “If they lose, the next two years will be crucial in determining the Sena’s fate.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!