In his new book, London-born chef Farokh Talati draws radial lines and orbs between his European training, Gujarati ingredients and Persian kitchen practices to spin a web where he comes home for dinner

Patra ni macchi in the making. A favourite at community weddings, the fresh fish coated with tangy coriander-coconut chutney and steamed in stringed banana leaf, Talati calls, “the best present anyone could receive at the dinner table”. ALL PICS COURTESY/OLIVER CHANARIN, SAM A HARRIS; BLOOMSBURY ABSOLUTE

London's oldest patisserie that has seen two World Wars has understandably a fascinating story waiting at every turn of its poetically whimsical interiors crammed with shelves of strawberry tarts, chocolate eclairs and choux pastry. Maison Bertaux’s original owners, the Bertaux family, were Communards who fled France after the Franco-Prussian War. The Vignauds were next, and then came Soho’s nonpareil Michelle Wade, who bizarrely started out at this coffee house as a teenager doing a Saturday job while training to be an actress at RADA. Taking a loan to buy the basement-plus-two structure on Greek Street because she couldn’t bear to see it shutter in the 1980s, Wade has kept Soho’s little sugary French gem going.

ADVERTISEMENT

One of the stories that sits ensconced in its poky basement has to do with a hit Parsi Curry Night. Its creator, chef Farokh Talati was led down the narrow flight of stairs by Wade who was keen to do something special where the baking area of the establishment originally stood in 1871 when it opened doors.

Talati remembers this as a time of trepidation and excitement. “What would people tasting food that they would only otherwise find four-and-a-half thousand miles away, say? But I know how exciting Parsi food is, there’s nothing quite like it. If you serve someone a good patra ni macchi, it will blow their mind. It was a lot of hard work. I’d cook the meal in a restaurant and ferry it halfway across London on the underground with pots and pans. I did everything—design the poster, email it to the guests, RSVP, cook and serve. It was exhausting but people loved it. First, it was for colleagues and friends. Then I saw the Parsis come, and I realised that it was working.

I thought, there can be a book, and this could be the audience for it,” he says in an interview over a video call. The pandemic was cruel to the future of the pop-up, but Talati has continued to actively let his cultural legacy tip-toe into his professional repertoire.

A meat pie he currently serves at St John Bread and Wine, a canteen-style dining room in Spitalfields, East London, gets its oomph from a 20-ingredient spice mix native to the Parsis, a tiny ethno-religious minority of India. The crusty-top pastry with filling may be Greco-Roman in origin, Egyptian even, but Talati’s version is gently and fully “Parsified”.

Derived from vinegar and jaggery, the sweet-sour flavour profile characteristic of the cuisine of the Zoroastrians in India, is celebrated on the menu of the restaurant that Talati leads, as is the love for offal. The pie’s filling uses dhansak masala and is cooked in much the same way his Dinaz aunty makes the aleti paleti, a liver and gizzards breakfast staple back in Gandhidham.

The pie, a version of which also finds a mention in his just-released book, Parsi: From Persia to Bombay (Recipes & Tales from the Ancient Culture) published by Bloomsbury Absolute, is Talati’s attempt to join the dots... from Persia of 7th century CE to Gandhidham of the 1960s and modern-day UK, the place of his birth.

His mother, Meher, moved to “dark and miserable” London in 1980 with his father Pheroze, who worked at the Wall’s factory in Southhall. Kidney pies and sausages that he’d lug back from the staff shop were quickly replaced with dar-chawal (dal-rice), tarkaari (vegetables), murghi and gos (meats). Talati, then in school, remembers choosing not to get out of bed until the aroma of sev (vermicelli) roasting in ghee wafted into his room on Navroze mornings.

Meher was possibly trying to keep the memories of her land alive through the kitchen, some from as far back as her childhood redolent with stories of summers spent in Deolali, waiting for the chaapat wala (pancake seller) to come by in the evenings, and lessons from her father, chief architect with Kandla Port Trust, on how to scale, gut and cook the ramas (salmon) into a coconut-coriander curry that her mother would occasionally perk up with a drumstick picked from the tree outside as it bubbled on a Primus stove.

It’s why Talati harbours a curiosity and pride for the food of his ancestors, evident in his debut book. I was personally delighted to find a recipe for tahdig (Persian scorched rice); Talati chooses jerdaloo ma gos as the flag bearer of the Persian influence that Parsi food continues to preserve in tiny ways. “The stew with dried fruits and the way in which the meat is braised on the bone, you can imagine it being in a Persian kitchen. But it uses masalas [Kashmiri chilli, cumin] we employ in India, to bring out the flavours.”

He first visited India at six, and returned repeatedly, landing in Mumbai before taking the train to Gujarat, where his mother’s family lives. But it wasn’t until 2013 that he arrived here with the resolve to document as richly as he could, eating as much as his appetite would allow. “When I, a chef cooking predominantly European-style food in London realised that it wasn’t the actual day-to-day work I was doing for 10 years, that was making me happy, but rustling up staff meals that invariably included a Parsi curry, I asked myself, why don’t I go down this road? I quit, travelled to India and learnt as much Parsi cooking as I could in three months,” he says.

The recent visits to Gujarat, one in 2019 and another in 2021 with friend and master photographer Oliver Chanarin, Talati calls “vital”. On a day trip to the Rann of Kutch with cousins, they made the customary stop at Khavda village in Bhuj, famous for burning buffalo milk for endless hours in cauldrons to produce golden-hewed mawa, the foundation of all mithai. Somewhere in the book, a young man looks into Chanarin’s camera expressionless, his left hand holding a ladle almost as tall as him, like a sceptre. On the next page, Talati offers you the option of making your own mawa which you know is a winner if when you drag your spoon across the bottom of the pan, it “parts like the Red Sea and slowly creeps back together”.

In Navsari, he visits the Kolah factory, the origin of every Parsi’s favourite sugarcane vinegar with a history going back to 1885. Mothers, including mine, speak reverentially of its triple spill-proof packing that successfully holds the burgundy liquid even when stuffed inside cabin baggage.

In London, Talati must make do with apple cider vinegar and Worcestershire sauce, which brings us to another curious British-Parsi culinary connection. The first of its kind Worchestershire sauce was invented in the early 19th century in the city of the same name by pharmacists John Wheeley Lea and Wiliam Perrins. The umami-flavoured sauce is to be found in every worthy Parsi pantry, making an appearance in their ‘cutlace’/cutlet (I reckon—or would like to believe—that the derivative comes from the fact that the Parsi cutlet has a trimming around the edges thanks to beaten egg, almost as delicate as the frill on the frock of little girls standing on stage for a picture at their navjote), chicken farcha and lagan no saas.

But it’s Udwada, the seaside sacred town housing the Iranshah fire temple, that Talati names as his favourite. “The craziness of life melts away there. The food is always delicious, and the people are welcoming and happy. I love the bhakras [sweet doughy tea time snack] sold opposite the fire temple; the masalas made by the husband-wife duo who hawk them from the back of their car; the ladies selling mint and papad in the alleys, and the doodh na puff [fresh milk froth], which vendors bring to your hotel door at the crack of dawn.”

We tell him we’d have liked to see more tales from the hinterland, those that justified the book’s title, and he smiles sagely over a hiccupping mobile network before remembering Dinaz aunty one more time: “The honest answer is that there could have been more of everything. My aunt, who just received a copy of the book in India, said, you took so many pictures and published only a handful!”

He isn’t, however, willing to pigeon-hole his reader. First timers getting acquainted with Parsi food; the young Zoroastrians growing up in the UK, US and Canada, and of course, India’s Parsis who may be adept in the kitchen, but keen to learn a hack or two from the expert—everyone is welcome to flip the pages of this imaginatively styled and impeccably produced title. We think he may have a point. Talati’s rigour is evident in the fine-drawn moves: cheering up the nankhatai dough with lemon zest; blitzing leftover mango achaar with an egg and drizzle of oil to make spiked mayo that goes wonderfully with fried chicken; and drawing out the flavours of saffron by infusing it in budget flavourless vodka and distilled water. But, he also, with equal earnestness, offers elementary guidance to novices on how to crack a coconut, make maska from scratch, bargain for mangoes at Crawford Market (“circle, touch, smell, haggle”), and where to find the city’s best buns—at Yazdani Restaurant & Bakery (my personal second favourite is Dhobi Talao’s Paris Bakery, where they are plump, light and stow away juicy black raisins, not cheap kishmish or tutti frutti).

The dinner pop-up may have wound up when COVID struck, and staff shortage after the lockdowns haven’t allowed him time to dabble in the part-time joy again. But this time, Talati might be thinking long-term. “Wouldn’t it be exciting for London to have its own Parsi restaurant?” he asks. With the shuttering of Mumbai chef Cyrus Todiwala and wife Pervin’s Cafe Spice Namaste, which Talati claims hit a roadblock due to rental issues, and Shamil and Kavi Thakrar’s Dishoom chain being more an ode to the city’s Irani cafes, he thinks London’s appetite for new flavours could support his dream. “It will be an honour to open London’s first proper Parsi restaurant. The rent is prohibitive, yes... how on earth to afford it? Staffing, rates, gas and electricity prices, and the complications that Brexit has brought with it are prohibitive. The only thing with you is people who will enjoy the food.”

I tell him this isn’t very different from Mumbai where hospitality entrepreneurs, both experienced and new, are struggling with high rents and scant staff. “So many iconic establishments have shuttered,” I say. “And K Rustom? Has it too?” he asks gingerly. Talati’s book carries a frozen pistachio dessert recipe inspired by the ice cream bars wedged between crispy wafers sold at Churchgate’s K Rustom’s & Company since 1953 that generations of Mumbaikars have enjoyed, including the Talatis.

On the night before I typed this story, my car turned from Marine Drive’s Pizza by the Bay onto Veer Nariman Road, once the address of sundry legendary eateries. On the other side, past the road divider, a small crowd of about 40 spilled onto the footpath and street outside North Stand Building of Brabourne Stadium. They were waiting their turn to get a foot into K Rustom for an after dinner-ice cream wafer sandwich which Khodabux Rustom Irani first hawked from what was once a department store. Talati needn’t worry, at least for now.

Adu Lasan Ni Murgi (Roast Chicken with Ginger and Garlic)

Give your Sunday roast a Parsi twist with this simple—yet rewarding—one tray wonder that’s certain to impress family and friends alike | Serves 6-8

Ingredients:

6 medium potatoes, peeled and quartered

1 large chicken (divided into pieces on the bone)

4 tbsp ghee or vegetable oil, plus extra for brushing

1 large onion, thinly sliced

4 tbsp ginger-garlic paste

3 small green chillies, split

2 whole star anise

1/2 tsp cloves

1 tsp cardamom pods, cracked in pestle and mortar

7.5 cm cassia bark or cinnamon stick

1 tbsp garam masala

1 tbsp jaggery

70 ml apple cider vinegar

1 litre hot chicken stock

Salt and freshly cracked pepper

Method:

Bring a large saucepan of salted water to the boil over a high heat. Add the potatoes and boil for 8-10 minutes, until tender but not falling apart. Drain and set aside.

Sprinkle the chicken pieces all over with salt. Spoon the ghee or oil into a sturdy baking tray or cast iron pot and place it over high heat. Fry the chicken pieces for about 4 minutes, turning regularly to give a golden colour all over the skin and flesh.

Remove the chicken pieces from the tray or pot and reduce the heat to low. Add the onion, ginger-garlic paste, chillies, all the whole spices, the garam masala and a good sprinkling of salt. Cook gently for a good 10 minutes, until the onion has softened and is beginning to turn light brown. During this time the ginger-garlic paste will start to catch in the tray or pot and darken—this is a good thing. Add a few tablespoons of water over the caught areas and scrape them free. The water will evaporate and the process will start again—repeating it over the 10 minutes will add an aromatic and caramelised depth to the dish. Preheat the oven to 190/170 degrees C fan. Add the jaggery and vinegar to the tray or pot, squashing the jaggery down with the back of your spoon to break it apart and help it dissolve.

Return the chicken pieces to the pan and nestle the potatoes around them. Pour the chicken stock over the top but do not submerge the meat or potatoes (think chicken icebergs poking above a sea of stock). For spectacularly golden potatoes, brush the parts poking above the stock with oil or ghee and finish the tray with a final flourish of salt and a generous crack of black pepper. Bake, uncovered, for 1.5 hours, or until the chicken is cooked through. Serve with kachuber (onion-tomato-cucumber-mint salad), wedges of lemon, and some cooling bowls of yoghurt.

Extracted with permission from Parsi: From Persia to Bombay (Recipes & Tales from the Ancient Culture; Rs 2,099)

Farokh’s favourites

From the book

Dhansakh masala. It displays versatility in the kitchen and allows you to experiment with your own food and cuisine, using it. I use it in curry pastes, lentils, I even added it to my noodles last night. You can use it to follow recipes from the book but also to channel your own creativity.

A recipe he cooks

Papeta ma gos. I love it. I make it quite a bit; it’s always a crowd pleaser.

He doesn’t leave Mumbai without

A visit to Ballard Estate’s Britannia & Co. The last one was in 2021 with Oliver and it was exceptional. A part of me was worried whether the impact of the COVID lockdowns and Boman Kohinoor’s passing, had affected things. And, the ‘dhai’ (yoghurt) at K Rustom is outstanding. May I also include the dal ni pori and patrel at Perviz Hall in Dadar? How can you give a standout food recommendation in India! Everything is tasty.

Farokh Talati with Rascal

A staffer at a confectionary shop in Khavda, Bhuj district, famed for its mawa making

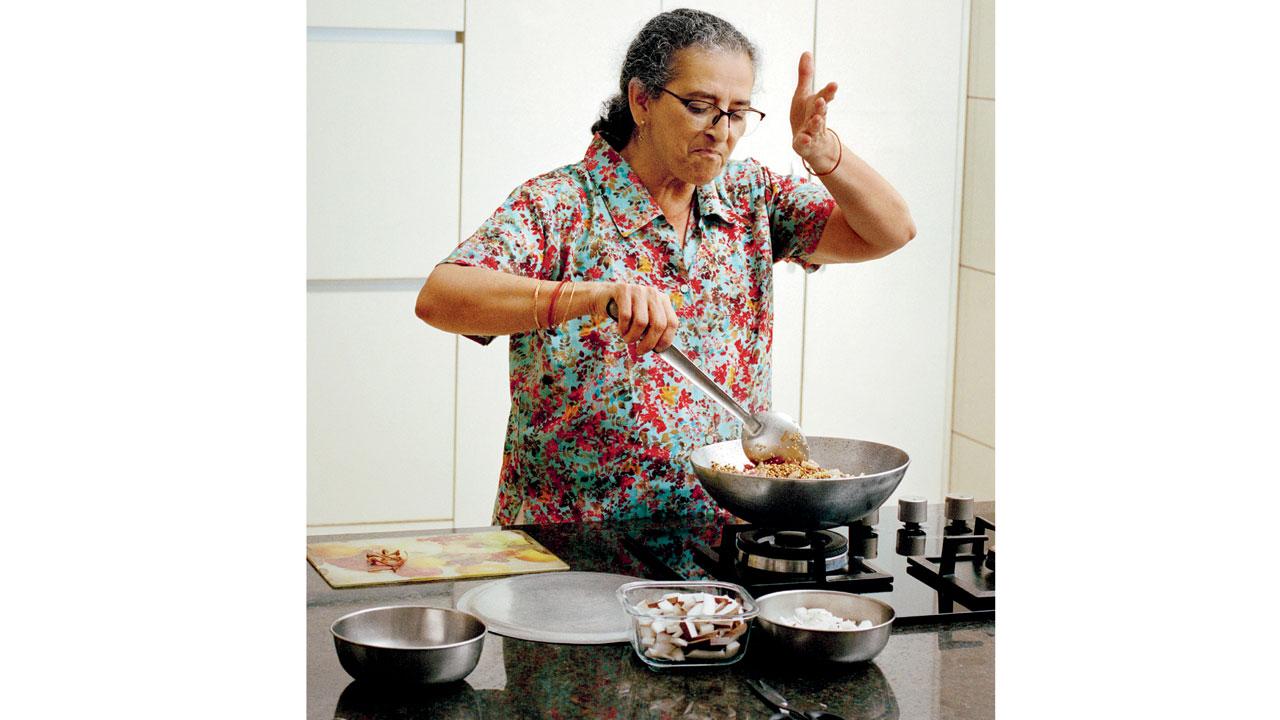

Talati’s aunt Dinaz in the kitchen of her Gandhidham residence making coconut and tamarind fish curry

Talati’s pistachio ice cream sandwich is a nod to Mumbai’s K Rustom & Company

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!