The fruit is no longer ‘exotic’ as chefs and street vendors embrace it equally. But is there a space for avocados from India on our plates?

Avocado thecha with batata papad

It first surfaced on toasts. Its health benefits were listed all over the internet. Then, tips on how to ripen it popped up. Memes followed. Soon enough, vendors in wet markets began selling a single piece for over R120. Avocados have been enjoying the spotlight for some years now. In 2017, avocado toasts flew from Australia to menus in the West and gradually to India. Almost everyone was eating one for breakfast (and still does).

ADVERTISEMENT

The exotic fruit continues to enjoy virality on social media and has a dedicated emoji. Now that it’s available on every other menu, it is the most expensive street food item. From simple avocado toasts to avocado sushi rolls (yes! street sushi for R250 in Kandivli), and even an avocado thecha vada pav (R150 for vada pav, really?), it’s everywhere. And it’s not going away anytime soon.

About a year ago, Kalakar, a sandwich stall in Surat, went viral for its R400 avocado toast. Soon after, Healthy Affair launched in Vadodara. “Avocado toast is popular for being tasty and healthy, but cafés here priced it too high,” says Himani Fadadu, co-founder of Healthy Affair. Offering classic guacamole toast on brown bread or sourdough for R150 (two slices), their street cart quickly went viral within two days of opening.

In Mumbai, Oh! Bambai, a vada pav eatery in Ghatkopar (now temporarily closed), adds avocado slices to their vada pav along with thecha. Meanwhile, in Andheri, Mewalal Pasta and Salads keeps it simple with a menu for college kids and gym-goers. “We started with salads to attract gym-goers, but customers began asking for avocado toast, so we added it,” says Vishal Gupta, who runs the roadside stall with his brother Vikas.

Despite avocados costing around R100 each, the fruit has gone from gourmet to gully. Street vendors say the demand justifies the price. “We use Hass ones from a local supplier, and prices have dropped slightly to R150-R180 per kilo,” says Fadadu, who once paid R200-R250 per kilo. Gupta, however, uses an Italian variety that costs him R590 a kilo.

The Hass avocado, grown in Mexico, Peru, the USA, and Australia dominates India’s market due to its consistency and rich, creamy texture. Known for high oil content (around 18 per cent), Hass is perfect for guacamole, salads, and sandwiches. Its pear-shaped body and rough skin transitions from green to black when ripe, encasing a smooth, bright green interior. “Most chefs have made it their favourite variety because, they ripen consistently and have a thick skin, reducing bruising,” say chefs Ebaani Tewari and Mathew Varghese of Kari Apla, Khar. Fadadu adds, “We tried using local varieties from Kodaikanal and Kerala, but they were too fibrous for smoothies and bruised easily, leading to more waste.”

Harsh Godha has imported over 18,000 plants and planted his first orchard of Ettinger variety, which began fruiting in just 18 months

In South India, varieties from Sri Lanka have been cultivated for decades, mainly on coffee estates, where locals call them “butter fruit”. However, their shape and taste differ significantly from the ones we commonly use today. “Butter fruit has always been available in Coorg, but nobody paid much attention to them as coffee was the focus. Now, growers sell to Bengaluru and Mysore,” explains Chef Naveen Alvares.

The Central Horticultural Experiment Station in Chettalli has experimented with over 30,000 varieties, successfully grafting the Arka Supreme and Arka Coorg Ravi for local farmers. Similarly, in Bhopal, Harshit Godha founded Indo Israel Avocado after craving the quality he enjoyed in the UK. “Whenever I came back to India, I would find poor quality avocados from Kodaikanal, which were very watery in texture,” he recalls. Frustrated, he pursued training in Israel, learning to grow Hass-like avocados in hot climates. By 2021, he had imported over 18,000 plants and planted his first orchard of the Ettinger variety, which began fruiting in just 18 months.

In Chikkamagaluru, Kerehaklu Plantation has been growing seven avocado varieties since the 1980s, supplying Choquette (buttery with notes of a custard apple) and Zutano (nutty flavour, like an almond) to local restaurants. However, Godha notes that Hass avocados are preferred for their post-harvest handling and long shelf life. Indian varieties may not enjoy a similar glamorous career abroad. Pranoy Thipaiah of Kerehaklu cites challenges in exporting Indian varieties to major cities, stating, “Producers are also unaware of how to handle the fruit. We have tree climbers, while some orchards shake the trees [to harvest the fruit], so they bruise.”

Owners and brothers Vikas Gupta (L) and Vishal Gupta (R) making avocado toast at their stall in Andheri East. PIC/SHADAB KHAN

So, is anyone eating the humble Indian avocado? Chefs in the South certainly are. “During the season, we use the Arka Coorg Ravi, which grows locally,” says Chef Prince J, executive chef of Evolve Back Chikkana Halli Estate, Coorg. The estate focuses on local produce, leading to innovative dishes such as avocado chutney, stuffed kulchas, savoury muffins, paniyaram, idli, and ice cream. “The Arka Coorg Ravi is round with a yellow-pale flush, and its pulp is rich in protein, making it ideal for Indian cuisine,” he adds. Chef Alvares, who incorporates Coorgi avocados into traditional dishes such as palya and moru curry, notes, “The beauty of Indian avocado is that it doesn’t fall until ripe, so when it does, it’s perfectly ready.”

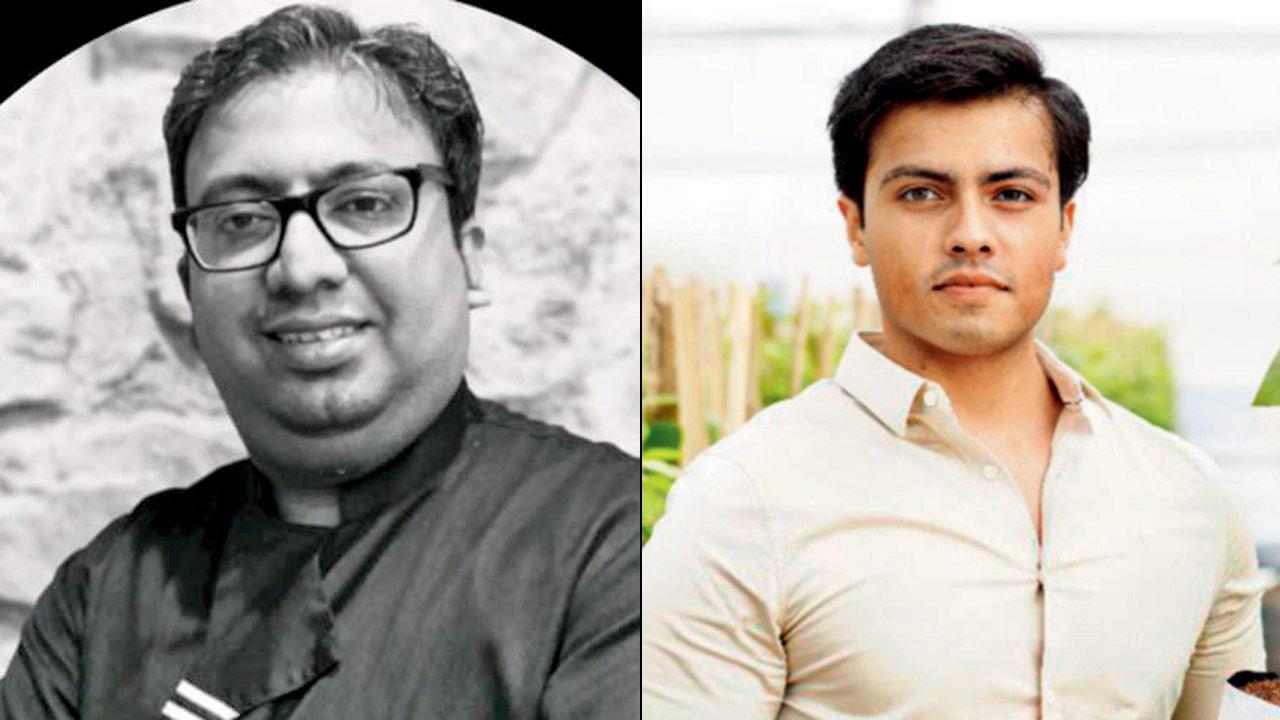

Ebaani Tewari and Mathew Varghese

However, the popular Hass variety also complements Indian cuisine, as seen in dishes like Kari Apla’s Purple Cabbage Koshimbir with Avocado and Avocado Thecha. Chefs Tiwari and Varghese explain, “We wanted to bring something fresh and exciting to our menu, and avocado fit the bill perfectly. It’s versatile and healthy, so we thought, why not give it a regional twist?”

Naveen Alvares and Harshit Godha

What will it take for Indian varieties to gain traction? Thipaiah suggests, “We must change the perception that they are inferior, [just] as we have elevated coffee and cacao. I understand chefs need consistency, so we must connect the dots.” With entrepreneurs such as Godha leading the way, there’s hope that Indian-grown avocados will become popular someday. “My farm is only 4.5 acres, but once we have larger-scale farms, the Indian industry will start receiving good quality avocados from reliable sources,” he concludes.

Rs 400

For an avocado toast at a street-stall in Surat

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!