As photos of a “deserted” Goa in peak tourist season go viral, we ask, is the dream of the affordable Goan holiday over?

Quite a few people told this paper that tourist footfall at Goa’s beaches and shacks have fallen drastically in the 2023-24 peak season. Representational Pic/Getty Images

If you had a budget of Rs 50,000 to R1 lakh for a seaside holiday for two, would you rather go to Goa or to an international destination such as Thailand, Sri Lanka or Vietnam for the same cost?

ADVERTISEMENT

For the value-minded Indian tourist, this is a big question. It’s also the question at the heart of the slugfest taking place for the last few weeks on social media, where photos and videos of “deserted” beaches and shacks in the sunshine state have gone viral. Some of these images were reportedly taken between Christmas and New Year’s Eve, during the state’s peak tourist season. The posts claimed “Goa tourism is dead”, blaming the reported fall in tourist footfall on exorbitant costs and the infamous taxi mafia. Quite a few Goan citizens have countered that the posts are merely fake news. The Goan government even filed a police complaint against an X user who had highlighted some statistics to indicate that tourism footfall was plummeting.

This photo posted by @DeepikaBhardwaj on X, which she says was clicked at Calangute close to New Year’s Eve, generated a lot of conversation about Goan tourism; (right) Shehnaz Treasury’s content often focuses on educating people on how to be better tourists, including this shoot from her anti-litter campaign

This photo posted by @DeepikaBhardwaj on X, which she says was clicked at Calangute close to New Year’s Eve, generated a lot of conversation about Goan tourism; (right) Shehnaz Treasury’s content often focuses on educating people on how to be better tourists, including this shoot from her anti-litter campaign

But is there any truth to it? “Very much so. We have been seeing fewer tourists out and about this year,” says Raj Saini, who owns villas in Cavelossim that he lets out mostly to long-stay tourists. “Because we have mostly repeat guests who book villas with us year after year for the three-month peak period [December to February], we didn’t really feel the impact. But business at shacks seems to be low this year,” he admits.

Is there any weight to tourists’ grouse that Goa has become “overpriced”? “Yes, the way I see it, Goa is getting costlier. International tourists have already been reducing for a few years, particularly since the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020. Mainly, they feel that South East Asian countries are cheaper and give them a better experience. Some Indians, too, now prefer to go there,” he shares.

Also Read: A conscious traveller’s guide to travel etiquette in Goa

Thalassa and Purple Martini are some of the more popular party spots in the state today. Pics/Instagram

Thalassa and Purple Martini are some of the more popular party spots in the state today. Pics/Instagram

The truth is, until now, Goa was a category apart—most Indians had few other options for holiday destinations that could offer Goa’s beaches, a rich cultural and food scene, as well as its famous nightlife. But with disposable income now rising among Indians, as well as visa regulations easing up in South East Asian countries, Goa no longer has a monopoly on the hearts of Indians dreaming of a beach holiday.

Tour organiser Prahlad Raj

(@prahladraj85) recently tweeted: “My clients prefer visiting Phuket, Krabi, Vietnam and Bali. Nobody enquires about Goa these days.”

It’s much the same among foreign tourists too, who first started coming to Goa in droves in the 1960s, back when the coastal state was an affordable haven for hippie backpackers. Aiden Freeborn, a British national who is Senior Editor at thebrokebackpacker.com, first arrived in Goa in 2016 and fell in love with its beaches, pocket-friendly shacks where one could sleep for just R300 a night, and its world famous nightlife and psytrance raves.

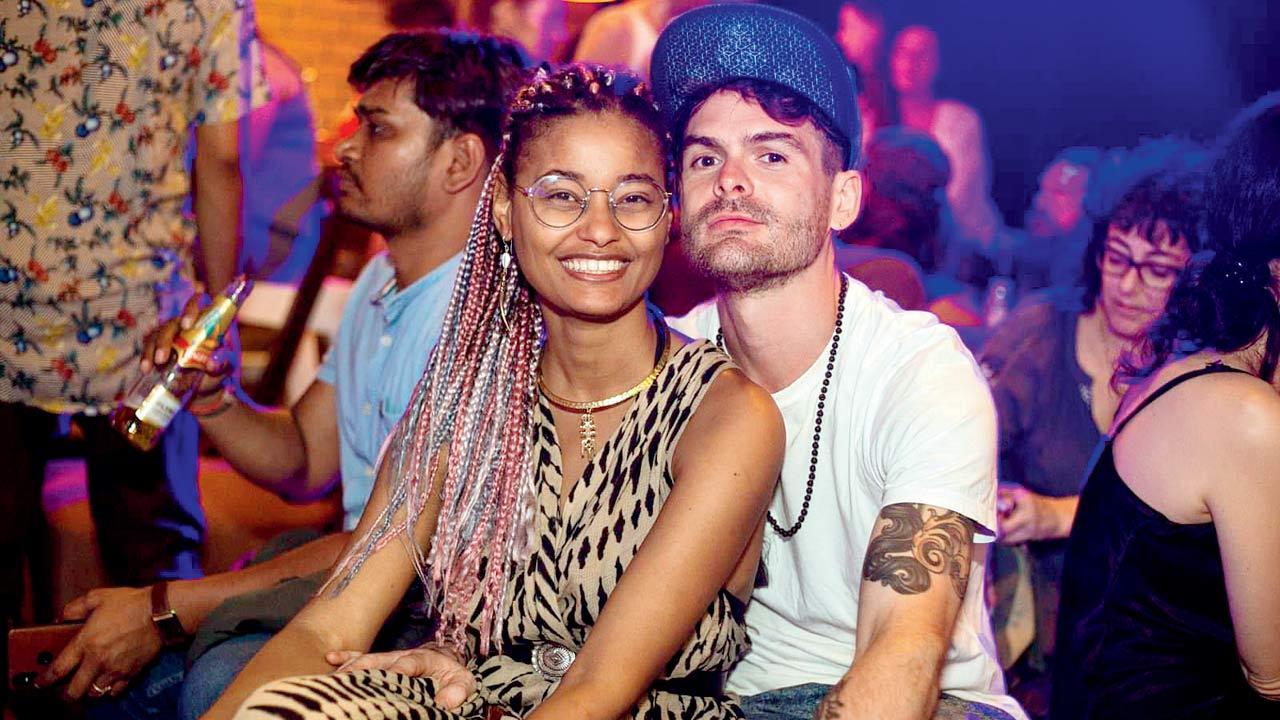

British national Aiden Freeborn and his partner at a party in Goa in 2022. In the late 2010s, he enjoyed the raves at venues such as Shiva Valley and Hilltop

British national Aiden Freeborn and his partner at a party in Goa in 2022. In the late 2010s, he enjoyed the raves at venues such as Shiva Valley and Hilltop

This season is the first time that he has not returned to Goa since then (apart from 2021, when COVID restrictions were still on for international travel). In December 2024, he posted on thebrokebackpacker.com, explaining why he can no longer recommend Goa to fellow backpackers: “Goa used to be a true budget backpacker destination where frugal travellers could get by on just a few dollars a day… Flash forward to 2024, though, and Goa is getting expensive… there are just better places to be right now.”

He recalls how in 2017, “we found a nice, simple, traditional Goan 2BHK house for R14,000 per month. By the end of 2022, we were paying Rs 25,000 for a 2BHK in some cases. All the houses we rented over the years were all between Arambol and Mandrem, and about half a kilometre from the beach.”

Goa is the birthplace of the now global psytrance subculture, known for its legendary outdoor raves. “The Psytrance scene circa 2016-18 was a bit of a golden period in my view. The parties were cheap to enter—except Hilltop—and the crowd was a mixture of proper psy-heads, backpackers and locals,” he tells mid-day over email.

Prashant Shintre, Shailendra Mehta, Shohail Furtado and Flexcia D’Souza

Prashant Shintre, Shailendra Mehta, Shohail Furtado and Flexcia D’Souza

He recalls how a concerted effort was made to strangle the Goan party culture, cracking down on the psytrance parties which were known to be peaceful, affordable and hardly ever a nuisance—there was no post-party litter, and events were always held in secluded areas to prevent disturbing locals.

While Goa now has plenty of clubs, they are all overpriced and “soulless”, says Freeborn, adding, “The parties these days play a lot more minimal techno at best, and generic EDM at worst. There are a lot of ‘influencer DJ’s’, the crowds are more uptight, the parties are expensive. Most venues are also indoors/under cover now which also changes the vibe.”

Now, foreign and Indian tourists alike head to places like Thailand to sample psytrance culture, such as the full-moon parties at Koh Phangan.

“I have no plans to go back anytime soon,” says Freeborn, “Although I will return one day to see how it has evolved. For now, it just doesn’t feel the same.”

Meanwhile, in the post-COVID years, as international tourist numbers slipped to all-time lows, Indian tourists who had been starved of all travel due to lockdowns began to head to Goa by the busloads in a phenomenon that has since been named “revenge travel”. In 2023, when foreign tourist footfall in Goa was around 4.5 lakh, domestic tourist numbers peaked to an all-time high of 80 lakh in 2023.

But this way more than the state’s infrastructure could handle, and Goan locals do not remember the previous season’s jam-packed beaches and streets fondly. Besides, the profile of visitors had changed too.

“Most tourists who come to Goa now are not big spenders,” says Shohail Furtado, a local youth activist, “They book AirBnbs and cook their own food. They mostly go to tourist spots to take pictures for Instagram and don’t spend at restaurants or on activities. So even if domestic tourist numbers are rising, has the revenue increased proportionately? The government should put out data on this.”

And what of the big spending tourists who seem to have switched to international travel instead? “They complain about a lack of infrastructure and it’s not false. We don’t have basic things like clean washrooms at most beaches, which is something you see at South East Asian destinations. We don’t have proper public transport,” he adds.

If the authorities want to drive tourism numbers up again, Furtado says, they must address these issues, as well as the one major grouse that Goans have been raising for a few years—the “Delhification” of Goa. Locals have time and again rued about an influx of drunken, rowdy tourists from north India who vandalise public property, litter, get into brawls and misbehave with women tourists. “The government must focus on law and order so we can fix the state’s reputation; we’ve been attracting the wrong sort of crowd lately,” says Furtado.

But some introspection is required too, the activist says: “I’d like us to take some blame upon ourselves as we’re not fighting hard enough to make the government implement these basic facilities and resources that we need to make us an attractive destination for the upper echelon of tourists. And, somehow, we’ve stopped promoting our own culture and endorsing the Bollywood image of Goa.”

It’s not just the Goan tourism industry and the stakeholders—including locals—who need to introspect, though. Indians’ reputation as “bad tourists” is now following them to their newly preferred destinations as well. On January 5, podcaster Ravi Handa posted from his X handle @ravihanda that he decided against Goa for his New Year break because of this influx of poorly behaved domestic tourists to the beachy state. He chose to go to Vietnam instead, but found the same problem there. “Even in Vietnam, the only bad behaviour was from North Indian tourists,” he tweeted, highlighting how he had seen them jumping queues and chanting “Bharat Mata ki Jai” on a train.

Some Goans—and long-time Goa loyalists—hope that this lull in tourism will serve as a reset for Goa. “I haven’t seen the rowdy tourists from recent years in Goa this year, and I am very happy about that. It’s nicer with fewer tourists. This is what Goa always used to be like years ago: Peaceful,” says actor and content creator Shehnaz Treasury, who splits her time between Mumbai and Goa.

She agrees that costs have risen quite a bit, and that the taxi mafia is a genuine problem. “Goa has become very expensive, be it hotels or taxis. Taking a taxi from one point to another in Goa might cost you more than more than your flight ticket. So if you don’t drive or ride a bike, you’re stuck in your hotel. Hotels, food, commute are definitely much cheaper in Sri Lanka, Vietnam and Thailand, which are giving Goa a run for its money,” she says.

Fellow digital creator Flexcia D’souza, who was born and raised Goa, points out that, like anywhere else, Goa’s prices are driven by demand. And it doesn’t explain the recent outrage on social media because it’s not a new thing either. “The price rise started post 2020, when a lot of city folks moved to Goa to work from here. Rentals, hotels, coffee shops—everything got more expensive, but prices have pretty much stayed the same since,” she says.

Treasury, on the other hand, hopes the higher prices—and the furore over them—serve as a filter against poorly behaved tourists. “Rowdy tourists are not welcome in Goa. If Goa has to be a little more pricey to prevent that, I am okay with it. I have spoken to so many people here and they too said they are willing to pay more if it means Goa remains peaceful,” she tells us.

The Goa government has, for a few years, been saying it wants to reposition itself as a luxury travel destination to pull in more affluent foreign visitors while discouraging the more budget-conscious domestic tourists. “But it’s very difficult to change an already existing model,” says Ashwin Tombat, co-founder of Adventure Breaks, an adventure sports operator in Goa. “They’ll get a lot of pushback from stakeholders who want things to remain the same. Also, in a country like India, how do you keep a destination high-end only? Everyone keeps talking about how Goa could be like Maldives which has only high-end, expensive establishments. But you can’t have the Maldives model in Goa—you can’t keep out the budget domestic tourists. It’s easy to knock the tourism department, but their job is not an easy one,” Tombat adds.

mid-day’s attempts to reach out to the Goa Tourism Department went unanswered till the time of going to press.

Meanwhile, rising costs seem to be turning away some major Indian spenders too. After 15 years of annual visits to Goa—sometimes even thrice a year—Prashant Shintre, a stock investor from Pune, considered buying a second home there a couple of years ago but was put off by the prohibitive property rates. “North Goa’s property rates are very expensive—Spanish villas there cost between R3 and 10 crore—and there’s no tranquility left in some overcrowded areas such as Calangute, Baga and Anjuna,” says Shintre, “South Goa is very peaceful, but land rates are still expensive. An investment of R1-1.25 crore is the bare minimum if you want an independent home.”

Not to mention, the property market there is riddled with red tape over land use permissions. Shintre points out another issue: “In Goa, the cash component of real estate deals amounts to nearly 50 percent, which makes it difficult to buy a piece of land—or one needs make lot of adjustments that are undesirable.”

Instead, he decided to look further north along the Konkan coast, known for its pristine beaches and the presence of plenty of mango, coconut, and betelnut trees. Plus, there was none of the noise and commercialisation that plagues pockets of Goa.

“Instead of paying upward of Rs 1.25 crore in Goa, I bought an independent plot measuring 3,700 sq ft near Guhagar, where I am building a 1,000-sq-ft house with lots of open space around. And, I still managed to keep the overall price tag well below R32 lakh. Moreover, it’s half the distance from Pune to my new home , compared to Goa,” chuckles Shintre.

Does this mean his yearly trips to Goa will stop? I won’t stop going completely, but will probably go less often now,” he says.

We ask Goan writer Shailendra Mehta what this means for the “Goan holiday dream”. Most people have had a “Goa trip” group chat at some point in their lives, especially during college years. Will the rising costs spell an end to that too?

“That’s unlikely,” says Mehta, “Ever since movies like Dil Chahta Hai popularised Goa, everyone has had this dream of going to Goa at least once. Those who have the money can go abroad, but for those who cannot do so, Goa is still the number one option. No other place has the glamour that Goa does.”

Take Navi Mumbai-based Faisal Tandel’s seven-year-old daughter Afsa Tandel for example. “Ever since she saw the music video for the [Tony Kakkar] song, Goa wale beach pe, she has wanted to holiday there. I am planning a trip for her now,” says the journalist.

What does he think of the barrage of posts online from people saying no one’s going to Goa anymore? “Goa kisko nahi jaana hain, yaar? At least in India, Goa will always be the place for anyone looking for a few days of sun, sand and fun.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!