As ASI reveals that an Uran infra firm is the heritage caves’ corporate ‘mitr’, we ask if the government scheme is just a chance to raise a hoarding at a prime spot, or an opportunity to resuscitate history and uplift lives of Gharapuri islanders

ASI has signed a five-year MOU with Mahesh Enterprises and Infra India for the development and maintenance of amenities at Elephanta Caves such as toilet blocks, landscaping, illumination, a souvenir kiosk and help desk. Pic/Getty Images

Should corporate entities with no expertise in heritage conservation be allowed to adopt monuments, or is this commercialisation of history? This is the debate raging among history and culture buffs in the state since it broke in late August that UNESCO World Heritage site Elephanta Caves has been adopted by a private company under the Archaeological Survey of India’s (ASI) Adopt a Heritage 2.0 scheme.

ADVERTISEMENT

Speaking to mid-day, the ASI has for the first time revealed the name of the “Monument Mitr”—Uran-based Mahesh Enterprises and Infra India. Anand Madhukar, ASI’s Additional Director General (administration), confirms, “ASI has signed a five-year memorandum of understanding [MOU] to develop and maintain amenities at Elephanta Caves such as toilet blocks, landscaping, illumination, souvenir kiosk, helpdesk. The aim is to enhance overall visitor experience.”

The ancient caves located on Gharapuri island in Uran taluka are famous for 5th-century basalt rock carvings of the forms of Shiva, as well as Buddhist stupas dating back to the 2nd century BCE. Elephanta Caves are the first monument in Maharashtra to be adopted under the 2023 scheme, which is a revamped version of the central government’s original Adopt a Heritage project from 2017. It allows companies to conserve and develop tourist-friendly facilities as part of corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives.

Naldurg Fort in Dharashiv (formerly known as Osmanabad) is held up as a success story of corporate partnership, with Solapur-based company Unity Multicons having invested Rs 11 crore into its upkeep over the past decade

Naldurg Fort in Dharashiv (formerly known as Osmanabad) is held up as a success story of corporate partnership, with Solapur-based company Unity Multicons having invested Rs 11 crore into its upkeep over the past decade

To Manoj Padte, Managing Director, Mahesh Enterprises and Infra India, the project is not just CSR. “I am a native of Gharapuri island,” he says. “I want to see the area flourish and we are happy to help ASI. If tourists get good facilities, they will visit repeatedly, and island residents will also benefit. We have already begun work on gardening and maintenance of toilets; installation of CCTV cameras, seating, and dustbins will begin post monsoon.”

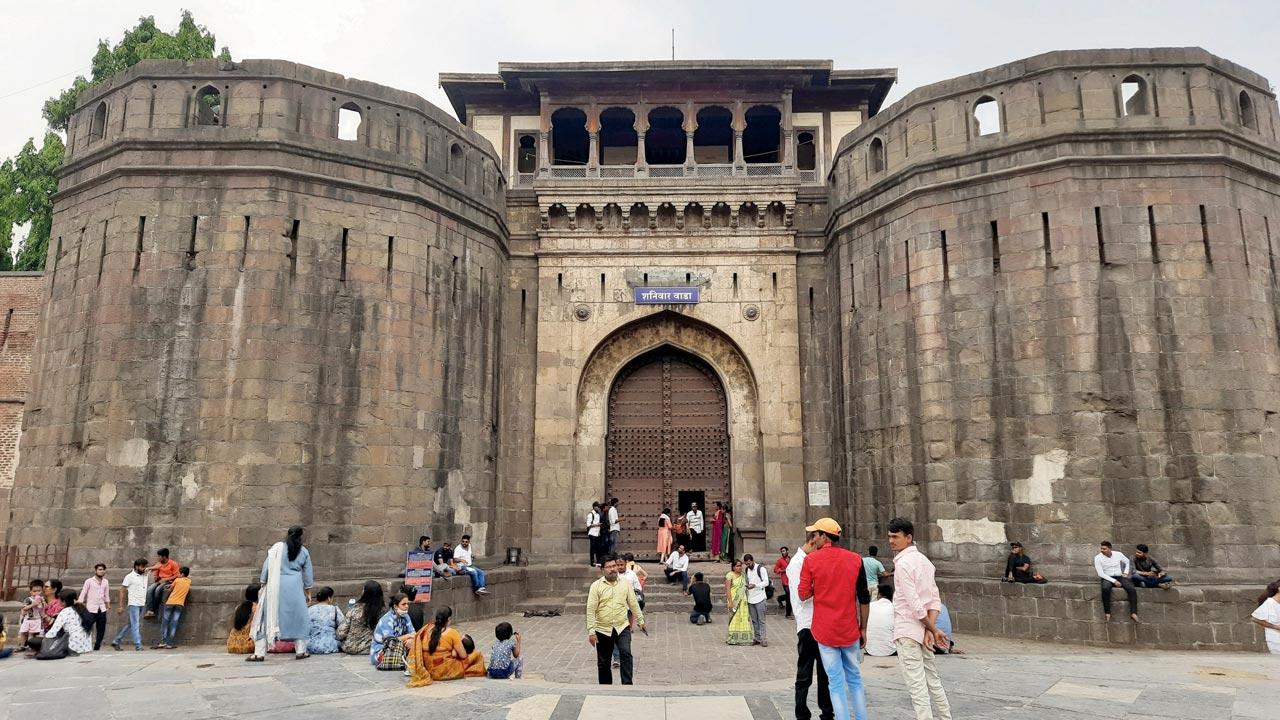

Also up for adoption are Pune’s Shaniwar Wada—built in 1732 as the seat of Maratha ruler Peshwa Baji Rao I—as well as the Aga Khan Palace, and the ancient Karla-Bhaja caves.

ASI’s move has come under sharp criticism. On the political front, Baramati MP Supriya Sule has lambasted the Centre for “selling national heritage”. Labelling the project “a bid to lease out national heritage sites to private companies under the guise of adoption”, Sule has called for its rollback.

Kurush F Dalal, archaeologist and culinary anthropologist, is all for the scheme. Having served on the panel advising a company on its pitch to adopt a historical monument, he reveals that there are very strict guidelines of what a company can and can’t do on site. “The ASI knows what it’s doing,” he says. “This is the only way to save our heritage without taking more money from the taxpayer. Once a corporate partner takes up development of peripheral amenities, instead of being overburdened by them, ASI can focus on the monument itself.”

But Anand Dave, President of Hindu Mahasangh, has threatened to move court if the government goes ahead with its plan. “This is an auction of monuments. These are all important historical landmarks—Shaniwar Wada is an icon of Maratha pride; Aga Khan Palace is where Mahatma Gandhi was imprisoned during the freedom struggle. These places are tied to our identity as Indians and Maharashtrians. What’s to stop these companies from commercialising our monuments like Udaipur’s Lake Palace [Mewar summer palace now run by the royal family as a hotel]? What’s to stop them from raising entry ticket prices so we can no longer afford a glimpse of our own history?” he says.

He also questions the expertise of the adopters to implement structural work in such close proximity to sensitive structures.

ASI’s ADG Madhukar, however, says there is no cause for concern: “ASI will maintain control of the main structure and all conservation work will be undertaken by our experts. The Monument Mitras will only work on developing and maintaining tourist amenities on the premises, such as toilets, drinking water, access roads, golf carts to ferry the elderly, CCTV cameras and lighting. Adopt a Heritage 2.0 is a win-win scheme. The resources of both ASI and the Monument Mitra would contribute to the development of the monument. More facilities will make the site more pleasant for tourists to visit. Rather than commercialisation, this will result in glorification of Maharashtrian history.”

Elephanta Caves is the first heritage site in Maharashtra to be taken up for ASI-corporate partnership under the central government’s Adopt a Heritage 2.0 scheme. It has been adopted by an Uran firm. Pic/Getty Images

Elephanta Caves is the first heritage site in Maharashtra to be taken up for ASI-corporate partnership under the central government’s Adopt a Heritage 2.0 scheme. It has been adopted by an Uran firm. Pic/Getty Images

But these activities are not without risks, cautions Nachiket Chanchani, Associate Professor of the Department of the History of Art and the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Michigan. “The risks of turning over some of our monuments to private firms and corporations are many,” says the cultural policy commentator and a vocal critic of the scheme. “To give just two examples: First, the construction of cafeterias and emporia on the grounds of protected monuments or even in their immediate vicinity may preclude archaeologists from excavating there [in the future] to unearth fragments that can nuance our comprehension of these historical sites. Second, lighting monuments at night and promoting night tourism might lead to excessive footfall, thus increasing wear and tear of these monuments.”

In 2016, when the northeast wing of Indore’s Rajwada palace collapsed, the authorities admitted that while that portion was in a dilapidated condition, vibrations from the light and sound show could have contributed to the mishap. The show was then briefly suspended and resumed after adjustments to the set-up.

In the 2.0 version of their scheme, ASI will oversee the script of light and sound shows, as well as ensure that cabling or electric poles do not disturb the view of the monument. “We will oversee where the projector is placed; the projection must not be on the monument directly,” says Madhukar.

Nachiket Chanchani

Nachiket Chanchani

However, Chanchani suggests, instead, that “it may be more prudent for interested parties to support ASI’s ongoing preservation efforts, and support universities and museums who are committed to training the next generation of archaeologists, art historians, curators, and conservators.”

Hindu Mahasangh’s Dave echoes: “If the government needs funds, why don’t these companies just contribute directly to ASI? The scheme is a massive branding exercise; they will be allowed to put up signboards outside, advertising that the monument is with them. Is this not commercialising our heritage? If I go to Shaniwar Wada, I want to see the fort, not a sign board proclaiming ‘so and so company’s Shaniwar Wada’.”

“Rest assured there won’t be a huge board saying ‘X-and-Y company Elephanta Caves’; that’s not going to happen,” Madhukar reassures. “We have prescribed the location, size and number of boards that can be placed such that visitors are not distracted.”

Controversy has erupted over the addition of Pune’s Shaniwar Wada, an icon of Maratha pride, to the list of monuments up for adoption

Controversy has erupted over the addition of Pune’s Shaniwar Wada, an icon of Maratha pride, to the list of monuments up for adoption

ASI will also ensure aesthetical harmony. “Say a monument is built of red sandstone, and a Mitra wants to construct a toilet. The block will have to be designed to match the aesthetics of the monument, and the design has to be approved by ASI beforehand. The Mitra can then place a sign outside it to inform visitors they have built it. The Monument Mitra won’t make profits, but they will get to proudly proclaim that they are contributing to the nation’s heritage.”

Goodwill alone from such an initiative can benefit companies immensely. In March, EaseMyTrip.com witnessed a 5.79 per cent boost in stocks after the announcement of its subsidiary arm, EaseMyTrip Foundation, adopting Delhi’s Qutub Minar along with three other monuments.

Dalal says criticism of the scheme stems from a lack of communication between the government and the public. “If the process is made transparent, a panel of respected heritage experts is formed, and the public is also allowed to make suggestions, it could receive fantastic feedback,” he says, adding this was the same criticism that hamstrung the first edition of the scheme in 2018 after public outrage over the announcement of the Dalmia group adopting the Red Fort.

In 2016, when the northeast wing of Indore’s Rajwada palace collapsed, vibrations from the light and sound show were suspected to have contributed to the damage

In 2016, when the northeast wing of Indore’s Rajwada palace collapsed, vibrations from the light and sound show were suspected to have contributed to the damage

The perks, he says, are many: “Imagine if the Jama Masjid in Mumbai is adopted. The corporate partner might provide valet parking—what a boon to visitors! That would attract many more. Most Indian monuments cannot be viewed at night because of missing illumination and lack of security guards. ASI would have to think twice before splurging on guards, but a corporate partner could easily provide security.”

The ASI has gone through its own learning curve after several attempts by cash-strapped governments to involve corporate investment in heritage conservation, including 2014’s Maharashtra Vaibhav State Protected Monument Conservation Scheme. Under this state government scheme, the hidden gem of Naldurg Fort in Dharashiv was adopted by Solapur construction company Unity Multicons. After initial missteps, such as the company erecting a Ferris wheel on premises—that was promptly removed by ASI’s intervention—the fort is now held up as a success story of what ASI-corporate partnership can achieve.

Dalal has been visiting Naldurg Fort for 20 years, and says the corporate helping hand has boosted tourism. “It has really been spruced up. Electric buggies have been introduced for the elderly, the ticketing counter was improved; the company developed and beautified the approach lane, and also built a parking lot. It’s no longer a desolate fort barely visited by people; I see more tourists there now.”

Anand Dave, Anand Madhukar, Kurush Dalal and Kafeel Moulavi

Anand Dave, Anand Madhukar, Kurush Dalal and Kafeel Moulavi

Kafeel Moulavi, Managing Director of Unity Multicons, tells mid-day that during its 10-year tenure, the company invested R11 crore in the monument’s upkeep as of CSR. “Naldurg Fort is a lesser-known but historically important site, with unique features. By adopting it, Unity Multicons aims to restore and bring attention to a piece of India’s medieval history, while also contributing to the development of local tourism.”

One of the major contributions by Unity Multicons was to assist ASI in removing encroachments. “Till date, 90 per cent of the fort area has been freed,” says Moulavi, adding that the company also made arrangements to remove vegetation growing on the walls of Naldurg Fort, preventing damage to the structure.

The company’s adoption tenure ended in July this year, but Moulavi says they are applying for an extension. “The scheme can be a success when carried out under strict government regulations guided by the goals of preservation, education, and public access,” he adds.

However, the project has revealed that ticket prices may need to be increased to support the corporates. So far, ASI has assured that ticketing, too, will remain with the government and the companies cannot change the prices. “The ticket rate is R10 per visitor,” says Moulavi. “Who can make a profit with this? The ASI has not increased ticket rates in spite of us requesting it. We’re applying for an extension in the hope of making up losses.”

Madhukar explains that under the current version of the scheme, “The Mitra can charge for certain semi-commercial amenities that develop and run, such as interpretation centres [museums], cafeterias and light and sound show, but prices will be regulated and the revenue will be poured back into upkeep of the monument. The entire project is not for profit.”

Closer home at Elephanta Caves, Mahesh Enterprises has its work cut out. The island, and therefore the monument’s upkeep, is crippled by accessibility issues. “Despite its historical and cultural significance, there has been little to no development on the island,” says Padte. “We grew up without electricity; it was only in 2018 that the island finally got 24x7 power supply.

Now, we hope to bring Internet connectivity here as well; there is no mobile tower on the island.”

He knows it’s an uphill battle: “Because it’s a heritage structure, many permissions have to be obtained. Add to that, developing any new facility is thrice as expensive here [on Gharapuri island] compared to the mainland, from where we have to bring bricks and rocks to construct even our homes.”

“But once we bring Internet connectivity, we can upload historical information about the monument for visitors to access at the caves,” Padte says, “This will improve their experience, as well as make life easier for islanders.”

10 L

No. of annual visitors at Elephanta Caves

0.72%

of CSR funds in India is budgeted for heritage conservation

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!