In light of today’s Delhi dharna for reservation, most Anglo-Indians say political representation will not help them, but as a community they insist they need it to speak for the scattered diaspora

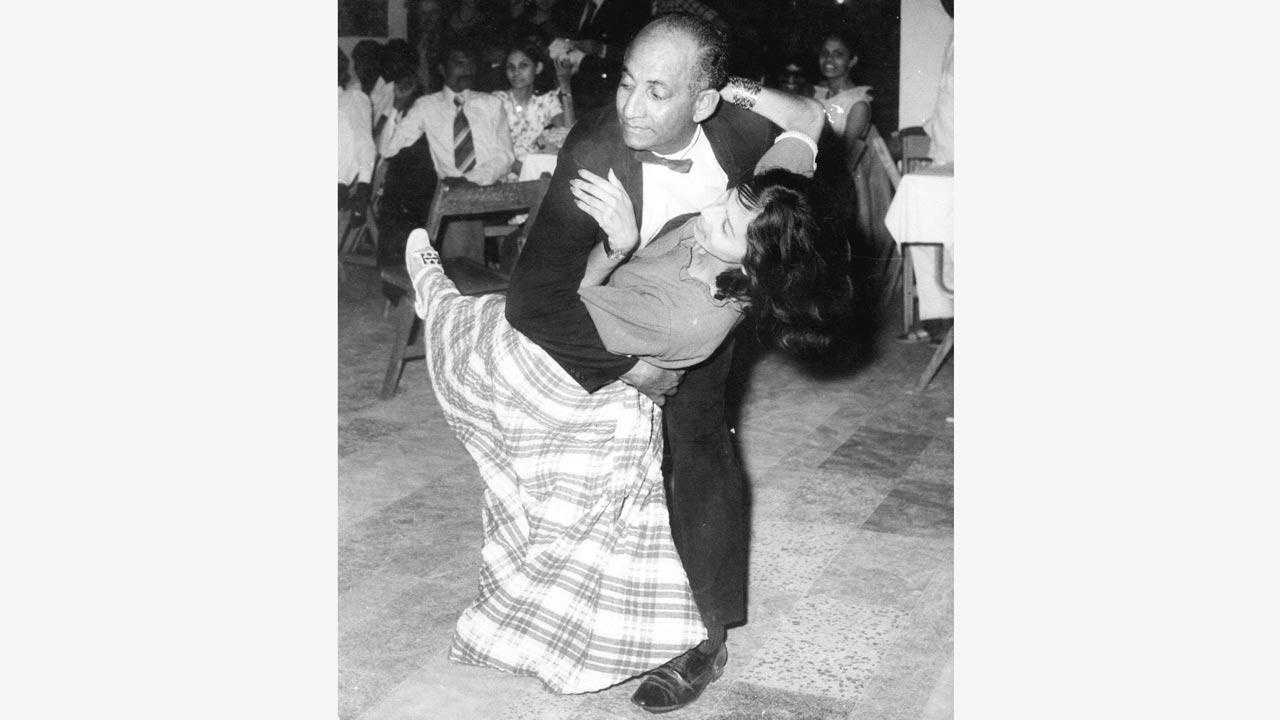

Clarice ‘Clarie’ M Griffin (in spectacles) and R. James ‘Jimmy’ Griffin (in the dark suit) at a dance in Vizag in the early 1960s. Their son, Peter Griffin, now lives in Navi Mumbai and is disconnected from the community

For a community that’s at least four lakh people-strong, the Anglo Indians are surprisingly invisible. Or have been rendered so. A large contingent, led by the Anglo-Indians’ Joint Action Group, has staged a dharna today at Jantar Mantar in Delhi for restoration of Article 334B that saved them two seats in Parliament, and one in each state legislative assembly. The 126th Constitutional Amendment came in 2019 on the foundation of the 2011 Census that counted just 296 Anglo-Indians in the entire country. A part of the error was that most of them were clubbed under the generic banner of Christians, and only a few classified as Anglo-Indians (AI). Summing up the members enlisted in various Anglo-Indian associations all over the country, community leader Gilbert Faria puts the population at four lakh.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nothing could underline the predicament of these “stateless people” more starkly.

Gilbert Faria with wife Sally Faria and former Anglo-Indian member of Lok Sabha, George Baker (centre)

Gilbert Faria with wife Sally Faria and former Anglo-Indian member of Lok Sabha, George Baker (centre)

“Through most of my childhood in Chembur,” says writer-editor Peter Griffin, “I was explaining who AIs are. In Bombay, many people think they have misheard and ask, ‘Mangalorean?’”

In the Constitution of India, Article 334 covers reservation for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in Parliament and Legislative Assemblies, and also the Anglo Indians. It was first stipulated for 40 years, and extended for every 10 years thereafter for each group, but AI was the first to be dropped. This has galvanized the community, but also laid bare a deep divide.

Train driver Noel ‘Bully’ Netto dances with his daughter Yvette at the Christmas Ball at Perambur Railway Institute, Madras in the early 70s. Up to the 1960s, jobs were reserved for the Anglo-indian community in the Indian Railways. Pic/Anglos in the wind

Train driver Noel ‘Bully’ Netto dances with his daughter Yvette at the Christmas Ball at Perambur Railway Institute, Madras in the early 70s. Up to the 1960s, jobs were reserved for the Anglo-indian community in the Indian Railways. Pic/Anglos in the wind

Some insist that the thinly spread community needs representation in Parliament to protect their unique culture, but there are those who feel that the community neither needs it, nor will benefit from it.

“In 2020,” says Faria, president of the Delhi-based Anglo Indian Welfare Association, and vice president of the Federation of Anglo-Indian Associations (FAIAI), “they brought out a bill that on the grounds that there are just 296 AIs in India [as per the 2011 Census), and that they are well off and don’t need representation. That was baseless and incorrect. We are asking for restoration of this article which provides representation.”

Demonstrations at Jantar Mantar, in Delhi in March 2020

Demonstrations at Jantar Mantar, in Delhi in March 2020

They did this arbitrarily, without consulting the community,” says author and educationist Barry O’Brien, whose book The Anglo-Indians: The Portrait of a Community, had a soft release online recently. “If the Government claims that there are only 296 AIs, then why did it nominate two representatives in the Lok Sabha in 2014?” O’Brien is also president-in-chief of The All-India Anglo-Indian Association, which has 63 branches across the country.

Educationist and political leader Frank Anthony was instrumental in AI being covered by the Article, arguing that since they did not have a state, their interests would be overlooked. Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru agreed to make special provisions and two seats were reserved for them in the Lok Sabha. Anthony was a lawyer and chairman of the Inter-State Board of Anglo-Indian Education and founder of the All India Anglo-Indian Educational Trust that administers six schools in New Delhi, Bengaluru, and Kolkata. He was also the chairman of the ICSE Council.

Ernest Flanagan, Barry O’Brien, Barry Rodgers and Peter Griffin

Ernest Flanagan, Barry O’Brien, Barry Rodgers and Peter Griffin

Up until the 1960s, the community had job reservation in the Indian Railways. Thus, large numbers from the communities collected in various Railway quarters, and could get a job after passing Class 9 (as per the Matriculation system) “I grew up in Trichy,” says Harry Maclure, who runs the diaspora magazine Anglos in the Wind from Chennai. “My father was an engine driver. We got a good education in the Railways school, they provided uniform and school books. We were treated in Railway hospitals for free. In return, we gave our blood, sweat and tears to the country.”

Griffin feels that political representation may not change much for the community as their push would be for the larger goals of the party that nominated them. “There have been MPs who have spoken in the Parliament for the continuation of the article but they have been part of different political parties,” says Faria. However, he stresses that such a thing is not always possible and hence getting Anglo-Indian representation is important for the community.

Darryl Dick and Harry Maclure

Darryl Dick and Harry Maclure

Journalist Barry Rodgers is cynical about any change. “I don’t think political representation has ever helped,” he says. “Even when our interests were safeguarded by the Constitution and representation, the leaders didn’t go above and beyond to do anything in metro cities, leave alone smaller towns and railway colonies. There is very little to encourage studies; the scholarships are of very meagre amount. There is little done for even those who excel on the field. There is no funding for their dreams, nor do elected officials open doors to opportunities for them.” For instance, the academy set up by a tennis great could hold free camps or give particular attention to budding AI sportspersons. AIs have excelled in sports, particularly in hockey. At the 1928 Olympics, eight out of 11 players were AI; the team for Olympics 1932 had seven AIs, and in 1936, the number was six. “When my sister wanted to study law in Bangalore,” adds Rodgers, “the community scraped together a measly amount.”

“The average AI is not as underprivileged as someone from an oppressed caste is,” says Griffin, a Vashi resident. “There are schools run by AI [mostly founded by Anthony] where they are educated; they might not need job reservation also [as their education builds them up to easily being fit for employment]. We are not as good as the Parsis in taking care of our own. The diaspora is scattered thinly all over the country and the globe, mostly in Canada, Australia and England.” There were two waves of migration in the community —one around Independence and the other in the 1950s and ‘60s.

So, what does the community lack that reservation could fulfill? “We lack unity,” says musician Ernest Flanagan. “Not all of us are affluent; and those who are well-off, stay away. We need them to help the community. We are losing our identity faster than the Parsis. Anglos used to be all-white. Through intermarriage, you don’t meet blue-eyed, blondes anymore. You could pass an AI in the street and not know.”

“I know this may sound radical, but we don’t need reservation now. We might have at one point in time, but our youngsters are doing very well… they get into colleges, earn degrees, get good jobs,” says Maclure. “They should not depend on quota. We are Indians first, and AI later. We are a stateless people, but all of India is ours. We could drop a hat in Shillong or Trichy, and adapt and thrive with ease.”

However, this is the echo of the privileged. “We comprise 2.36 per cent of the total population, and poor people make up around 80 per cent of this,” says Darryl Dick, chief organiser of the Delhi-based Anglo-Indian Association. “Social welfare schemes need to be available. They require scholarships, job reservations and there is nobody to help them. The government promised toilets in all homes but we are looking for proper housing for our community.”

The number of these socio-economic members is unclear. “The All India Anglo Indian Association’s stance is that there may be some AI who are claiming to be backward, and that is their prerogative,” says O’Brien. “Most AIs do not see ourselves as a backward community. We are a forward community. Our schools are the most popular. We are in the Railways, hospitality [industry], and the Army. Because of the smallness of the community, and the fact that we are spread thin, we need a voice in the legislature.”

Faria has set on the task of collecting data of underprivileged AIs. “There are many people living below the poverty line,” he says. “Since the government also doesn’t have any data, we are going ahead and conducting a survey about who is living under the BPL, doesn’t have a BPL card, a ration card, etc. The exercise will be completed in two to three months.”

The sense of betrayal is strong. “In January 2017, the government called a meeting of AIs, chaired by then Union Minister of Minority Affairs Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi,” says O’Brien. “We were told this was an initiative by the Prime Minister and that they wanted to hear us out and come up with a plan. After that, we didn’t hear from the government. The next thing we know, the seats are gone. In spite of representatives of 17 parties supporting our cause, the government bulldozed its way through Parliament.”

Precisely the kind of thing a representative would have blocked until further discussion.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!