Created for galleries or cities, installations are known for both, their grandiose size, and the specific identity they occupy. What then happens when the show is over?

Valay Shende's giant sculptures and installations, when not on display, sit in an 8,000 sq ft warehouse in Andheri East or are packed up in crates. Pic/Ashish Raje

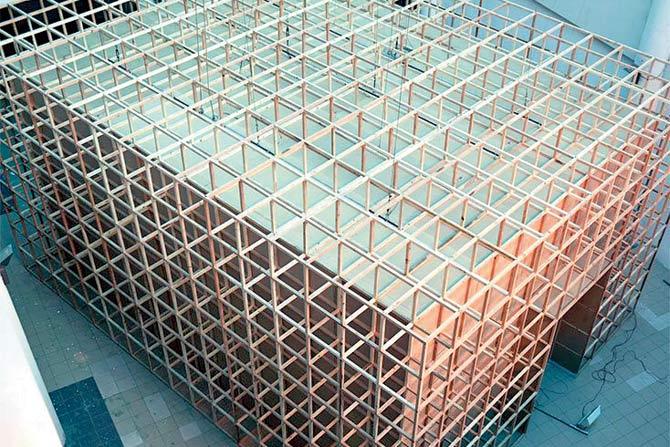

In 2013, Italian luxury fashion house, Zegna, through its worldwide art initiative—ZegnArt—invited 20 artists from India to propose a work for the Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum (BDL) in Byculla. The idea was to explore the possibilities of how a public space could be experienced. After multiple rounds, Mumbai-based Reena Kallat's proposal made the final cut. Her sculpture, when it was installed in 2013, was an oversized web formed by 400 rubber stamps that wove the history of the city on to the museum's front facade. Each stamp, made from fibre reinforced plastic (FRP) bore the colonial name of a Mumbai street that had been replaced by an indigenous one. The work involved the construction of a scaffolding and 45 people to hoist it on to the facade of the main museum building, a 45x55 feet structure. The process that also involved structural engineers who helped identify load-bearing points on the 148-year-old building, took close to 10 days. It took half a week for the entire piece to be brought down.'

Kallat's sculpture, Untitled (Cobweb/Crossings), is now a part of the museum's collection and, as per its agreement with ZegnArt, the museum is to display it from time to time throughout the decade. One of the times the sculpture was exhibited, only a part of it was used since the piece was on display inside the building. When it isn't on display, the piece is packed into storage in BDL's godowns.

ADVERTISEMENT

Valay Shende's Transit is a life-sized truck made of thousands of shiny metal discs and some 170 dismantlable parts. It has travelled to locations across the world and now sits at Lower Parel's Palladium mall. Pics/Bipin Kokate

Valay Shende's Transit is a life-sized truck made of thousands of shiny metal discs and some 170 dismantlable parts. It has travelled to locations across the world and now sits at Lower Parel's Palladium mall. Pics/Bipin Kokate

Unlike paintings and photographs, displaying site-specific installations and sculptures, requires logistical support and labour. Depending on the size and nature of these installations, it could take a few days to a couple of weeks to, first, install and then take it down. Equally subjective is what happens to these creations after they are dismantled. Commissioned works go back to the person or institution, as in the case of Cobweb/Crossings. If the artist has invested their personal funds, the installation returns home with them. How it lives on, depends as much on the artist as it does on the work.

In the case of Valay Shende's much-instagrammed sculpture Transit, a life-sized truck made of thousands of shiny metal discs and some 170 dismantlable parts, it travels to different locations. Shende—who is known for the use of stainless steel discs—conceived Transit in 2010 as a commentary on labour and migration. The truck's rear-view mirrors display video footage of roads in Mumbai. Seen from the driver's perspective, it gives the impression that the vehicle is moving while, in reality, it is stationary, suggesting that development is illusory.

In 2018, when Rashid Rana saw his installation that had taken Eve Lemesle two weeks to put together at the Dhaka Art Summit, he asked for its angle to be changed

Since it isn't a site-specific piece, Transit has travelled from galleries and corporate parks to shopping malls. It made its debut at Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon where it was the showstopper of the 2011 edition of the Indian Highway group show. The show was conceived in 2008 by curators from London's Serpentine Gallery and Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, to showcase the works of a new generation of Indian artists.

As part of the show, it also travelled to Rome's MAXXI (Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo or National Museum of 21st-century Arts) in 2011 and then to other countries. "I received the piece back after two-and-a-half years," Shende says. "After a display at BDL for about six months, in 2013, Peninsula Corporate Park wanted to do a show and requested for Transit to be loaned to them."

Of the 60 towers that Martand Khosla created, only 25 are on display at Gallery Nature Morte in Delhi, and gallerist Peter Nagy says that a client is likely to buy a maximum of five. Khosla has agreed to ‘break’ the installation

When not on show, Transit is on display at Shende's studio, a sprawling 8,000 sq ft space in Andheri East or packed up in crates. Each time this has to be done, it requires at least 25 staffers and a week to 10 days to ensure all parts are accounted for and packed correctly. At the moment, it occupies a prominent spot at Lower Parel's Palladium mall, thumbing its nose at the luxury shopping destination that was once a mill.

Unlike Shende's sculpture, Shilpa Gupta's 2013 installation hasn't, strictly speaking, travelled out of Bandra. The installation, which went up on the Carter Road promenade in February that year, involved lights attached to a set of acrylic pipes. As the sun set behind it, the lights would reveal the words, "I live under your sky too" in Urdu, Hindi and English, in turn. The installation was made specifically for the site and involved Gupta, who creates interactive installations and works with multiple media including video, photographs and lights, visiting the location multiple times.

Martand Khosla

Martand Khosla

"To get a sense of the scale, I printed [a mock-up of the installation] on a flex sheet in different sizes, walked back and forth to see how it looked in terms of scale and how it would look from different angles. I also had to source LEDs that would stand the humidity and would be of appropriate size and colour," Gupta, 43, says. Since everything about the installation was customised for Carter Road, the piece couldn't have been displayed anywhere else. At the moment, it lies at her Mumbai studio, packed up.

The American art critic and journalist Zoë Lescaze writes in the New York Times Style Magazine, that though the idea of site-specific installations emerged in the '60s and '70s in defiance of the notion of art as being something that could be moved or sold or put on walls, over time 'the orthodox sense of site-specificity has given way to reform interpretations that allow works inspired by one setting to be relocated and modified to suit others.

Reena Kallat's Cobweb/Crossings sculpture of 400 stamps took 45 people including structural engineers to haul it up on the facade of Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum

So it is with Gupta's installation, too. A version of it—with the text in Swedish, Sami and Arabic—was shown in Stockholm. Come 2020, it will be permanently installed in the neighbourhood of Rinkeby.

Some of her other installations live on in much more unique ways. Markings, that was shown at Tarrawarra Museum of Art in Australia earlier this year was made on site using concrete. The installation had the words, 'The markings we have made on this land have increased the distance so much' engraved and the slab was then broken up. Visitors were invited to take away the pieces. "Today, that installation is scattered all over the world in the homes of people who took a part with them," Gupta says.

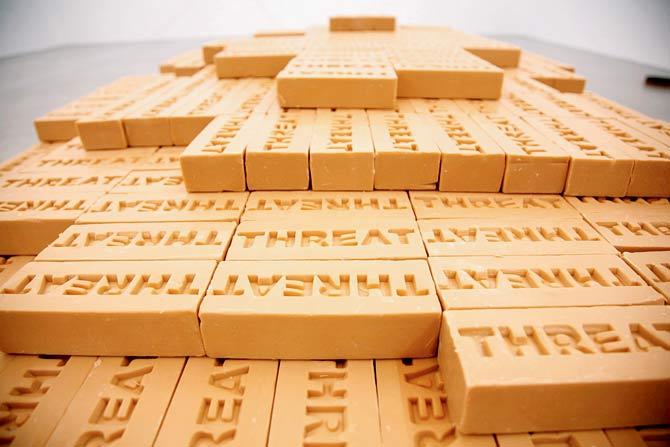

It's also how her 2008-09 Threat, lives on. The original piece was made up of 4,500 bars of soap the size of bricks. It has travelled to a dozen locations; each time the size of the block reducing as visitors take away a brick. "There are only a few bars left with me. Others survive in various parts of the world, I don't even know where."

Reena Kallat

Depending on whom you ask, artists are or aren't amenable to tailoring their work to a collector's specifications. Shende and Gupta aren't. In such cases, the works simply wait in crates or stay on display at artist studios till a gallerist or a buyer comes along.

Peter Nagy, artist and founder of Gallery Nature Morte, Delhi, says an artist may be open to altering their work to the bespoke needs of the buyer depending on where s/he is in their career. "Younger artists tend to be flexible; older artists sell to museums and when that happens, they aren't flexible," he says.

Martand Khosla, an artist who Nagy represents, adapted one of his pieces for Nature Morte itself. For his second solo show at the gallery in 2019, 44-year-old Khosla juxtaposed luxury high-rises of urban India made from reclaimed wood and of varying sizes with pavement dwellers. "Of the 60 towers [that Khosla created], only 25 are on display," says Nagy, who is currently in talks with a client. But given the space, the collector will likely buy a maximum of five towers.

Eve Lemesle. Pic/ Fabien Charuau

While Khosla may have 'broken up' his installation, South African artist William Kentridge downsized his video installation so it could come to life again in a different part of the world. "When it was shown at the Tate Modern in 2008, I Am Not Me, The Horse Is Not Mine, used eight life-size screens. In India, we had to use much smaller screens because we didn't have that kind of space," says Eve Lemesle, who set up the installation at Volte in Mumbai in 2013.

Lemesle runs the Mumbai-based art management agency What About Art which offers, among other services, exhibition designing. "We work with foundations and produce exhibitions. We also have private clients for whom we install artworks in their homes and office," she says. "Because we have studios, we often help artists design and fabricate their installations, offer services of architects or structural engineers and a pool of relevant experts for each project. Setting up and dismantling installations is a part of our job."

Shilpa Gupta's 2008-09 installation, Threat, was made up of 4,500 bars of soap. At each location, visitors were encouraged to take away a brick

Think of Lemesle as tech support, for artists. Listening to her is like watching the BTS video of a blockbuster movie that reveals the madness and chaos that's part of the creative process. You'd imagine that installations that involve a lot building and construction are the toughest, but for Lemesle, it isn't very different than putting together a piece of IKEA furniture. The works tend to come with detailed instructions and photographs of the work taken from different angles. So, in 2018, when Pakistani artist Rashid Rana saw his installation—a huge wooden pavilion she'd taken two weeks to put together at the 2018 Dhaka Art Summit—and asked for its angle to be changed, she may have sighed but proceeded to disassemble and reassemble it without batting an eyelid.

Shilpa Gupta's light installation was customised for the Carter Road promenade

"It's the video installations that are tricky," Lemesle says, recollecting a piece she had assembled at the same edition of DAS as Rana's pavilion. "The artist was in Singapore, the tech person was in the US and I was in Bangladesh. There was a small tech issue that took the longest to sort because we didn't have the expertise in Bangladesh. After co-ordinating between the three time zones, I finally managed to put it together. The most complex installations are the new media-based installations that have elements of video, sound and are duration-bound." Significantly, these are also the easiest to store and transport.

Shilpa Gupta. Pic/ Shrutti Garg

Curator Saloni Doshi of Space 118, says that it could sometimes cost the galleries as much to move old media installations as it costs the artist to produce them. There is also the matter of getting such installation through customs that can be a separate headache. "You have to have someone from your team present to ensure that should customs ask you to open up one of the crates, it goes back inside properly and without breakage," says Shende, whose works involve a lot of metal. Compare that with new media installations. Once you put away the screens, speakers and other hardware, your installation exists only on a hard drive no bigger than the palm of your hand or on something a lot less physical—a data storage cloud.

Installation v/s sculptures

An installation tends to focus on arrangement use and the space around the artwork; a sculpture will focus on the subject it is portraying. This is the difference between Valay Shende's Transit, a life-size truck, and Shilpa Gupta's Threat, a block of 4,500 bars of brick-sized soaps that keeps reducing as people are invited to take away each bar.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!