There’s a difference between movies that try to explain India and those, like Shantaram, that exploit it. India is incidental in this TV series made by non-Indians for non-Indians

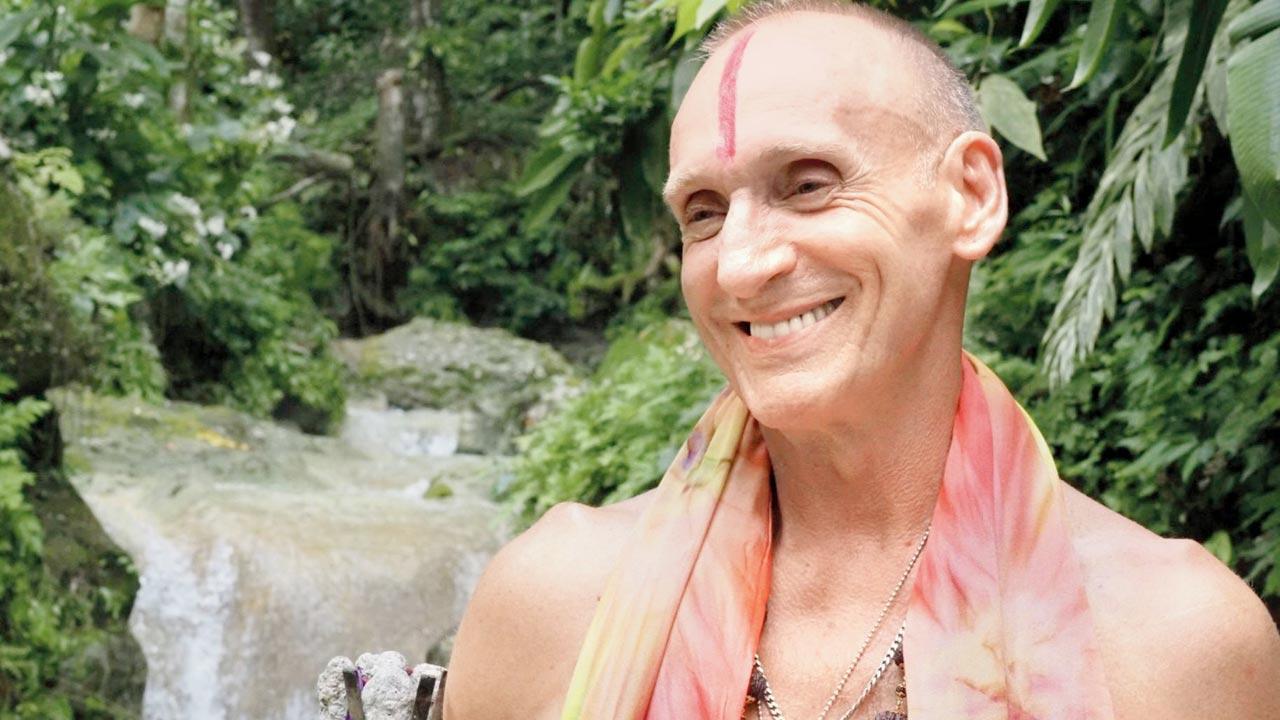

Realising that he had written the only best-seller he would ever write, G D Roberts did what every self-respecting hippie entrepreneur does—shaved himself bald, applied a red tika, put on saffron robes and wrote a book called The Spiritual Path

Call a bar. That’s what it sounded like. The person speaking was an underworld don of Mumbai and he was referring to one of his territories called, apparently, Call-a-bar. I had a moment of cognitive dissonance before realising that he was referring to Colaba.

Call a bar. That’s what it sounded like. The person speaking was an underworld don of Mumbai and he was referring to one of his territories called, apparently, Call-a-bar. I had a moment of cognitive dissonance before realising that he was referring to Colaba.

ADVERTISEMENT

On the TV in front of me was Apple TV+’s blockbuster TV series, Shantaram, based on the eponymous book by Gregory David Roberts that was quite the sensation in the early 2000s.

I haven’t read the book, I’m only a little embarrassed to say. Still, I know what the story was about. Lin, an Australian ex-addict prison escapee on the run comes to India to go underground, gets involved in crime, drugs, and starts living in a slum, where his minor paramedical skills make him legendary as a healer. Falsely accused of a crime he did not commit, Lin is a good guy in search of his essential goodness. As a review put it, Shantaram is a mix of “crime, humanity and redemption”.

That would make it box office material. They say Johnny Depp wanted to play the star role once. But it’s taken two decades for Shantaram to become a TV series.

Perhaps they should have waited a few decades more. Shantaram not only presses all my buttons but it is also one of the few eggs Apple TV+ has laid after a string of award-winners like Ted Lasso and Coda. I first watched it with some detachment, the way you watch a James Bond movie showing us what oriental, exotic India looks like.

Then I heard the crime boss Khaderbhai say ‘Call-a-bar’, and a switch flipped inside me. There are few things more cringe-worthy than a foreigner trying to speak like a local and flubbing it. But a $55-million movie in which they couldn’t be bothered to pronounce the name of the main location correctly?

Something is seriously wrong. And it has everything to do with the politics of trying to tell someone else’s story.

First question: how could an Indian director get an Indian name wrong? Bharat Nalluri sounds about as native as you can get. He’s not. He grew up in Newcastle, and attended the Royal Grammar School there. He’s thoroughly British.

All right, then. What about the underworld don, Khader Khan? Surely he would have known how to say Colaba? Ermm, no. Alexander Siddig, who plays the role, was born Siddig El Fadil in Sudan and is an English actor better known as Dr Julian Bashir in Star Trek.

Go through the cast list of Shantaram and you’ll see another oddity—not a single Indian from India stars in a major role. They are lookalike Indians either of British or Australian nationality who have lived away long enough to lose any lingering Indian sensibility or accent. Even Ravi, the slum boy who nurses anger against Lin for his mother’s death, is an Australian actor of Keralite origin, Matthew Joseph.

It’s possible they were trying to circumvent the politics and bureaucracy of Bollywood unions. Or perhaps they didn’t think Indian-born Indians could act as well as foreign-born ones.

The slums in Shantaram are sanitised and recreated in Thailand, the genuine ones in Mumbai being judged too grisly for western tastes. Real Indians and real India are merely the blurred backdrop for this TV series by non-Indians for a foreign audience.

Clearly, realistic accents and pronunciations couldn’t matter less in such a film. Behind it is the same profound indifference and insolence that makes an American call Iraq ‘Eye-Rack’ and say ‘Eye-Rain-Ian’ for Iranian.

There’s a difference between movies that try to explain India and those, like Slumdog Millionaire and Shantaram, that exploit it. Being a clever writer, Gregory David Roberts understood that he wasn’t writing for Indians but for a white, western audience who liked their oriental spirituality and mysticism shaken and stirred with some crime, sex, violence and hard knocks. If life kicks you about a little, you can claim to have seen the divine light and people will believe you.

You couldn’t say it better than reviewer Sandipan Deb did: “write a book, make money, get stoned, babble about nirvana.”

Turns out that’s exactly what G D Roberts did. In 2015, he tried his hand at a 900-page Shantaram sequel called The Mountain Shadow. It landed with a squelch and was never heard of again.

Realising that he had written the only best-seller he would ever write, Roberts did what every self-respecting hippie entrepreneur does—shaved himself bald, applied a vivid red tika on his forehead, put on saffron robes and wrote a book called The Spiritual Path, with gems like “honesty is the river flowing into the sea of trust” and “success is the full expression of personal fulfilment”.

Perhaps one day Swami Gregory will deliver a free sermon at Mondegar Café. You know, the one at Call-a-bar.

You can reach C Y Gopinath at cygopi@gmail.com

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!