The tiny weaving clusters of Puttapaka, Choutuppal and Koyyalagudem are giving big daddy Pochampally a fitting fight in making their own place in the sun. Ahead of National Handloom Day, Sunday mid-day rides down NH65 to meet the breakaway ikat stars

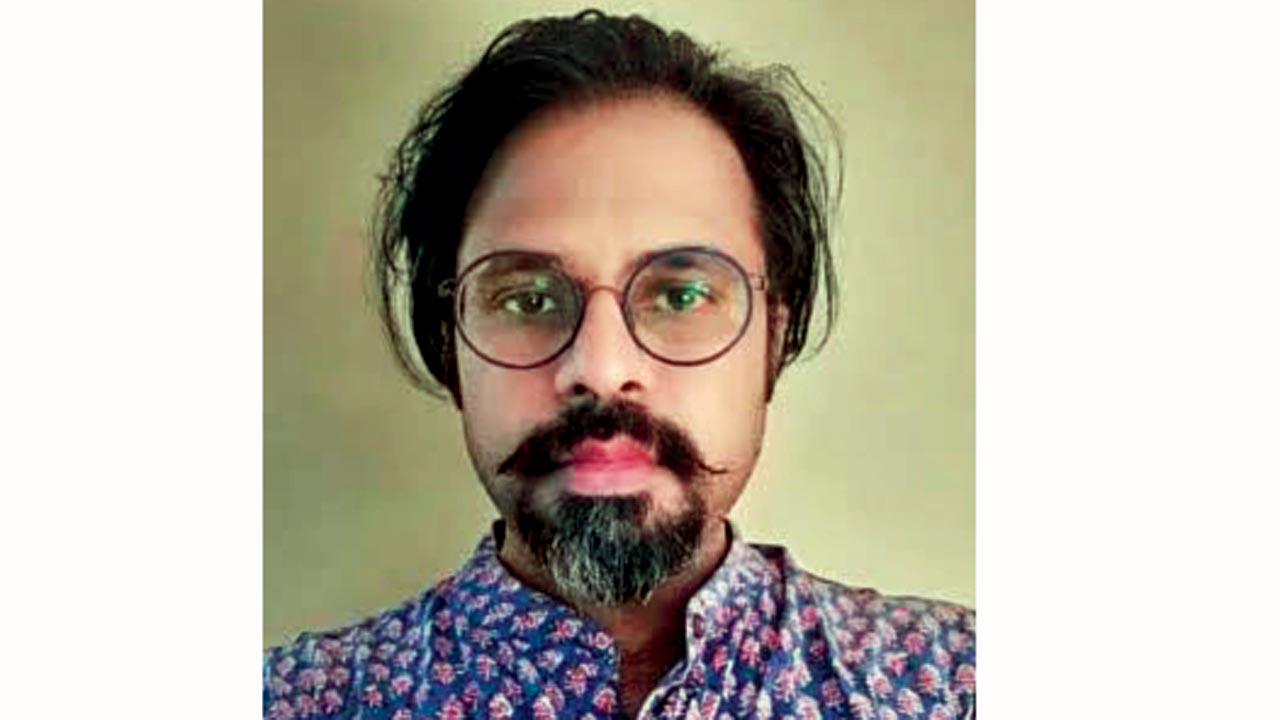

Karimikonda Venkatesham is a master double ikat weaver

Manish Saksena is a stickler for punctuality. Hyderabad and its surrounding province has seen unseasonal downpour the previous night. Saksena, 51, the lead at Aadyam Handwoven, hopes to hoodwink the physics of the monsoon by setting off early to Puttapaka village in Nalgonda district with a crew of journalists this June morning.

Manish Saksena is a stickler for punctuality. Hyderabad and its surrounding province has seen unseasonal downpour the previous night. Saksena, 51, the lead at Aadyam Handwoven, hopes to hoodwink the physics of the monsoon by setting off early to Puttapaka village in Nalgonda district with a crew of journalists this June morning.

ADVERTISEMENT

Cluster manager Ajith Kamarapu has shared the live location on Google Maps and will meet us there to take us to the weavers’ homes. Kamarapu, 35, has a diploma in textile technology and plays mediator between the corporate social enterprise that works with weaver communities in India and ikat artisans, also overseeing production and quality control. And on occasions, like on this visit, he doubles up as translator. “I was one of the first two hires when the brand launched,” he says proudly.

An Aditya Birla Group initiative, Aadyam formally launched with a store at New Delhi’s Khan Market in October 2020, followed by outposts in Mumbai, Hyderabad and Bengaluru; it also has a retail website. “The concept is built around creating a self-sustaining eco-system for Indian artisans by supporting and selling their crafts in the domestic and global markets, thus impacting their quality of life,” Saksena shares.

Puttapaka-based waft ikat artisan Gajam Venkateshwarlu’s father was an expert at the famed Telia Rumal, one of the most intricate double-ikat weaves; seen here inspecting street warping

Puttapaka-based waft ikat artisan Gajam Venkateshwarlu’s father was an expert at the famed Telia Rumal, one of the most intricate double-ikat weaves; seen here inspecting street warping

Currently, it works with communities in Bhuj, Banaras and Pochampally. Ikat textiles are revered in India and the West which made Pochampally an obvious choice. “There are ikat traditions in Orissa and Gujarat too, but those focus mainly on sarees. Pochampally ikat has a wider, multi-faceted use. Since our focus is split 50-50 between home textiles and apparel including sarees, shawls, stoles and pocket squares, it fitted the bill,” Saksena reasons, adding that his role is actually about “policing”. “I am like the [man at the] checkpoint; I ensure that what we produce with the design team followed by artisan partners preserves the essence of Pochampally ikat.”

While focusing on clusters in the famed Pochampally, it also works in the neighbouring villages of Puttapaka, Choutuppal and Koyyalagudem to create four collections annually; two for home textiles, and another two for apparel. “We are facilitators, but also co-creators and providers of infrastructure to the clusters. We ensure that their looms work 365 days a year to allow them a steady income. This is a partnership, not a transaction.”

We are on our way to Puttapaka and barely 60 kms down the NH65 highway, past Ramoji Film City, traces of Hyderabad, the state’s capital, have vanished.

Manish Saksena, lead at Aadyam Handwoven

Manish Saksena, lead at Aadyam Handwoven

The wide asphalt grid and humdrum of the highway shrinks to a pinched, dusty motorway lined by homes with cobbled roofs; the women in mildew-stained marigold and vermillion sarees gather to discuss the day around the rangoli decorating their porch. A shrine to the village pantheon arrives every two kms.

At Puttapaka, a small door opens to a spacious hall painted in the lightest of blues, the weathered wooden beams stand doodled in oil-colour floral designs. There’s a corner with stacks and rolls of undyed yarn or thread and ready fabric awaiting its destiny.

Waft ikat artisan Gajam Venkateshwarlu is with Padma, his partner in work and life, and they seem to have received a message from Saksena because Gajam gets right down to demonstrating how the yarn is bundled and bound in linear ties, meticulously by hand with thick rubber bands, a method used to resist the action of dye colours.

Yadagiri Rebba, 43, a weft ikat artisan has through training learned to work with pastel colours, a tougher task than working with bold, opaque shades which are relatively simpler to weave as the colours are easily distinguishable

Yadagiri Rebba, 43, a weft ikat artisan has through training learned to work with pastel colours, a tougher task than working with bold, opaque shades which are relatively simpler to weave as the colours are easily distinguishable

Next, Padma scoots behind the charkha and winds yarn on the bobbin, a cylinder spindle on which yarn is wound for the warp or vertical plane of the fabric. The couple belongs to Telangana’s traditional weaving community called Padmashali.

Gajam’s modest home, like that of other artisans Kundagatla Raju, Karimikonda Venkatesham, Prasad and Anumula Saidamma, has a compact kitchen while the largest expanse is constructed around the loom, dyeing unit and charkha setup. Modern inventions like a sewing machine and television are customary, as are framed photos of members of family and deities lining the quicklime-washed walls.

Gajam’s day begins at 7 am; he’s at work till 6 pm. Smaller weaving jobs take 15 days; the more complex ones take up to a month-and-a-half to finish, he says, pulling out printouts of preparatory design graphs shared by the brand. Dressed in a boardroom-approved checked white shirt, he grabs hold of the corner of his Madras check lungi to hasten his stride and gestures to us to follow him to an alley behind his home where “street warping” is underway. Outside weaver homes, yarn is removed from the warping wheel and tied between two poles to stretch and check the tangles. Thick rubber bands are inserted between the threads into the warp to make it easy to trace the entangled threads.

Ashwini, ikat artisan Kundagatla Raju’s wife, involves herself with pre-loom duties. Handloom work usually involves the entire family, so even if a woman doesn’t sit at the loom, she will be part of the allied workforce. The Fourth All India Handloom Census (2019-20) revealed that 72 per cent of India’s handloom weavers are female

Ashwini, ikat artisan Kundagatla Raju’s wife, involves herself with pre-loom duties. Handloom work usually involves the entire family, so even if a woman doesn’t sit at the loom, she will be part of the allied workforce. The Fourth All India Handloom Census (2019-20) revealed that 72 per cent of India’s handloom weavers are female

Circumstances, says Gajam, led him to quit school after class 5, but he had made sure that his children didn’t. His son has an MBA and his daughter is at college. He says of his wife, “I taught Padma to work with ikat but whether or not my kids wish to follow the family tradition is up to them. The 55-year-old has spent the last 40 years, including six at Aadyam, warping ikat. His father and guru was an expert in the coveted Telia Rumal, a double ikat weave. Financial conditions pushed the family to migrate to Navsari in Gujarat in the 1960s. They spent a decade there before returning to Puttapaka home built in 1986.

Half an hour away in Choutuppal, we are at the workshop of Yadagiri Rebba, 43, a weft ikat artisan. Rebba is his surname but because “Yadagiri is a common name, call me Rebba”, he urges. He works out of a one-room space, with his mother and wife, but it seems big enough to house a hand loom, floor desk and a nook for bubbling cauldrons of dyes. “It’s a given that the artisan’s wife has to help, otherwise it’s not considered a happy marriage,” Kamarapu chips in with a laugh, hopefully challenging the patriarchy in India’s handicraft industry where the hero work of weaving gets precedence over pre-and-post-loom work, which is critical and often performed by women.

A finished Pochampally weft silk ikat saree

A finished Pochampally weft silk ikat saree

Dressed in a bright pink ikat shirt over an orange veshti (dhoti), Rebba stands as a symbol of change. “[For the handwoven sector to survive], purana thinking and designs must end. My father owned a warping unit and I began working with weft ikat in 1996 straight after class 10. From then to now, not much has changed; no new innovations in how artisans approach patterns or colours. We must upgrade if we are to thrive,” Rebba says.

Saksena nods: “Artisans have an inherent sense of design; I don’t think you can learn that at fashion schools; they live and breathe it. What does not work in their favour is how the market pushes them in all directions leading either to simplifying the craft because it’s an easy and cheap sell, or replicating popular designs for the local market.”

It’s been three years since Rebba partnered with Aadyam. Since, he says, he has managed to polish his dyeing skills at their training sessions and learned to work with Indigo and AZO-free colours. “I used to work with bright acid colours. Now, I am an expert at mixing pastel shades. Though the first five months were difficult, I am now perfect,” he beams. Rebba’s experience is one Saksena has witnessed with most ikat artisans. Their preference for deep, dark, opaque colours had to be challenged. “It’s easier to weave a darker colour palette since you can easily distinguish the yarn while weaving. Design interventions like subtle woven patterns or softer pastel shades demand mature skills and also require a lot more effort from the artisan,” Saksena adds.

Though Pochampally is a name that is generally used for all ikat that comes from Telangana, artisans in the smaller surrounding mandals around big daddy Pochampally say in unison: “It’s all about the name.” Even as neighbouring weaving clusters like Choutuppal offer better designs, fighting the perception battle is tough. “It can get disheartening,” rues Rebba.

Gajam’s village is historically known for its double ikat—one of the most complicated to produce because here, warp and weft are resist-tied before weaving so that the pattern interlocks and emerges once woven on the loom. This process is the beating heart of the Telia weave. “But it continues to be marketed and sold under Pochampally ikats,” Gajam says with a shrug.

Telia Rumal, a unique tie-dye technique that uses oil to treat the yarn, emerged in the 19th century in Andhra’s coastal town of Chirala. From here it was exported to Africa and Arabia and worn as a keffiyeh (head scarfs). Its fame and fortune ensured it was widely adopted by Padmashalis who continued its practice in various parts of Telangana—while the craft became almost extinct in Chirala. In 2020, it secured a GI tag as Puttapaka Telia Rumal largely thanks to the efforts of master weaver, Padma Shri Gajam Govardhana, who in the late ’70s brought the craft back to his village, Puttapaka, some 240 kms from Chirala.

Pochampally ikat has turned into this collective term, like Banaras silk or Gadwal saree. “It’s the obvious development seen with most GI-appointed arts and crafts,” observes Saksena. “It is organic for craft to get displaced when weavers migrate to neighbouring villages as the land is cheaper. It’s also true of Banaras silks; today it’s mainly practiced in bordering areas like Ramnagar rather than in Banaras.”

‘Ikat is a knowledge stream, not just a skill’

Satish N Poludas recounts his experience of working with Pochampally ikat and why its making is more than just skilled labour

Satish Poludas

Satish Poludas

One of the first textiles that Satish Nagendra Poludas worked with after graduating from NID in Ahmedabad was the Pochampally ikat. After an introduction to hand-spun cotton however, his path veered away. “I got interested in desi cotton; growing it, developing technology for spinning and working with various clusters,” says the lead at Kora Design Collaborative. Headquartered in Hyderabad, the design and research practice is focused at the grassroot. “The emphasis is on domestic production and the local economy which enhances community spirit, relationships, and well-being,” Poludas explains. Presently, their work is focused in Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa, Bengal and Andhra Pradesh.

Poludas recently conducted a five-day introductory workshop on ikat for students of the School of Architecture at Christ University in Bengaluru. The idea, he says, was to get them to pay attention to the intricacies of one of India’s oldest crafts and respect the people keeping it alive. The students were taught how to build their own looms followed by a lesson on resist dyeing. Next, they’d visit weaving clusters in Koyyalagudem and Pochampally. “[I wanted them to] see the craft more as a knowledge stream than a skill,” he adds.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!