The India Art Fair was host to a delightful coincidence: an artist with a love for fabric, and a designer who works in fabric, with a nostalgic glimpse into art of visual storytelling

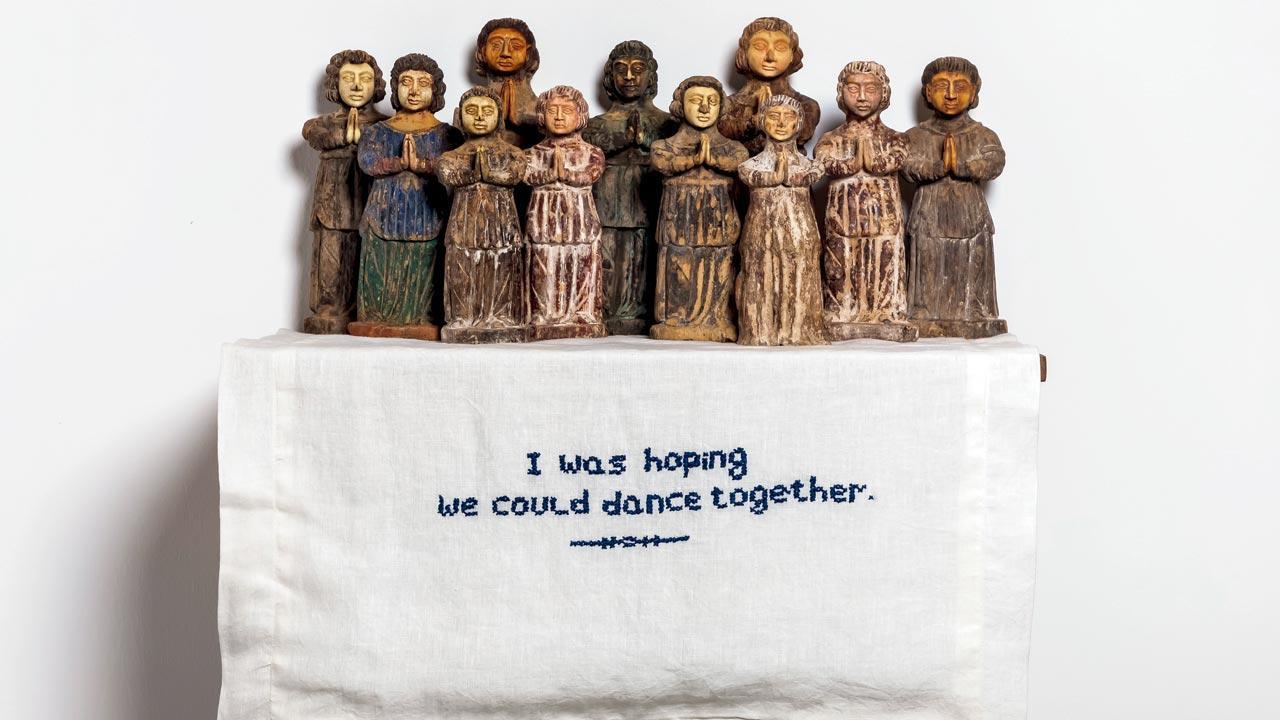

Inspired by the Alanis Morrisette lyrics, I was hoping we could dance together is a found-object art work by Saviojon Fernandes comprising 11 angels mounted on a cross-stitch scroll altarpiece framework. Pic Courtesy/Galleryske

Is he that fashion person?” Sunitha Kumar Emmart, founder of Galleryske, remembers being asked by a guest about Saviojon Fernandes at India Art Fair (IAF) in New Delhi.

Is he that fashion person?” Sunitha Kumar Emmart, founder of Galleryske, remembers being asked by a guest about Saviojon Fernandes at India Art Fair (IAF) in New Delhi.

ADVERTISEMENT

Indeed, Fernandes is that fashion aka resort wear designer from Goa represented by Galleryske since 2022. With addresses in Bengaluru and New Delhi, Emmart’s gallery is dedicated to presenting art grounded in contemporary Indian culture, featuring both emerging and established artists across diverse media, processes and approaches.. “Personally, I don’t see Savio as a fashion designer, because his clothes seldom follow trends. He is not making winter clothes while sitting in sunny Goa; they [clothes] are true to his home and everyday life,” Emmart reasons.

The two first met during the pandemic when Emmart visited Fernandes’s shop, 280 Siolim, with artist Sudarshan Shetty. “Sunitha and I hit it off instantly, and she encouraged me to be part of her group shows,” Fernandes tells us.

Saviojon Fernandes

Saviojon Fernandes

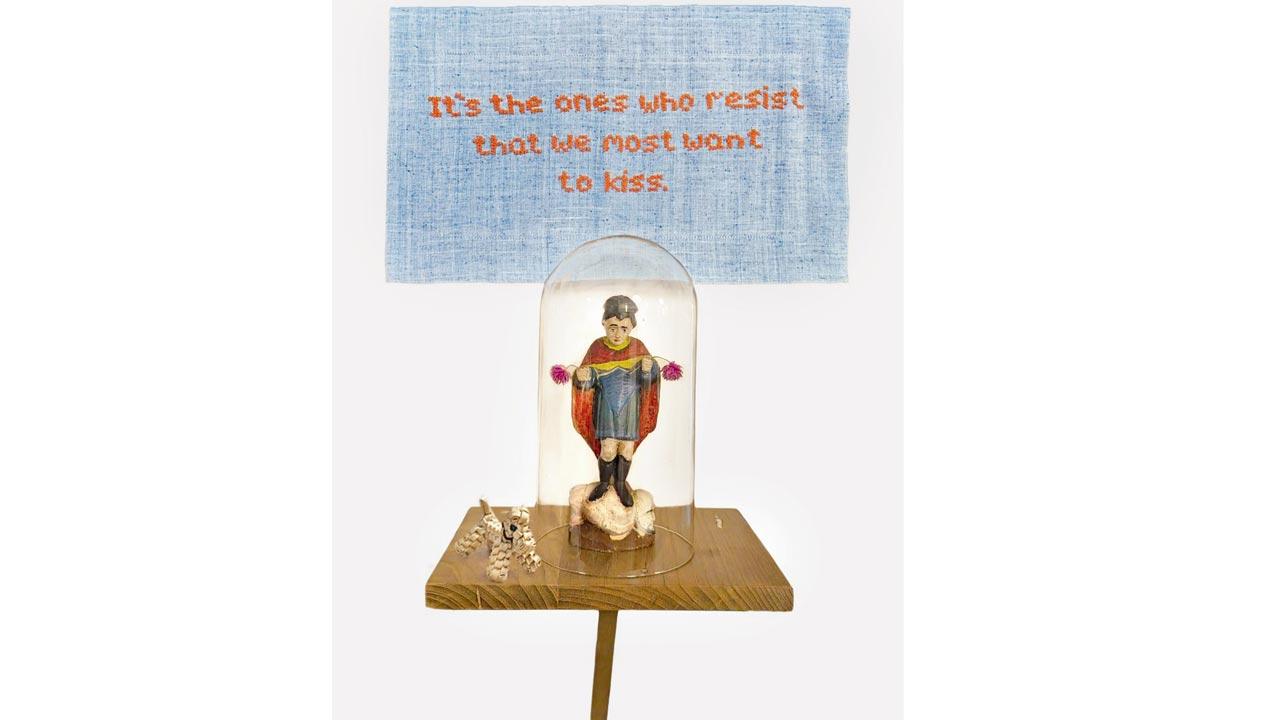

So began the designer’s tryst with art, resulting in two found-object art works displayed at IAF. Their titles are inspired by his favourite lyrics: I was hoping we could dance together by Alanis Morrisette, and It’s the ones who resist that we most want to kiss by George Michael. “Both pieces sold within two hours on the first day. I feel like I am moonlighting as an artist, which is amazing!”

Fernandes, who defines his work as “conceptual art, akin to a vintage teapot, ironic candle-stand or post-modern furniture”, for a while has been a found-object scavenger. You are sure to find him at flea markets in Goa, Mumbai, London and Europe. “Found objects like buttons, lace, cowrie necklaces, glass shards, artefacts are my chosen medium, and I am moved by the emotion of song lyrics when I create clothes or objects,” he says. Embroidered verses are a constant in his art. “But this time, we used cross-stitch on linen, commonly used as an altar frontal, and created altars from reclaimed teak wood to mount the objects on,” Fernandes says, adding, “There is something rock and roll about song-writing. There are many elements at play, from emotional context to how a line triggers off a memory… I am sure I was a groupie in my past life.”

It’s the Ones Who Resist That We Most Want to Kiss by Saviojon Fernandes features a figurine of Catholic Saint Roch, the patron saint of dogs, sick and invalids, and a dog raffia figurine he picked up from a Belgium flea market. Pic Courtesy/Galleryske

It’s the Ones Who Resist That We Most Want to Kiss by Saviojon Fernandes features a figurine of Catholic Saint Roch, the patron saint of dogs, sick and invalids, and a dog raffia figurine he picked up from a Belgium flea market. Pic Courtesy/Galleryske

It is interesting how reclaimed objects and materials take on a new and provocative character under the influence of his imagination. I was hoping we could dance together comprises a set of 11 angels with periscopic eyes; they seem to be looking in multiple directions all at once. “I noticed I was gravitating towards angel numbers 11:11; my birthday falls on March 22 and I have been seeing 11:11 a lot on my iPhone. It is also a play on the odd number 11 as a dancing pair, and a quirky fantasy of the angels wanting to dance,” he says.

It’s the ones who resist that we most want to kiss could be interpreted as a ritual object depicting Catholic Saint Roch, who is known as the patron saint of dogs, sick and invalids. But Fernandes would rather discuss its spiritual symbolism. He found this piece at a cousin’s home while the dog raffia figurine was bought from a flea market in Belgium.

Emmart says, “That Savio thinks he is new to the world of visual art works in his favour; he is not burdened by expectation. Whether you want to term his work high art or something else, the fact that his objects are able to start a conversation, excite and engage people across demographics, is important. Isn’t that what art is meant to do?”

Nilofer Suleman has long been curious about the human relationship with places and things. The Bengaluru-based artist started her career with cartography and miniature painting; she now maps makeshift myths set in the languorous and lush narratives and embroidered eroticism of textiles and jewellery, as vivid as Technicolor musicals. If you look closely, the details reflect sensory joys, like the satiric error we spot in a work titled, Mirza Saad Ali Unani Dawakhana: “Dawakhana is not opening on Friday”. She says: “English is not our first language, is it?”

In Mirza Saad Ali Unani Dawakhana, acrylic on canvas, Nilofer Suleman transports the viewers into fanciful versions of “roadside clinics” replete with campy characters, local textiles and satiric misspelling. (right) A close up from Unani Dawakhana reflects stories nestled within stories that her paintings are known for. Pic Courtesy/Art Musings

In Mirza Saad Ali Unani Dawakhana, acrylic on canvas, Nilofer Suleman transports the viewers into fanciful versions of “roadside clinics” replete with campy characters, local textiles and satiric misspelling. (right) A close up from Unani Dawakhana reflects stories nestled within stories that her paintings are known for. Pic Courtesy/Art Musings

Suleman spent her childhood in Indore and remembers being wide-eyed about its markets and gullies. “One crowded lane contained a tailor shop, a photo studio, a barber shop, all coexisting beautifully. Later, we moved to Mumbai, and lived across Maratha Mandir theatre with its ornate architecture and red chairs. Those are memories I can’t let go of. Mumbai’s Chor Bazaar is a pilgrimage for me; barring the COVID months, I have visited it every year,” Suleman says.

Showcased earlier this month at the India Art Fair (IAF) in New Delhi, Suleman’s acrylic on canvas works, including Mirza Saad Ali Unani Dawakhana, Miyan Shahnoor Family Studio, New East India Match Works and Bagh-e-Chinar, 1945, Purani Dilli are not definitive commentary on working-class reality, but a selection of experiences imagined to engage audiences in art without judgment.

Nilofer Suleman

Nilofer Suleman

Simultaneously campy, lyrical and ornamental, Suleman’s “exaggerated realities” could be described as visual notebooks, or even tiny anthropological investigations. What the paintings embody is the spirit of collage as they record small cultural moments of human ingenuity, nostalgia-stroking colour-saturated disruptions of movie posters, shop names, street graffiti, perfume bottles and studio portraiture.

Suleman professes her love for vernacular textile traditions, old brocades, Kashmiri embroidery on carpets and Palampore chintz; this also extends to Janamaz prayer mats. Working with textiles is instrumental in exploring cultural connections as well as personal associations. “Nilofer agonises over the smallest of details: how can I show the pleats on a kameez? Despite being an established artist, she approaches her work like a student and is always learning,” thinks Sangeeta Raghavan, director at Art Musings, the Mumbai gallery that represents Suleman.

Suleman was working on Unani Dawakhana when the Gaza war broke out. The devastating effect of the war fuelled her to address it culturally with symbolism—a small frame depicts The Promised Land and a Palestinian mother in a headdress bedecked with coins and ornaments holding a child in a green head turban, within the larger artwork. “Nilofer is a master storyteller,” Raghavan stresses. “In Unani Dawakhana, she fills up the canvas with kaleidoscopic imagery, nesting one episode inside another, arranging them within framed narratives and larger, circulating cycles of tales.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!