Six translators have teamed up to render an iconic Parliamentarian and socialist leader’s English books in his mother tongue

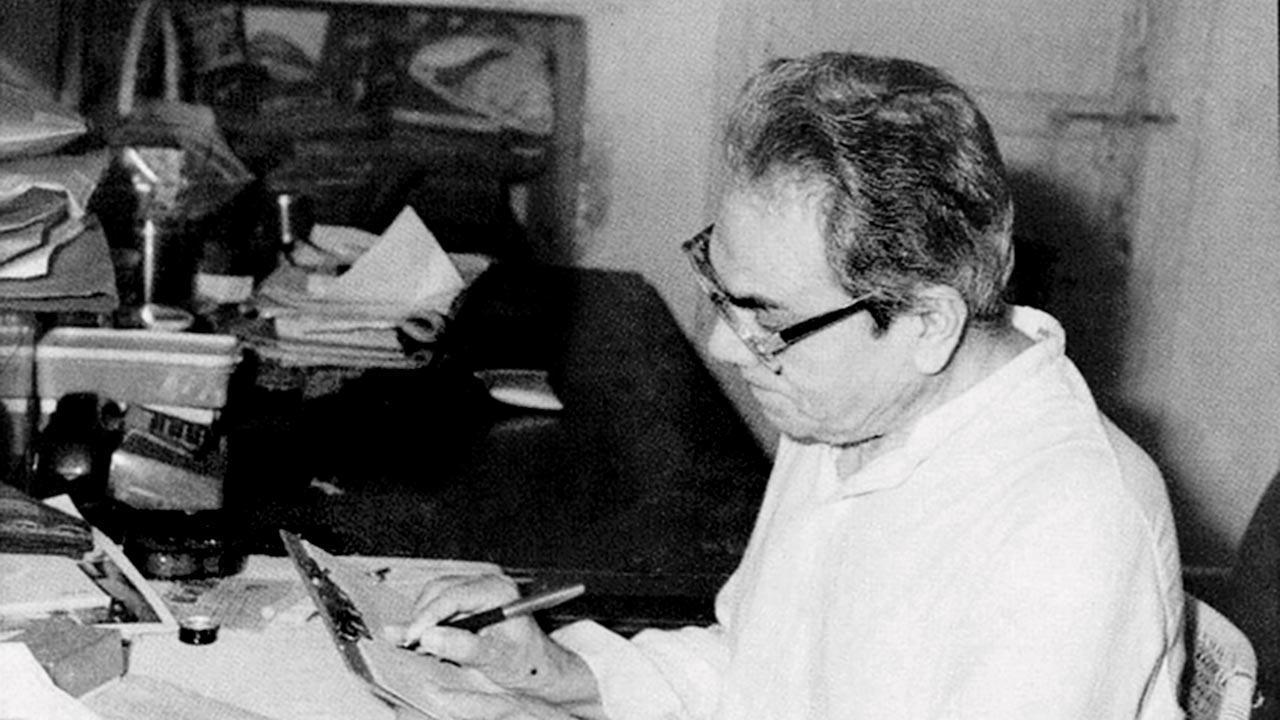

After withdrawing from active politics, socialist leader Madhu Limaye (1922-1995) penned over 25-odd English books. He cared for a wider national and international readership for his writings

February holds two important days—the International Mother Language Day, which is observed tomorrow, and the Marathi Language Day on February 27. Both are public reminders of the need to celebrate and preserve native expression. While one promotes multilingualism, the other honours the tenth most-spoken Indo-Aryan language, the government’s declared medium of communication in Maharashtra.

ADVERTISEMENT

Every year, this day is an interesting affirmation of the Marathi identity that is central to the state’s rulers-administrators across political divides. For the literati, it is an occasion to celebrate the power of the mother tongue.

For this columnist, the mother tongue connect was brought alive in an ongoing translation project. First, it was sheer good news that six translators-reviewers, of a certain vintage value, are racing against a deadline for the Marathi rendering of select English books of socialist leader Madhu Limaye (1922-1995). Second, the Marathi books are going to be serially published in the birth centenary year of the iconic scholar-leader, who is mostly recalled for his role in the Janata Party experiment of 1977. Third, the project is run under the aegis of two key institutions upholding socialist thought—Keshav Gore Smarak Trust and Sadhana Prakashan. Despite the mounting odds in the pandemic and the existential crises, these institutions have devoted energy for intellectual rigour.

His books are being translated as part of a project run under the aegis of two key institutions upholding socialist thought—Keshav Gore Smarak Trust and Sadhana Prakashan

His books are being translated as part of a project run under the aegis of two key institutions upholding socialist thought—Keshav Gore Smarak Trust and Sadhana Prakashan

Limaye wrote in English as a matter of choice. As his son Aniruddha Limaye, 67, who is part of the translation team, says: “Bhai’s [Madhu Limaye’s] love for languages—English, Hindi, Marathi and Sanskrit—was not laced with any chauvinistic pride. He belonged to that league of politicians who wanted to give a place of pride to Indian languages in post-Independent India. He was a follower of Ram Manohar Lohia, the socialist who articulated the ‘Angrezi Hatao’ slogan.” But their anti-English stance was not directed against the exposure to English books. Leaders like Limaye only wanted to reduce the influence of English in administration, judiciary and education, as that led to the disenfranchisement of underprivileged poor Indians.

Limaye cared for a wider national and international readership for his writings, particularly for his analytical arguments that were based on political, legal and constitutionally-sourced texts, usually written in English.

In a matter of 11-12 years (1983-1995), after he withdrew from active politics, he penned a variety of 25-odd English books such as Indian National Movement, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru: A Historic Partnership, Prime Movers: Role of the Individual in History, Problems of India’s Foreign Policy, Parliament, Judiciary, and Parties: An Electrocardiogram of Politics, and so on.

The five texts chosen for Marathi translation have a specific purpose—to reintroduce a forgotten socialist to his home state. Although born and raised mainly in Pune, Limaye, who did his early political work in Khandesh and Mumbai, is recalled as the intellectual from Delhi. He was also elected to the Lok Sabha from Bihar four times. During the 1957 General Election, because of the Socialist Party’s (the Lohia faction) stance to go it alone, he was branded as a “traitor” to the cause of the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement. When the Janata Government, led by Morarji Desai collapsed in mid-1979, Limaye was vilified as the party-wrecker because he raised the issue of dual membership/loyalty of the far-Right members of the party—pointing to the RSS. His books Birth of Non-Congressism and Janata Party Experiment in two volumes, are therefore worth visiting at this interesting juncture in Maharashtra, when an alliance of one far-Right and two Centrist outfits govern the state. Similarly, the other two books, Religious Bigotry: A Threat to the Ordered State and Contemporary Indian Politics, deal with the evolution of divisive politics using religion and caste as tools and shed historical light on several important challenges facing our nation.

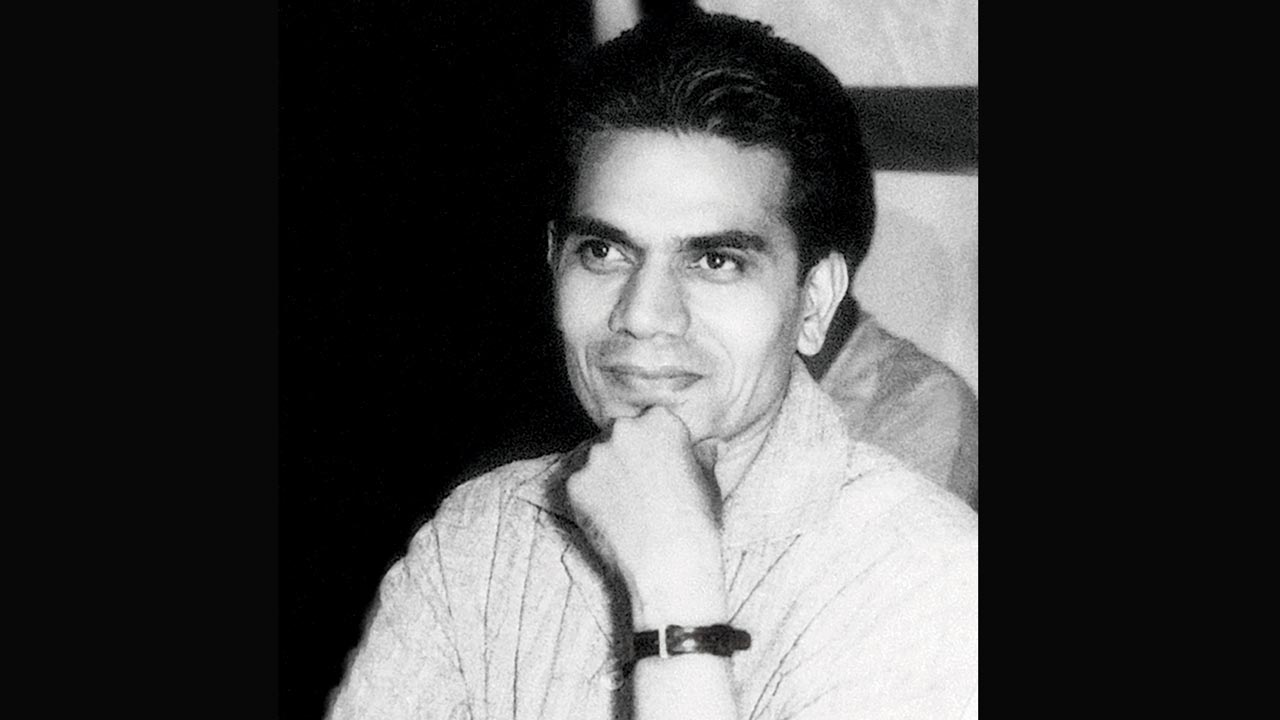

Born and raised in Pune, Limaye, did his early political work in Khandesh and Mumbai, before moving to Delhi. He was elected to the Lok Sabha from Bihar four times

Born and raised in Pune, Limaye, did his early political work in Khandesh and Mumbai, before moving to Delhi. He was elected to the Lok Sabha from Bihar four times

Art critic Amarendra Dhaneshwar, 70, who has played a key role in curating the translation showcase, feels that the books couldn’t have come at a more opportune time. Dhaneshwar prides on being Limaye’s mentee since the 1970s. Likewise, the other translators have their own Limaye lore. While Vasanti Phadke and Sunitee Jain were part of Bhai’s circle since his heydays in the Parliament, Vasanti Damle and Satish Kamat have a keen appreciation of Left-leaning socialist movement and literature. Phadke, 86, had in fact once offered to translate the key treatises. That was a while ago when her husband historian, Dr YD Phadke, broke bread with late Limaye over discussions on India’s political trajectory.

While the translators acknowledge the intellectual heaviness of Limaye’s volumes, they hasten to add their admiration for the author’s passionate interest in the parliamentary process and his painstaking documentation of momentous phases, especially the Emergency and thereafter. Jain, 75, says Limaye’s words are so carefully crafted that she has to “set aside every chore, especially cooking” to scout for the Marathi equivalents.

Damle, 76, shares a quirky aside about Limaye’s Hindi speeches. In 1968, when Damle was doing her MPhil course in Jawaharlal Nehru University, Limaye was hosted as one of the speakers on international affairs. “He used chaste Sanskritised Hindi words, which put off some of our students, who were expecting a more approachable Hindustani idiom.” The memory stayed with Damle for long; it prevented her from further meeting the parliamentarian in Delhi, when he was the cynosure of political action. Five decades later, as she translates Limaye’s anthology on religious bigotry and institutional decline in India, she regrets not having spoken to the visionary whose writings call a spade a spade. “His usages reflect his objective assessment of the non-Congress experiments, as well as the Left-liberal worldview.” Curiously, many Limaye fans—Damle not included—felt the leader’s Hindi oratory was imbued with “warmth” and “thehrav”.

During his Portuguese detention in Goa (1955-1957), Limaye wrote five letters to his little son, which were later published as an illustrated Marathi book titled Ladkya Poptas (For The Darling Parrot). The son is now busy reviewing the English rendering of his father’s autobiography Atmakatha. This is among the few texts which were orginially written in Marathi.

For Limaye, words were—whether in Hindi, English or Marathi—weapons in the political struggle, but they also came to his rescue, while he was in prison. He used to say that he can be happily jailed for the causes he espoused, if assured the company of books, particularly the Mahabharata and the Complete Works of Shakespeare. Among his regrets was the lack of time to learn a South Indian language and one European language, other than English. He never had the time or leisure for those endeavours.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar @mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!