Inside Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy exhibition, moments from Bengal’s past unfold, revealing new insights into the interwoven history of textiles, shaped by time, politics, and geography

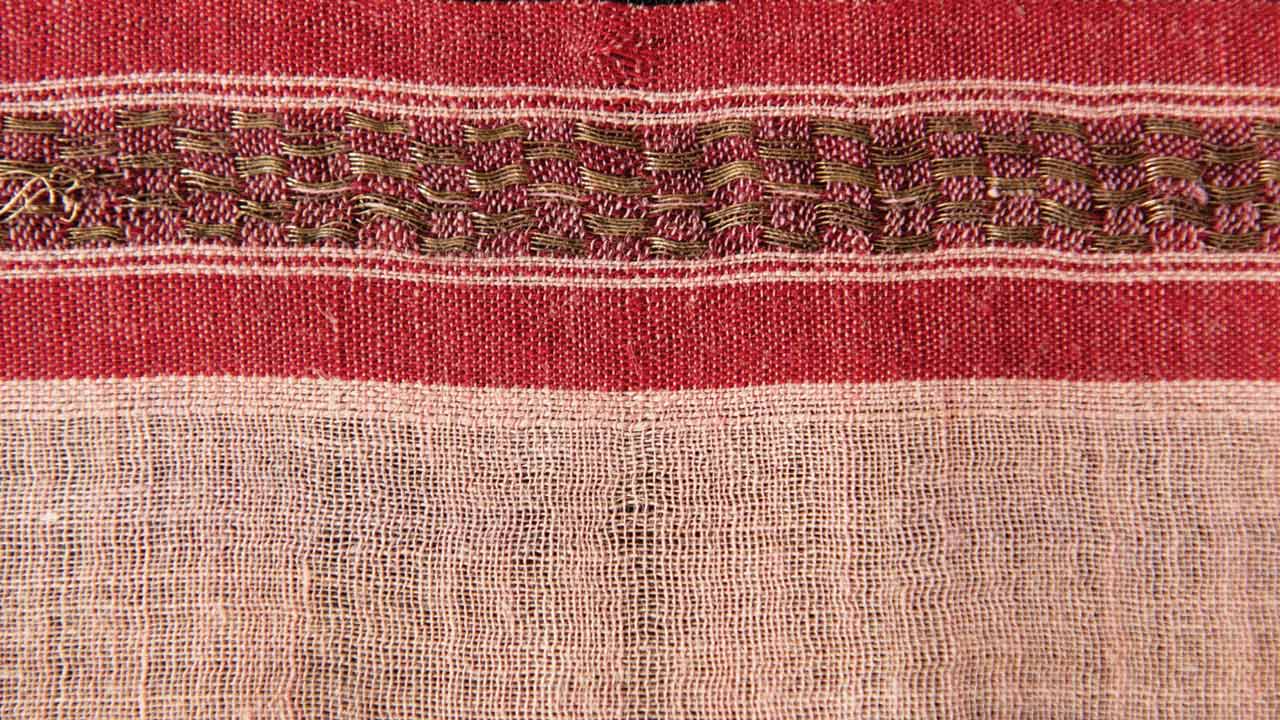

Muslin gown, woven and hand-embroidered fabric from Dhaka (Bangladesh), and tailored in France. Collection: Weavers Studio Resource Centre, Kolkata. PICS COURTESY/ SOUMYA PRASAD

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy, on view until March 31 at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity, offers an immersive journey through Bengal’s textile evolution, from the Mughal era to the 20th century. The exhibition evokes reverence for the past and wonder at what might have been, telling the layered story of two Bengals—West Bengal and Bangladesh—across four centuries. From Mughal patronage to catering to European market demands, Bengal’s textiles evolved through political, cultural, and trade shifts, marked by key moments like the migration of weavers post-Partition and political upheavals that reshaped the region’s cultural fabric.

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy, on view until March 31 at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity, offers an immersive journey through Bengal’s textile evolution, from the Mughal era to the 20th century. The exhibition evokes reverence for the past and wonder at what might have been, telling the layered story of two Bengals—West Bengal and Bangladesh—across four centuries. From Mughal patronage to catering to European market demands, Bengal’s textiles evolved through political, cultural, and trade shifts, marked by key moments like the migration of weavers post-Partition and political upheavals that reshaped the region’s cultural fabric.

ADVERTISEMENT

Presented by the Weavers Studio Resource Centre (WSRC), a Kolkata-based not-for-profit, and curated by Mayank Mansingh Kaul, the exhibition brings together 106 objects, including 81 textiles and 25 artefacts—clay models, a Mayurpankhi boat, and muslin swatches. Many pieces are rarely seen, with some making their public debut. It’s a deep dive across nine rooms, each with its own theme and colour palette, designed by Reha and Rajat Sodhi.

Darshan Shah and Mayank Mansingh Kaul

You’ll find muslins, kantha, jamdani, Indo-Portuguese embroideries, and Haji rumals (pilgrimage headdresses), along with a stunning Satgaon quilt reinterpreted by Mumbai-based Chanakya School of Craft. Royal garments from the Sheherwali Jain families of Murshidabad provide insight into Bengal’s diverse culture, while modern takes on jamdani by Bappaditya Biswas and Injiri push these crafts forward. Curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul explains: “This exhibition expands the narrative beyond the celebrated kantha and jamdani, highlighting Bengal’s artisans’ contributions to global textile culture.”

Darshan Shah, founder and project director of WSRC, adds, “The exhibition asks: What led to Bengal’s textile industry’s rise and fall? It also invites reflection on how its legacy still echoes today—and how we can revive Bengal’s textile traditions moving forward.”

Accompanying the exhibition is Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy (Mapin Publishing; R4,950), a comprehensive book edited by Dr Sonia Ashmore, Tirthankar Roy, and Niaz Zaman. Covering Bengal’s textiles from the 16th to 20th century, it explores trade, design, and production, along with insightful essays by textile historians and practitioners, and rare fabric photographs and historical maps tracing Bengal’s textile hubs.

Cultures nearly clash in a towering colcha (Spanish for quilt), recently acquired by the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, and loaned for the show. With its red madder-coloured ground and intricate floral embroidery, this rare, intact piece illustrates the intersection of Portuguese and local textile traditions.

Adding to the cross-cultural conversation is a muslin gown, woven in Dhaka (Bangladesh) and tailored in France. Shah recalls finding it online for £400 (roughly Rs 40,000). “These days, you can’t even buy a saree for that amount,” she says.

But purchasing and shipping the item to India proved challenging due to the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA), which made it difficult for Shah’s non-profit to proceed despite ATG certification. Shah contacted Dr Ashmore in London for assistance, who helped secure and transport it to India, where it arrived in its original cardboard box.

The last time Shah encountered Bengal’s textiles was in 1979, at the Arts of Bengal exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London. “But even there, textiles were a mere fragment of the story, overshadowed by other arts. Later, at the Fabric of India exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum (2015-2016), I was struck by how little representation Bengal had—despite once being renowned for clothing the world. I wondered: what happened?”

Shah’s quest to uncover answers took her on a journey through Bengal’s nuanced and expansive history. She believes, “Only by understanding Bengal’s textile legacy through research, oral histories, and the shifting political, cultural, and trade landscapes can we begin to grasp its present and future.”

OUT OF THE PAST: FIVE LEGACY TEXTILES

Begumbahar: Bengal’s whisper of luxury

Whisper-thin and translucent, the Begumbahar saree became a symbol of luxury in Bengal’s high society. Described in Tant O Rang by Trailokyanath Basu, it was said to be a checked cotton-silk saree from Tangail, though no veteran weavers from Tangail or Santipur recall the name, suggesting it was a marketing term used by Calcutta shops in the 1940s-50s.

Begumbahar, woven cotton and silk, Bangladesh, 1960s. Collection: Ruby Palchoudhuri

Craft expert Ruby Palchoudhuri’s mother-in-law, Ila Palchoudhuri, bought stacks of these delicate sarees for ₹250 each from Rashid’s mother (a colloquial term for women in Bengal), who imported pastel-hued sarees with subtle zari from Jessore (now Bangladesh) and sold them to Calcutta families. Unlike coarser Dhonekhali and Santipur sarees, Begumbahar sarees were prized for their soft, fluid texture and understated luxury, and remained highly coveted.

On summer evenings, women from North Calcutta’s elite families painted their backs with alta, draped in these sarees, and danced at terrace parties. Saree historian Rta Kapur Chishti describes how the fabric’s on-loom sizing gave the Begumbahar a rustling quality, adding to the atmosphere.

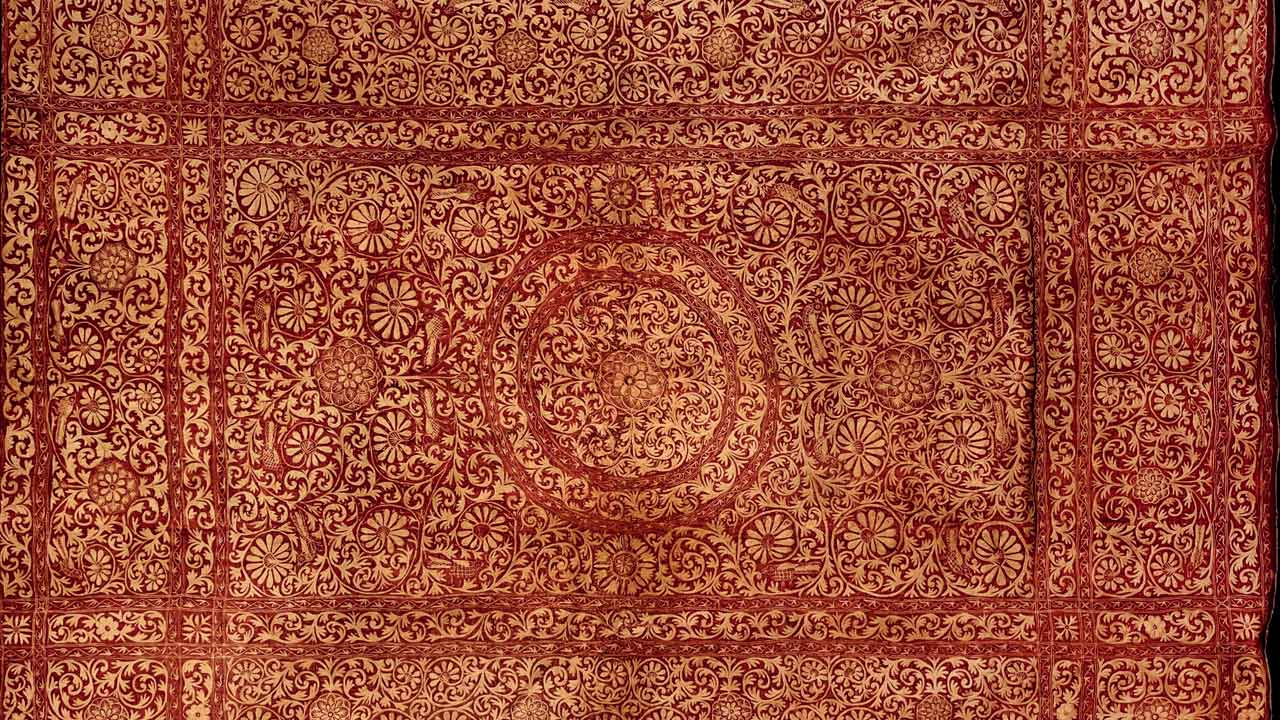

Colcha: Bengal craft meets European markets

The colcha, a golden-yellow embroidered textile, is one of the earliest surviving examples of Bengal embroidery, prized for its craftsmanship and hybrid designs. In the 16th and 17th centuries, these textiles were exported to Europe, where they became highly sought after. Crafted by Bengal artisans, colchas featured European-inspired iconography—war scenes, pelicans, and medallions—reflecting both local and foreign artistic influences.

Wall hanging or spread (colcha), cotton and silk, plain weave with hand embroidery, made in Satgaon or Hughli, Bengal, for the Portuguese or Iberian market, late 17th - early 18th century. Collection: Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

Valued for their craftsmanship and role in the global textile trade, they remain one of the few material traces of Portuguese activity in Bengal. Did they influence Indian textile production for export to Europe and pave the way for later European interventions?

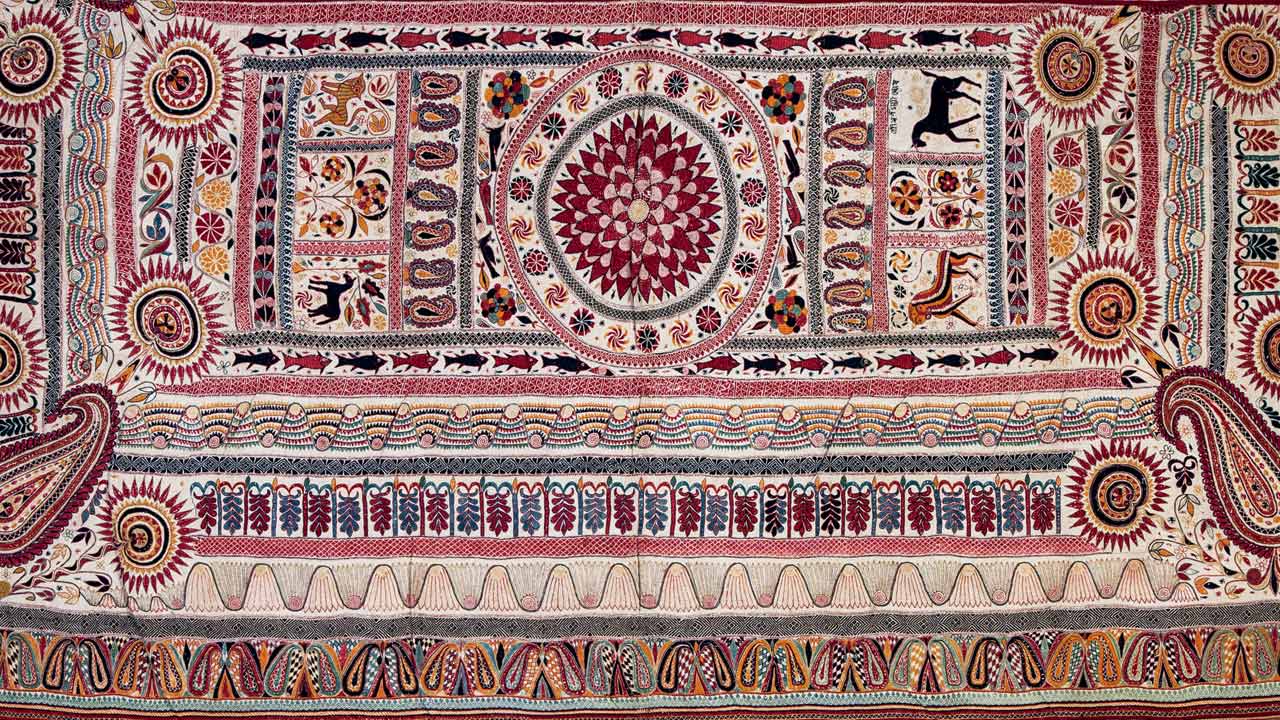

Kantha: A fragment of Partition’s memory

Sujni nakshi kantha, cotton embroidery, 20th century, Bengal. Collection: Weavers Studio Resource Centre, Kolkata

One half of this kantha is missing, symbolising the separation of families during the Partition of India. Kanthas, often treasured as family heirlooms, were also divided as families were torn apart. This half carries the memory of Partition and a deep sense of belonging.

Baluchari: Bengal’s Nawabi heritage

The name Baluchari comes from Balu (sand) and Char (bank), referring to its birthplace beside the Bhagirathi River. Emerging in the 1700s, the Baluchari saree became a symbol of Bengal’s Nawabi heritage, weaving stories of Mughal courts onto silk. The motifs depicted everything from royal Mughal life to British influences, with imagery of steamers, Nawabs, and hookah-smoking elites on trains.

Baluchari saree with motifs of Europeans on trains, woven silk on traditional jala loom in Murshidabad, 19th century. Collection: Weavers Studio Resource Centre, Kolkata

Though it lost favour in the 19th century, overshadowed by styles like Banarasi, the saree was revived in Bishnupur, evolving with new motifs and deeper narratives. Today, the Baluchari saree is more than just fabric—it’s a woven tale of history, culture, and craftsmanship that endures through time.

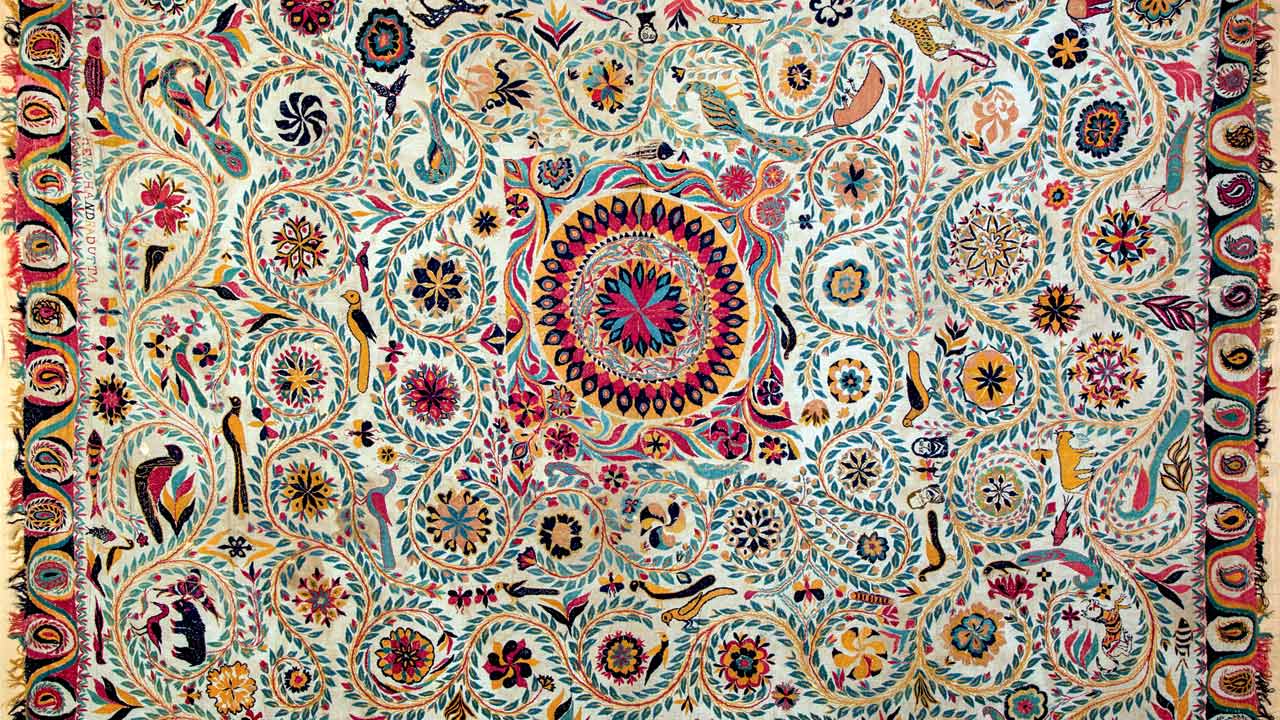

Kantha: Beyond folk art

This kantha blends traditional techniques with elements of Kashida Kashmir embroidery, creating a distinctive fusion. Its large size, likely intended for a bed or canopy, features fringed edges, adding a modern touch akin to designer shawls. A face, possibly inspired by Bengali literary pioneer Michael Madhusudan Dutt, is embroidered by artist Hemchandra Dutt adding intrigue.

Late 19th century nakshi kantha in cotton, hand embroidered with faces of Bengali poet and playwright Michael Madhusudan Dutt in different corners by Hemchandra Dutt (as signed). Collection: Weavers Studio Resource Centre, Kolkata

The design includes a central medallion, an all-over jal (lattice) pattern, and a border of ambi (paisley) motifs, but notably omits the usual konia corner designs. The backstory hints at its passage through generations, possibly due to family separation or financial hardship. With precise symmetry and high-quality materials, this kantha stands out for its craftsmanship, suggesting it was a commissioned piece that elevated kantha beyond its folk art roots.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!