In a new book, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi's son Raghavendra from his first marriage revisits the torment and hurt he faced at the hands of his musician father, who belonged to everyone, but not him

Bharat Ratna Pandit Bhimsen Joshi during a performance at Rang Bhavan, Dhobi Talao

ADVERTISEMENT

I stopped going to Bhimanna for money on a monthly basis after I got a regular job. My younger brother Anand, who was slightly older than 'her' younger son, had to go to him for money needed for Mother's expenses. He had to suffer endless humiliations and angry outbursts. He could never get over the hurt and bitterness that Bhimanna's words caused in the presence of the 'other' family.

Once he wanted to join a college trekking expedition and needed trekking shoes. When he went to ask for money he was humiliated in such rude language by Bhimanna that even his friend Dixit, who was present there and had told me the entire story, could not stomach it. 'Anna should not have done it,' he told me.

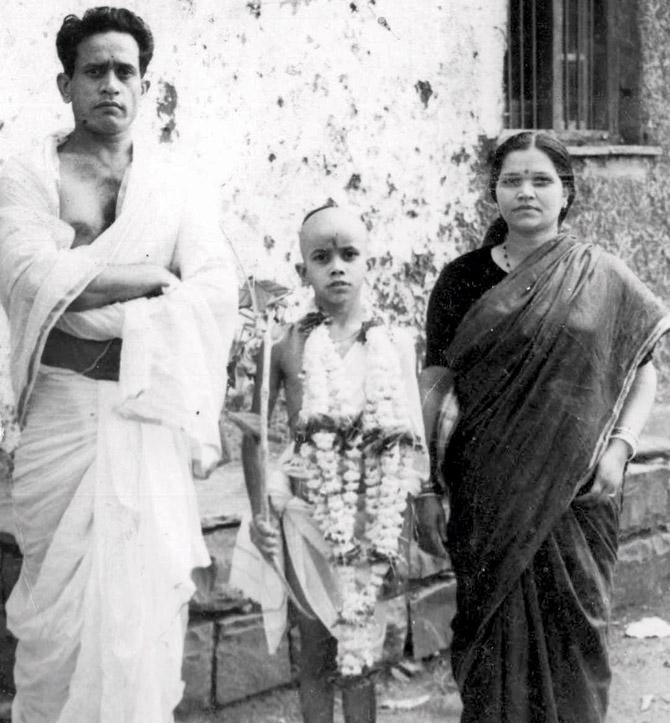

Raghavendra seen here with his parents, Bhimsen and Sunanda, at his thread ceremony in 1955, Belgaum

Bhimanna's 'other' family was squandering his money, including spending on their foreign visits. I could never understand how such a fine person could ever be so partial. When I was with him I crooned his favourite bhajan that went like 'Have compassion for your servants as much as for your sons', but he got irritated and shouted, 'I've done everything for everyone'. The truth was that what he did for his servants he did not do for us — his own children. He even got a house for his servant using government quota. He was angry because he thought that I was hinting at such help for us too.

I had made it a practice to go to him and touch his feet before all important rituals and events. Once I went to see him on the auspicious day of Padva. My stepsister refused me entry into the house saying, 'He is busy giving tuitions'. I pushed my way past her and entered the room where he was teaching a couple of students — Kumar Gandharva's son being one of them — raga Abhogi. He was producing a difficult taan pattern, which was a little beyond the learners' ability, but which I was confident of repeating. I had listened to his Abhogi several times earlier and knew the details by heart. Presently he came out of his trance and looked at me with a warm smile.

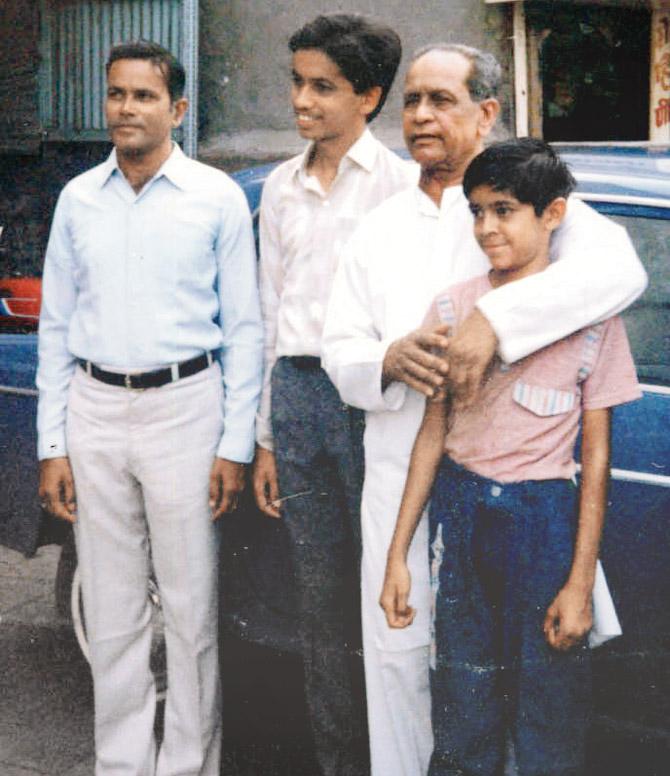

Raghavendra, Rahul, Bhimanna and Atul in front of the first new car in 1989, Pune

I touched his feet and put a large ramphal (a variety of custard apple) from my garden at his feet. 'What fruit is this?' he asked. He said he had never eaten it before. I told him to let it ripen for a couple of days before eating it, and left. My stepsister had by then disappeared. I went to him after a couple of days and casually asked if he had liked the ramphal. 'They kept it in a box and it rotted there,' he said. I was deeply hurt. This was possibly part of the plan to prevent him from feeling any love for us, I thought. 'All right,' he said, sadly. I shuddered to think how those evil people must have tortured Mother with similar wiles and guile.

When Bhimanna abandoned us and went to Nagpur from Badami, he had written a letter to mother in Kannada. It was replete with a deep sense of regret. He had written, 'I have wronged you deeply. I am caught in a vicious net. But I promise that I will never disown you and the children. Please forgive me.' Long after my sisters, Sumangala and Usha, and I had got married, Mother showed the letter to my wife Maya and said, 'Now that the children are married, why should I keep this letter?' And she tore it into pieces. My wife, too, was not mature enough to understand the importance of preserving such documents.

The restrictions on Bhimanna's liberty got progressively stricter, so much so that he would refuse to recognise us at concerts if 'she' was around. He was forced to prevent all information about his first marriage and children from appearing in any public medium. We realized how slavish he had become when he suppressed all reference to his first marriage in a documentary made on him by the eminent cine-writer Gulzar.

My two children — Bhimanna's grandsons — were collegegoing young lads then. How humiliated they must have felt to be left unacknowledged like this! Once Bhimanna was to meet a friend of mine from England. He asked me to see him at his relative's place at Deccan Gymkhana in Poona. When I reached there, my friend was not at home. The host introduced me as Bhimanna's son to the people in the house, but the mistress of the house blared, 'Maybe, but I know everyone and everything at Bhimanna's place from "her".'

I was stunned more by the indecent curiosity about 'everything' in other people's houses than by the refusal to accept me for who I was. I left without reacting and waited downstairs at the door. Whenever I come across such a lack of sensitivity, I remember Bhimanna's favourite bhajan by Sant Kabir 'Sab paise ke bhai' (Everybody claims relationship with the moneyed).

Bhimanna was once suffering from common cold and took a strong course of antibiotics to get rid of it before a performance, but it made him weak. His voice sounded like coming from the depth of a well. He held my hand for a while. As the 'others' were around, he spoke to me only through this touch. 'Get well,' I said, pressing his hand, and left.

He was getting old and caution demanded that the number of performances he gave be limited. In 1996, he fell from the staircase and hurt his spine. For over a month he was bedridden. Again in 1998 he had a fall and broke both his knees.

Added to the problem was the high dosage of antibiotics, which confined him, alone and sad, to his bed upstairs. I met him frequently. One evening when I was with him, the attendant left us. All around lay mounds of litter and junk, making the room look like an attic. Next to his pillow stood a framed photograph of Bhimanna's father and that of God Maruti of Yalgur near Bijapur. I had crossed fifty, and we were with each other, all by ourselves, after years. So I boldly asked him a question that had rankled me all these years.

I asked for permission and said, 'Bhimanna, when you sing Abhogi or Jogiya or Bhairavi, you make the audiences weep. How, then, can you be so hard-hearted with me and with all of us?' Tears began to trickle from his eyes as he tightened his grip on my hand and whispered, 'If you allow someone else to pull your strings, then life is only a cacophony!' He had understood perfectly the question to which I sought an answer.

He was trying to tell me that the greatest loss in such a situation was the loss of one's freedom. I was surprised that such a strong person should sound so depressed. My own grief came from the fact that while he gave everything to everyone so generously, he withheld his music from me. His answer was contained in a short sentence, but there was no end to our suffering.

Excerpted from Bhimsen Joshi, My Father by Raghavendra Bhimsen Joshi; Translated from Marathi by Shirish Chindhade; excerpted with permission from Oxford University Press

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!