Death of the world's greatest chef, Benoît Violier, pulled the lid off the pressure that goes in to serve perfection. If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen doesn't apply to Mumbai's high-tension star eateries

Director of Bellona Hospitality Paul Kinny serves up an Asian spicy pizza at Craft Deli, at Kurla during lunch hour.

Uptil 11.45 am, the kitchen at Kurla's Phoenix Marketcity's six-month-old eatery, Craft Deli seems like the dining area it accompanies — the empty tables lend their sense of calm to the staff on the other side of the counter.

Uptil 11.45 am, the kitchen at Kurla's Phoenix Marketcity's six-month-old eatery, Craft Deli seems like the dining area it accompanies — the empty tables lend their sense of calm to the staff on the other side of the counter.

ADVERTISEMENT

Director of Bellona Hospitality Paul Kinny serves up an Asian spicy pizza at Craft Deli, at Kurla during lunch hour. Pics/Bipin Kokate

Director and chef Paul Kinny, who heads 10 kitchens in the city for Bellona Hospitality, begins the day at 9 am with a short de-briefing of his 13-member staff, brought to an army-esque alertness under his stern gaze.

The Kitchen Order Ticket (KOT) — the machine that transmits the order to the kitchen, once the server logs it into the computer — has just beeped: Two beef burgers, parcel. These will go with a Spanish omelette and fries, the slip reads. Now, it feels like we're watching a hyperlapse video.

The 13-member staff at Kurla's Craft Deli has to cater to 50-100 guests at a time: while dinner is the busiest time, lunch serves a unique challenge because no diner wants to spend more than 40 minutes over a meal in the middle of a work day

The team swings into action, even as the KOT stutters again. "One garlic bread, artisinal rigatoni, veg pizza, Sriracha chicken wings — make it spicy for Table No. 2," shouts Kinny, who is at the 'pass' for the day. The chef at the pass is the kitchen equivalent of an orchestra conductor. "He picks up the order tickets, and 'barks' them to the team. Today, that's me. I will continue barking the order till I hear a 'Yes, chef'," he says. The team barks back in chorus "yes, chef!".

We follow the first order from scratch to table — the cold section prepares the salad, the grill section makes the patties, and the hot section makes crunchy fries. "The hot section can scream at the cold section for a delay but not vice versa. Also, the cold section must work the fastest, for you cannot make hot ingredients wait," says Kinny, calling out to the server to pick up the order for Table No. 2. "I cannot let the plate sit on the counter even for 10 seconds. The quality of a dish begins to deteriorate from the moment it is ready."

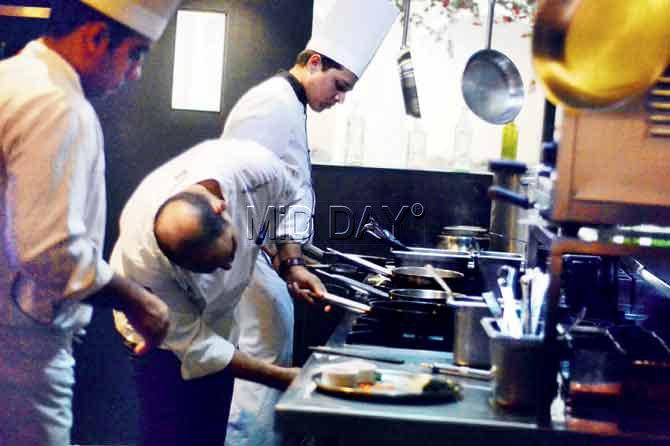

At Pa Pa Ya the chefs were busy concentrating on the day’s menu and wouldn’t so much as lift their heads to answer questions. Deadlines are sacrosanct in every kitchen, and daily hurdles are many

Welcome to the pressure cooker. With tourism on the rise and even the average middle-class family enjoying more expendable income, the hospitality industry in India has seen a boom in the last 15 years. A new restaurant opens in Mumbai every other week. Quality cannot be compromised and, sometimes, even being deigned the world's best chef, isn't cure enough.

Last month, Benoit Violier, who ran the three-Michelin-starred Restaurant de l'Hotel de Ville near Lausanne in Switzerland, allegedly committed suicide (no note was found). It's reported that he fell for a £1million wine scam that put him in considerable financial trouble, despite the success of his restaurant.

At Craft Deli a gas connection that suddenly went off caused a seven-minute delay

Zorawar Kalra, founder and MD of Massive Restaurants Pvt Ltd, which owns some of the country's top gastronomical destinations such as Masala Library and Pa Pa Ya, said the best way to gauge the pressure that chefs, managers and waiters undergo as you dig into your sushi roll, is to spend a day at a kitchen.

Essence of time

Lunch becomes a busy hour at the Asian gastrobar, Pa Pa Ya, where the kitchen is sectioned off into bits keeping with the menu. In one corner, is chef Nikhil Amburle, rolling out sushis in under a minute, even as he coordinates with ground staff on the orders, and interacts with curious eaters who need help identifying their chorizo octopus from their tuna and scallops. One corner is for the dimsum and pizzeria. At the far end is the dessert corner, where a baker is making chocolate bombs, and at the centre are two chefs working on the central wok.

Chef Gresham Fernandes, Impressario Group

Executive chef Sahil Singh is on the floor answering diner queries like he is responding to a well-prepared viva voce examination. But, his focus remains on the caviar he is working on. When a server complains of delay in a dish, his curt response is, "Time pe punch karo, time pe ayega." Time, all chefs will tell you, is of essence. Diners, especially those who step out of office on a lunch break, have 40 minutes in which they can place an order, eat and pay the bill.

Which is why, when the gas goes off suddenly, back at Craft Deli, hell breaks loose. "Ek ka gaya ya sab ka?" Kinny asks aloud. "Sab gaya, chef," says another chef, without stopping the plating he has at hand. Even this seven-minute delay has put things off-track. The team has to pick up speed. With one person short on the serving staff, 33-year-old restaurant manager Nikhil Bangera, chips in to ready the parcel order. "And, when frustrated, we can't yell at customers. So, one tends to lose their tempers inside the kitchen," says Bangera. Tempers and verbal abuse fly high. But, it's all in a day's work.

Attrition brings in manners

In November 2014, a report in The Telegraph, UK, pulled the lid off kitchen aggression: A group of top chefs in France called on their peers to stamp out the culture of violence in the kitchen — physical violence (seen flying plates in Hell's Kitchen?), hazing and insults.

In India, things began to change in 2011 when professionalism and competition stepped in. Where once burns and bruises would be a rite of passage in the kitchen, expletives are as far as temperamental bosses will go. "There are women in kitchen now, so things are more civilised. The biggest pressure is retaining people.

Earlier, there weren't as many restaurants so a staffer would take abuse from a senior. Today, a person will walk out for a raise of only R2,000," says Gresham Fernandes, group executive chef — fine dine, Impressario Group.

There have been newcomers, Fernandes says, who have lasted as little as a day. Most drop out in the first year. Chef Vernon Coelho, who taught at the Institute of Hotel Management for 34 years, says less than 50 per cent out of a batch of 100 end up as chefs or restaurant staff. "The first two years are tough to crack. The stress is something they can learn to deal with only if they have a passion for the profession," he says.

That the job leaves you with little personal life doesn't help. Here, 12-hour work days are the norm. Sous chef Ajay Samtani has made his peace. "The real test will be when I get married. I don't know how I will manage a personal and professional life then," he grins.

"Most can't cope. They opt for jobs that will give them a balanced life," says Coelho, who promises that "as you climb up the ladder it gets easier", but only because you become used to the pressure. Institutes try to introduce their students to the pressure during the course. Deadlines remain strict, hygiene standards have to be met and mock kitchen classes are held.

But, even the pressure-cooker course can't prepare one for the many rungs of the ladder that you need to climb to be, as Kinny puts it, "the rockstar chef". An average kitchen in a five-star or a plush dining spot has four commis chefs and four junior chefs. The numbers, of course, change depending on the specialty cuisine that restaurant serves. The rank right below the executive chef is that of the sous chef's. And, it could take a commis chef over a decade to reach that coveted rank, unless their chef "sees a spark in them and decides to mentor them".

That a commis chef's salary begins at R7,000 a month (if they haven't been to a culinary school) or at R15,000 (if they have), makes the wait to R50,000 (a ball park figure) pay scale of a sous chef that much longer. And, if your aim is to run a kitchen of your own, then it could take a couple of years or more for someone to pick you up and make you an executive chef.

It is about the money

Kinny says his day begins with the previous night's sales report, along with guest feedback reviews and accidents. The 120-seater Craft Deli sees about 50 diners coming in for lunch daily, which touches 90 a night, on a weekday. The weekend numbers climb to 120 in the day and 150 in the night.

For a new restaurant, that's a good number. After all, with rentals high in Mumbai, besides other licencing costs etc, profits are not easy to come by. "No one makes a profit in the first year, and the gestation period to make a profit, is three to four years," says Fernandes.

And, in the world of social media, one bad review can discourage 100 people from coming to your restaurant. "Everyone is a masterchef, we are mere chefs," smiles Kinny. The customers' various demands don't help ease the pressure. Dennis Wu, manager at Pa Pa Ya, says, "Often, customers want to add and remove ingredients [from a dish]. At an hour when orders are pouring in, this disrupts momentum."

Liquid crutch

Deadlines with no margin for error, long work days with added pressure during festive periods, varying payscales with tough scope for career growth and a very competitive industry to stay afloat in, make for a dangerous cocktail. Hence, the day's pressures are often drowned in alcohol.

Substance abuse is the dark result of the industry's pressures that management has had to come up with policies to deal with. "It's a joke, that after serving all day, it's 'peene ka time' for people from the hospitality industry. Janta Bar in Bandra and a few others in Dadar are watering holes that turn into board meetings," says Kinny, adding that, however, restaurants now have a strict policy against turning up tipsy at work.

Wu adds, "If anyone walks in tipsy or drunk, we send them back." Besides just professionalism, being tipsy at work is hazardous. "He could slip, cut or burn himself. I give three warnings, and then fire the person," says Fernandes.

Kinny adds that smoking is a big no too. "In my early days, my senior chef did not allow me to eat pickle, for it blankets the taste buds. So does smoking. I don't allow my chefs to smoke either." Coffee, energy drinks and tea are more acceptable addictions.

What makes the gruelling life worth it? It's a questions that begs an answer. Singh puts it simply: "As a team, everyone wants the customers to walk out with a smile. That makes it worth the effort."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!