A colonial crime involving a young Bombay corporator, a gorgeous courtesan and a royal from the house of Holkars, has become the subject of a new book that explores how the social and political movements of the time, influenced the investigation

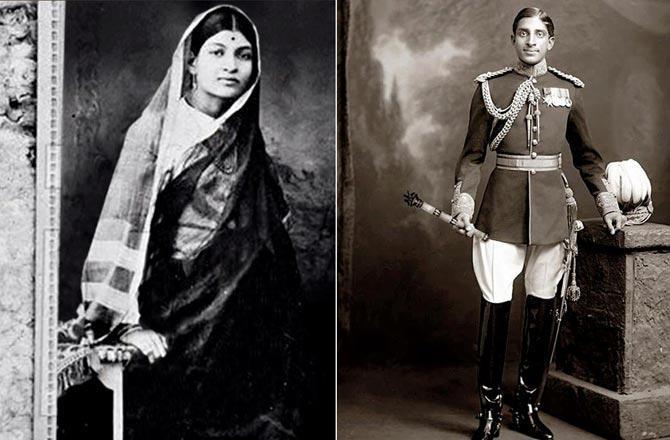

Mumtaz Begum; (right) Tukojirao Holkar III. Pic/Wikimedia Commons

In Mumbai, crime is an everyday thing. Its nature varies, and so does the scale, but the city mostly bears this aberration, often tolerating it. Yet, ever so often, there comes a case, which rattles the foundation of a society and its polity. Ninety-six years ago, on the evening of January 12, 1925, the cold-blooded murder of a wealthy businessman and young corporator of the Bombay Municipal Corporation, Abdul Kadir Bawla, and the abduction attempt of his lover Mumtaz Begum, in the posh Malabar Hill area, led to a cataclysmic chain of events that shook the colonial port city, eventually forcing Maharajadhiraja Raja Rajeshwar Sawai Shri Tukojirao Holkar III, the Maharaja of Indore, to abdicate.

ADVERTISEMENT

This incident is at the heart of a soon-to-release book, The Bawla Murder Case: Love, Lust and Crime in Colonial India (HarperCollins India), by Dhaval Kulkarni.

Dhaval Kulkarni outside Abdul Kadir Bawla's residence in Girgaum Chowpatty, which also houses the Islam Club

The Mumbai-based writer and journalist first learnt of the murder, when he read a column by historian-writer Manu S Pillai on the alleged involvement of Tukojirao Holkar III in the crime. "Some months later, in December 2019, I met Rohidas Dusar, a retired deputy commissioner of police, who is also a prolific chronicler of the history of the Maharashtra police, for an unrelated story. During the course of our conversation, this particular case cropped up. His book on the Bawla murder case is a deep dive into the investigation. Later, Deepak Rao, a walking encyclopaedia on the city's history, also helped throw light on it. As I started digging deeper, I realised that this was not an ordinary crime story," shares Kulkarni, in a telephonic interview.

Abdul Kadir Bawla

Bawla was just 25, when he was shot dead by a group of men that had surrounded his six-cylinder Studebaker after colliding with his car, near the bishop's bungalow in Hanging Gardens. Mumtaz, who had joined Bawla for an evening drive that day, was attacked, with deliberate attempts made to disfigure her face, before the assailants dragged her out and tried to escape with her. Their plans were foiled by a group of lieutenants, who were passing by, and they, at risk to their own lives, saved Mumtaz. Bawla was rushed to JJ Hospital, where though he underwent surgery, succumbed to haemorrhage from gunshot injuries to his liver. What followed was one of the most rigorous and foolproof police investigations—under then commissioner of police, Patrick Kelly—the city had ever seen, and one based purely on "circumstantial and material evidence, and human intelligence".

During the investigation, which Kulkarni says had become the "talk of the country," it was learnt that Mumtaz, a courtesan, was formerly the mistress of Tukojirao Holkar III, and had fled Indore after a disagreement with Shankarrao Gawde, a senior official in the Indore durbar. While Shankarrao was incarcerated, Tukojirao had ordered his mistress, on several occasions, to return, but to no avail.

The site near Hanging Gardens in Malabar Hill, where the murder most likely took place

The arrest of Major General Sardar 'Dilerjang' Anandrao Gangaram Phanse, the nephew of Shankarrao, opened a can of worms, revealing how the entire crime had been plotted in Indore, with the sole purpose of kidnapping Mumtaz. A media trial of astounding proportions followed, where the Bombay press "ran amok over the Bawla case with its tinge of romance and gallantry, with the shadow of a ruling prince in the background". The trial even drew the attention of Ruttie, Muhammad Ali Jinnah's Parsi wife—Jinnah was defence lawyer for Phanse—who "did not move out of the courtroom as long as the trial lasted, and was possessed by a desire to help Mumtaz". "The kind of people involved in the case, generated a lot of excitement," says Kulkarni. "What was interesting is that back in the day, the press was dominated by a certain community [Brahmins, with their access to education and learning, took up jobs as editors and journalists]." The Holkars, being pastoralist Dhangars by caste, were non-Brahmins. "When it came to taking a position on people of other communities, there was an element of bias that crept in," he adds.

Tukojirao Holkar III, however, found an ally in anti-caste activist, social reformer and journalist Prabodhankar Keshav Sitaram Thackeray, father of Bal Thackeray. "Thackeray [in his editorials] pointed out that the accused refused to name Tukojirao even when they had been sentenced to death. He got so invested in the case that he wrote three books on this case; even in his autobiography [Majhi Jeevangatha], he dedicated four-and-a-half pages to it. The case also hence, became about Brahmins versus non-Brahmins."

For his book, Kulkarni pored over court papers at the National Archives of India, in New Delhi. He also succinctly stitched together the back-story of the Holkars, the Gaikwads of Baroda, the reformist movement in the region spearheaded by the likes of Lokmanya Tilak, and the Shuddi movement led by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, to understand the micro-histories that overlapped with the murder. The way the people and the press responded to the case, had a lot to do with the contemporary society then, he feels. Tukojirao later married an American, his third wife, and their union was supported by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. "As a student of social movements, history and society, I found this fascinating. You cannot see this murder in isolation. A lot of things happened before and even after."

To many, the case seemed like a good excuse for the British government to get rid of Tukojirao, who was becoming a pain in the neck. He was given an ultimatum—to either abdicate or face an inquiry. He chose the former in 1926, but clarified that it was "not the consciousness of guilt" that influenced his decision. "I am perplexed as to what might have actually happened, because the truth is ultimately subjective. But as [Bombay High Court] Justice LC Crump rightly pointed out, the attack clearly originated in Indore. Again, the question is who would have wanted to abduct Mumtaz and get her back to Indore other than Tukojirao himself," says Kulkarni.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!