Creative geniuses Aabid Surti and son Aalif discuss what it means to revisit a novel that's too close to home, and which for long, has been denied a good translation

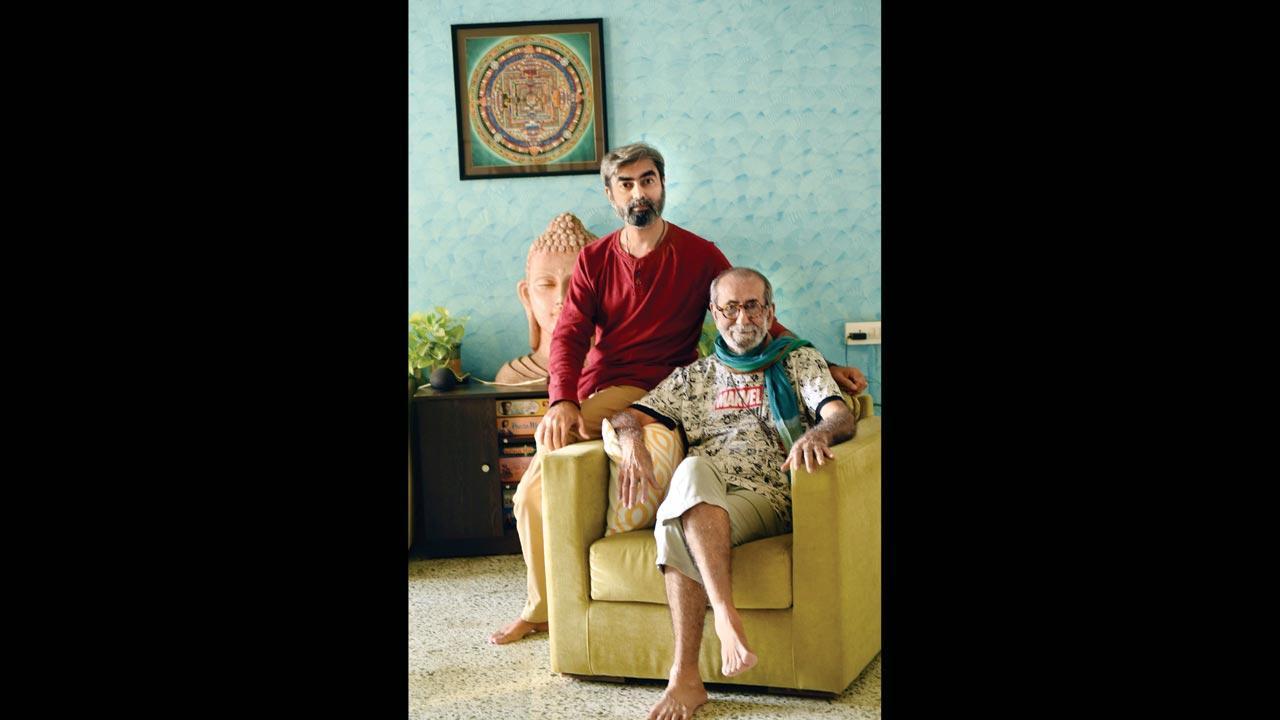

Producer-writer Aalif Surti hopes to translate more of his father Aabid’s books in the near future. His first translation was Sufi: The Invisible Man of the Underworld, which he didn’t take credit for. Pic/Sameer Markande

When do you really become your father’s son? At birth, or when your achievements match his, or the moment when his vision becomes your own? Sitting with veteran writer-painter-environmentalist Aabid Surti and his producer-writer son Aalif at the latter’s airy Andheri West residence, this question comes to mind more than once.

ADVERTISEMENT

There is something characteristically similar about the two: their self-effacing demeanour, the soft cadence of their voices, how they sit on the couch—mostly cross-legged—and also, the manner in which they sip their tea, very slowly. If it were not for age, it would be difficult to tell them apart, except that 86-year-old Aabid appears more chic in a Marvel T-shirt completed by a blue muffler. The genius behind the Indian superhero Bahadur, says his son, “is a fan”.

Aalif Surti

The former creative head of Fox Star Studios India, Aalif, 47, has been keeping himself busy producing movies, writing web shows, and reading and translating his father’s work. The bookshelf, which mostly has Aabid’s Hindi and Gujarati novels, makes this plain evident. The day we meet, Aalif’s English translation of his father’s famed Gujarati novel, Vasaksajja, first published in the early 1970s, has just hit stores. A biographical account of commercial sex worker Kumud (name changed), who from the alleys of Kamathipura, Bombay’s red-light district, in the 1960s, rose to become an actress in several leading films, Cages: Love and Vengeance in a Red-light District (Penguin Random House), is the second book translated by Aalif, a former film journalist, but the first one he has taken credit for. “I think I got acquainted with dad’s work quite late...embarrassingly late, actually,” Aalif admits. “And the reason for this was mostly because there weren’t many English translations of his work.”

“Dad grew up in abject poverty. He used to sell sweets in Dongri, and studied at a Gujarati-medium school. To his credit, the first thing that he did for us children was to buy a one room kitchen in Bandra—it’s all that he could afford then—so that my brother could receive an English education.” His decision to finally sit down and translate Aabid’s works, he says, was because he wanted to reciprocate in kind.

Aabid Surti

“I am not a professional translator. But I’ve read the few-odd English translations of his work, and I know they weren’t great.” None of them, he says, captured the authenticity of his work.

Aabid, whose 80-odd books have been translated into Marathi, Urdu, Kannada, Telugu, and Bangla among others, interrupts, “Some of the translations of my previous books have been horrible. You cannot imagine the kind of work that is out there. There is a certain kind of insincerity, and because I read English, Marathi and Urdu, I know.”

One of the problems with translating his father’s work, feels Aalif, is his “deceptively, simple style of writing”. “He writes these very short, simple sentences. And

somehow, because of his vast experience of writing, that simplicity adds up to something fantastic. When you are a translator, it can be unnerving.”

Aalif came across Cages, five years ago. The Gujarati work was written somewhere in the early 1970s, when Aabid was researching a piece for a magazine, Sarika, edited by well-known Hindi scriptwriter and author Kamleshwar Prasad Saxena. “He wanted me to write a feature on the red-light area of Kamathipura. I was living in Dongri then, and it was just a stone’s throw away. A taxi driver led me to a broker, who introduced me to sex workers there. I may have interviewed about 60 to 70 of them. All their stories were almost the same—many were forced into prostitution or sold by someone they trusted. Among them was this one woman, who had a different story.

She told me, ‘This is my pesha. My mother was one, and so was my grandmother. And what’s wrong with that?’” Her story stuck with Aabid. When he eventually filed his story for the magazine, he kept her account aside. “This was a subject for a novel. I continued to stay in touch with her, and did many interviews.” That’s how Kumud was born. Incidentally, Aabid is a character in the book, too. “When you read the book, you realise how everybody was using everyone. Kumud, who was exploited by many, was using me [to tell her story]. In a way, I was using her [for the book and to make money].”

Kumud did go on to become a film actress, doing several films. Her identity was never revealed. “I liked the graph of this book,” shares Aalif, who recently produced the Tamil film Soorarai Pottru starring Suriya, which has joined the Oscar race in the Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director categories. “The way dad created the world of this area was fascinating. At the top of the hierarchy was the underworld don, who gave protection to the brothels. Below him was the madam, the queen of the brothels. Then came the fair-skinned sex workers, who they called gori chamdi; they operated out of the air-conditioned rooms. After them, came the women who did their business out of cages. Below these, are those who operated on streets. The lowest in the rung, were those who worked in the dark, because they are unpleasant to look at, and preferred not to be seen. Kumud started working in the dark, and then went on to take an underworld don, before she moved up the ladder. It was an amazing David and Goliath story.”

One of the most important points that his father made in the book, feels Aalif, was whether sex workers had the right to say no. “That is the linchpin for me. Just because she is okay with her profession, does it mean that if someone forces himself on her, it would not be construed as rape? Her [Kumud] stance on it was interesting. To me it’s a very modern book.”

The translation happened over several weeks, and with Aabid coming over almost every weekend to spend time with his son, they were able to discuss the best way to tell this story. “We have had our arguments, but ultimately my son convinces me,” he says.

Aabid’s writing journey began by sheer accident. Nursing heartbreak while at JJ School of Art, he started pouring his thoughts out on paper. “I didn’t know what I had written, because I had never read a book before. But jo mere andar ki jhunjhlahat thi, woh nikal gayi [It helped quell the anxiety I was feeling inside of me].” A local kabadiwala, who used to visit the chawl where he lived, got curious about the reams of pages he had stockpiled. “He took it back home, read it and told me that this should be published.” The recycler put him in touch with a Gujarati publisher, Swati Prakashan, and since then he has never looked back. All through his life, he took up many different jobs—he was also fourth and third assistant in several films, became cartoonist and held art exhibitions—and for the last decade and more, has been spearheading the water conservation movement through his foundation, Drop Dead. In 1993, he was awarded the President’s Medal for literature for his collection of short stories, Teesri Aankh. Aalif, who himself never followed a single career path, looks at his father’s journey as inspirational. “For dad, creativity is a way of life, and that’s what he taught us. He told us, ‘Whatever you do, do it with a creative eye. Find the fun in life.’ Our creative paths are never fixed, thanks to him.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!