A new anthology of banned literature from colonial India draws attention to print technology and the practices of reading and writing as weapons of war against the colonial administration

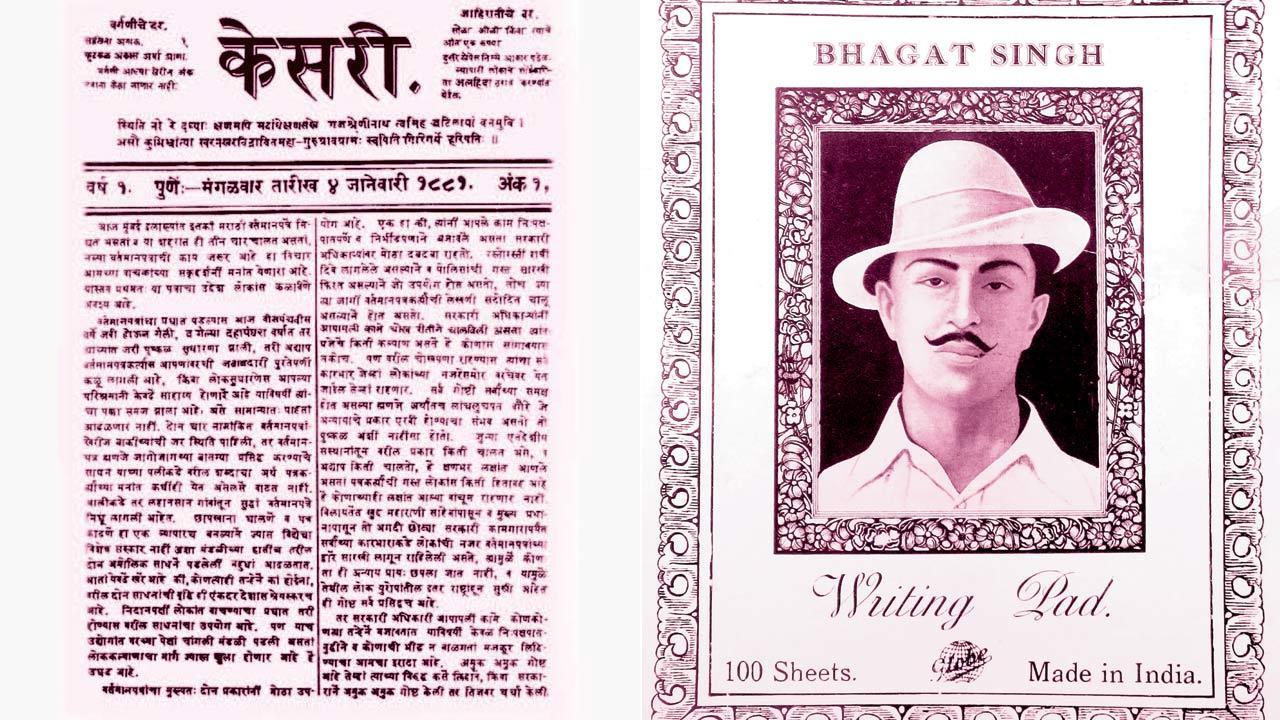

The front page of Tilak’s Kesari, January 1881 and a banned Bhagat Singh writing pad

As a historian, I am sensitive to anniversaries of important events, and to techniques and of commemoration… India’s 75th year of independence was definitely on my mind when I selected the 75 pieces,” Dr Devika Sethi, assistant professor at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, tells us over an email interview. Banned & Censored: What the British Raj Didn’t Want Us to Read (Roli Books, R1,295), her new book, is a wide-ranging anthology of banned literature from colonial India whose 75 texts she has selected and introduced.

ADVERTISEMENT

While the landmark academic history of censorship in colonial India was published in 1974 by American historian N Gerald Barrier and there have been other anthologies of banned literature associated with Bhagat Singh and proscribed patriotic poetry, Sethi explains that what sets this title apart is its collection of “banned poetry and prose from books, pamphlets, posters, newspapers, journals and even a dhoti!” Selecting material deemed “seditious” rather than “obscene” or “hate” speech, illuminating seminal moments and themes from Indians’ anti-colonial struggle in the 20th century, and balancing writings by famous nationalists of all political persuasions with those by “ordinary” Indians reluctant even to be identified with their own texts for fear of reprisal were some of the decisions that drove the selection.

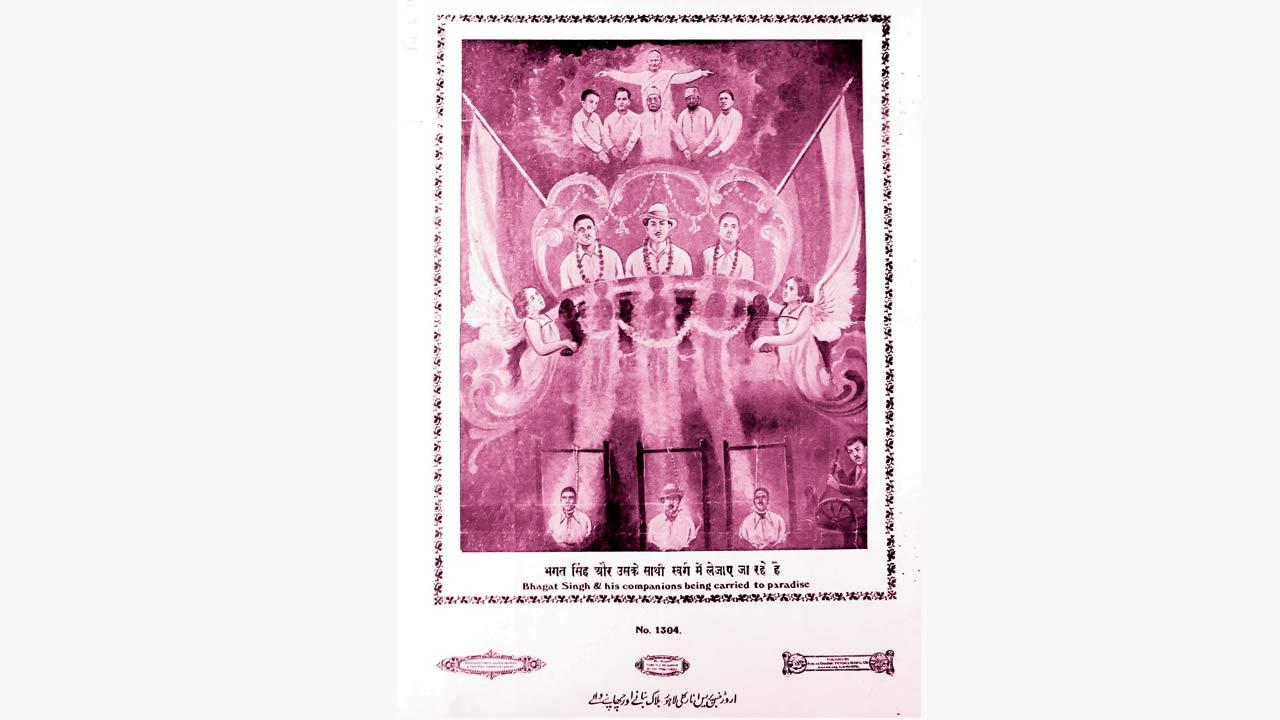

A martyrology poster published by a press in Lahore shows revolutionaries Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev making their way to heaven after the hanging. Pics Courtesy/Roli Books

A martyrology poster published by a press in Lahore shows revolutionaries Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev making their way to heaven after the hanging. Pics Courtesy/Roli Books

The assembling of the pieces pointed towards an increasing sense of pan Indian nationalism from the early to the mid-20th century, Sethi points out. At the same time, there was a realisation that “not all banned literature needs to be celebrated–some of it can be extremely violent, or echo regressive trends in society”.

Incorporating material originally published in English and from nine other Indian languages, the book’s scope ranges from excerpts from Lala Lajpat Rai’s banned Young India which was described in a review as “probably the most damning indictment of the loyalty of the Indian politician that has ever been written” to Motilal Nehru’s pamphlet A Message to Kisans explaining the Non-Cooperation campaign to rural peasants.

The 1908 kesari articles | The Marathi weekly described as expressing “the most extreme views and [enjoying] the largest circulation of any vernacular organ in India” was started by Bal Gangadhar Tilak in 1880. In June 1897, he was sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for verses published in the journal. The Kesari again came to the government’s notice in 1908, when its circulation was estimated at 20,000 copies. At this time, Tilak was also in the sights of the government with an official of the Government of Bombay terming him “by far the ablest and most dangerous of the rebel party in this country”. In June 1908, Tilak was arrested in connection with two articles, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah appeared as his counsel during the bail hearing. In his address to the jury in his own defence, he stated that his views had been mentioned in pro-British newspapers and expressed scepticism regarding the reliance on translations of the original Marathi articles. The context in which the articles were published, the first one only 12 days after the Alipore bomb outrage, was also considered significant by the judge. The jury found Tilak guilty and his conviction caused a furore.

Devika Sethi

Devika Sethi

Hind swaraj | Hind Swaraj, written on board a ship in 10 days in Gujarati and in the form of a dialogue between two Indians subscribing to different viewpoints, was first serialised in two parts in Indian Opinion, a weekly journal edited by Gandhi, and then published in booklet form. It was banned by the Government of Bombay in 1910 for being anti-British and seditious. Despite the ban, several editions of the work were published subsequently in their English translation (by Gandhi himself). Unlike his contemporaries, Gandhi chose not to accept swaraj in terms of political self-government alone but gave it a moral dimension, by interpreting it as ‘self-rule’ or self-restraint in a much broader sense. Gandhi relied on the works of Western critics like Tolstoy, Emerson, Ruskin and Thoreau. But Hind Swaraj was equally critical of Indians, with Gandhi writing, “The English have not taken India; we have given it to them.” An English translation of the book was also proscribed on grounds that “this book is undoubtedly revolutionary; it is in the form of a dialogue between the ‘editor’ and the ‘reader’ ingeniously constructed so that the editor always appears to be on the side of moderation as compared with the reader who is carried away by his feelings”.

Yugantar circular | Issued by the Hindustan Ghadr Party in 1913, the circular was sent to India in February 1913, but the previous month itself the Criminal Investigation Department had information that a pamphlet had been prepared by Har Dayal who was at the party’s helm on the significance of the bomb and sent by him to Shyamji Krishnavarma in Paris. Madame Cama was believed to have 1,500 copies of it with her for circulation. The original pamphlet was in English. The pamphlet contained a paragraph severely criticising moderate Indian politicians, comparing them to dogs who had been thrown bones by the British.

Poems and writings remembering revolutionaries | The sensational events of the late 1920s and early ’30s inspired publicists (and activated censors) enormously for years to come. Several key events form the framework of reference for these banned publications. The assassination of Assistant Superintendent of Police John Saunders by Bhagat Singh and Shivaram Rajguru in 1927; the lobbing of two bombs inside the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi by Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt in 1929; the Lahore session of the Congress where the Purna Swaraj (Complete Independence) resolution was passed; and the attempt by Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) members to assassinate no less than viceroy Irwin himself by bombing his train. Chandrashekhar Azad, member of the HSRA, who was wanted by the police for his role in the Kakori train robbery as well as for the killing of a police official, was surrounded by the police in a public park in Allahabad where he died in 1931. On March 23 that same year, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev Thapar were hanged for the killing of JP Saunders. The deaths of these young revolutionaries electrified the country and volumes can be filled with the texts composed and circulated for years afterwards, in all parts of India, about their life, work, and manner of death.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!