...Indian cricket lost Syed Hyder Ali, one of the most enduring domestic toilers, whose brand of left-arm spin for Uttar Pradesh, Railways, North and Central Zone fetched him 366 first-class wickets

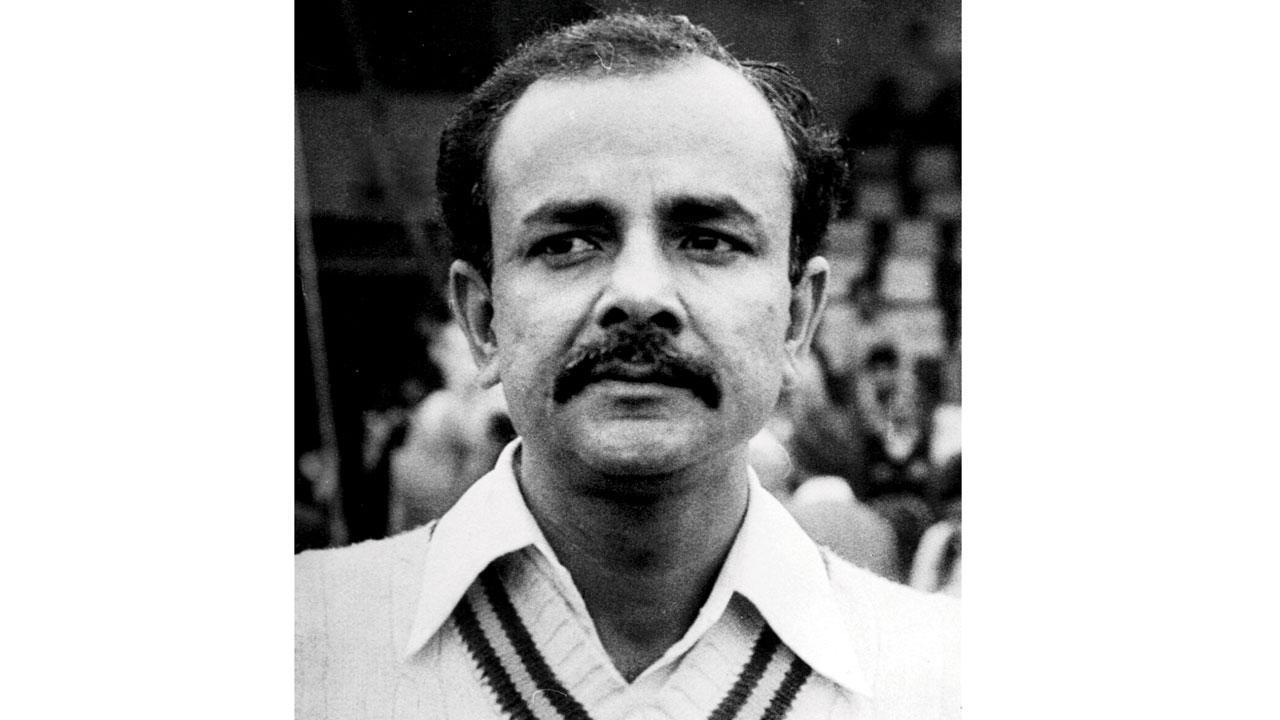

Hyder Ali, who troubled batsmen with his accuracy. PIC/MID-DAY ARCHIVES

Early this month, while Indian cricket was immersed in how far will India progress at the T20 World Cup, an achiever from another format of the game departed the scene just like he graced it—unnoticed and unheralded.

Early this month, while Indian cricket was immersed in how far will India progress at the T20 World Cup, an achiever from another format of the game departed the scene just like he graced it—unnoticed and unheralded.

ADVERTISEMENT

Syed Hyder Ali, 79, the erstwhile Railways Ranji Trophy left-arm spinner and batsman passed away on November 5 in Allahabad while battling a prolonged illness.

A total of 366 wickets in 113 first-class games across 22 seasons, starting off with Uttar Pradesh in 1963-64, provides one a good reason to believe that he should have played for the country. But just like Padmakar Shivalkar and the late Rajinder Goel, that great exponent of left-arm spin Bishan Singh Bedi proved to be too illustrious to displace.

Rajinder Singh Hans, the former national selector, who himself could have played for India through his spin exploits for Uttar Pradesh, told me on Tuesday how Hyder deserved higher honours. “He was dangerous on a helpful track, but he could also turn it on any surface. He was a gentleman, ever-willing to throw in a word of advice,” Hans remarked. He recalled helping Central Zone beat East Zone in the 1977-78 Duleep Trophy quarter-final at Jaipur, where Hyder and Hans claimed 17 of the 20 East Zone wickets to fall.

Central didn’t win the Duleep Trophy that year. West Zone did. But Hyder figured in the North Zone team that won the Duleep Trophy in 1973-74 under Bedi.

Venkat Sunderam, the former Delhi opener, recalled how Hyder was run out in controversial circumstances during the semi-final against West Zone at Pune. “Hyder was batting with Surinder Amarnath. He pulled one through mid-wicket and the umpire signalled four. But Ramnath Parkar chased it and indicated that it was not a boundary. Parkar threw the ball to the wicketkeeper [Suhas Talim], who whipped the bails and Hyder was declared out by the leg umpire [for 12].”

Sunderam also touched upon Hyder’s good nature and appetite for hard work, which included seven to eight hours of practice on non-match days.

One of the more memorable games for Hyder was the 1972-73 Ranji Trophy quarter-final clash against Tamil Nadu at Chennai. He claimed three TN wickets as the hosts were bowled out for 206. A feeble response of 132 didn’t help the Railwaymen, but Hyder’s 7-23 in Tamil Nadu’s second innings gave the visitors a chance. Sadly, Railways were dismissed cheaply again on a spiteful pitch and lost by 110 runs. The match ended inside three days with Hyder staying unbeaten on 30 out of his side’s total of 88.

Chennai offered Railways a chance of a domestic cricket high yet again many years later, in 1988. Hyder was still part of the team—this time as a 44-year-old captain—in a Ranji Trophy final against TN, an advancement caused by a victory over a strong Delhi side on quotient in a rain-affected semi-final. At Chennai, Mumbai-bred left-hander Naresh Churi scored a hundred at one-drop, while the prolific Yusuf Ali Khan missed his by 13 runs. The rest of the batting crumbled to future India spinner M Venkataramana (7-94) and Railways totalled 317. Their second innings effort was worth only 248 after TN piled up 709 with Robin Singh, another future India player from TN, hitting 131 and leggie Laxman Sivaramakrishnan smashing 101 at No. 7.

Often, Hyder would ask Churi to bring the Mumbai attitude to the fore. Churi told me on Tuesday: “Hyder bhai respected Mumbai cricket a lot. That’s why he always urged me to show the Mumbai side of me. We used to chat a lot and I remember him telling me that he didn’t play the Ranji Trophy beyond the quarter-final stage. The 1987-88 final was the farthest Railways teams of his generation reached.

“He remembered that they once bowled out Hyderabad led by ML Jaisimha, for 50 in the first innings [1975-76 Ranji Trophy pre-quarterfinal at Hyderabad], but they still ended up losing—bowled out cheaply in the second innings [for 76].”

The 1987-88 Ranji Trophy final was Hyder’s last first-class game. He continued to serve Railways as an administrator and selector. Amrit Mathur, the former Indian team manager, who at one time was secretary of the Railways Sports Board, messaged me his tribute to Hyder the other day. “Hyder bhai was one of his kind, an old school gentleman cricketer. He bowled cleverly…flighted, loopy and had a sharp cricketing mind. An inspirational figure for youngsters, he was deeply respected by both colleagues and opponents,” stated Mathur.

Delhi’s Karnail Singh Stadium, which can be called the base of Railways’ cricket, was like a second home to Hyder. The decision to observe a moment’s silence during Railways’ warm-up fixture against Jammu & Kashmir there on November 6, was a fine gesture. But naming an enclosure after Hyder, who gave the best years of his life and beyond for Railways cricket, would be particularly meaningful. It’s not only Test legends who deserve to be honoured with their names on stands, but also those like Hyder who help build a game and keep breathing life into it.

mid-day’s group sports editor Clayton Murzello is a purist with an open stance.

He tweets @ClaytonMurzello. Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!