A new book delves into the quaint and lesser-known narratives that run parallel to the popular Ramayana, like the one sung by Kerala’s Malabari Muslims, demonstrating the epic’s acceptance across cultures

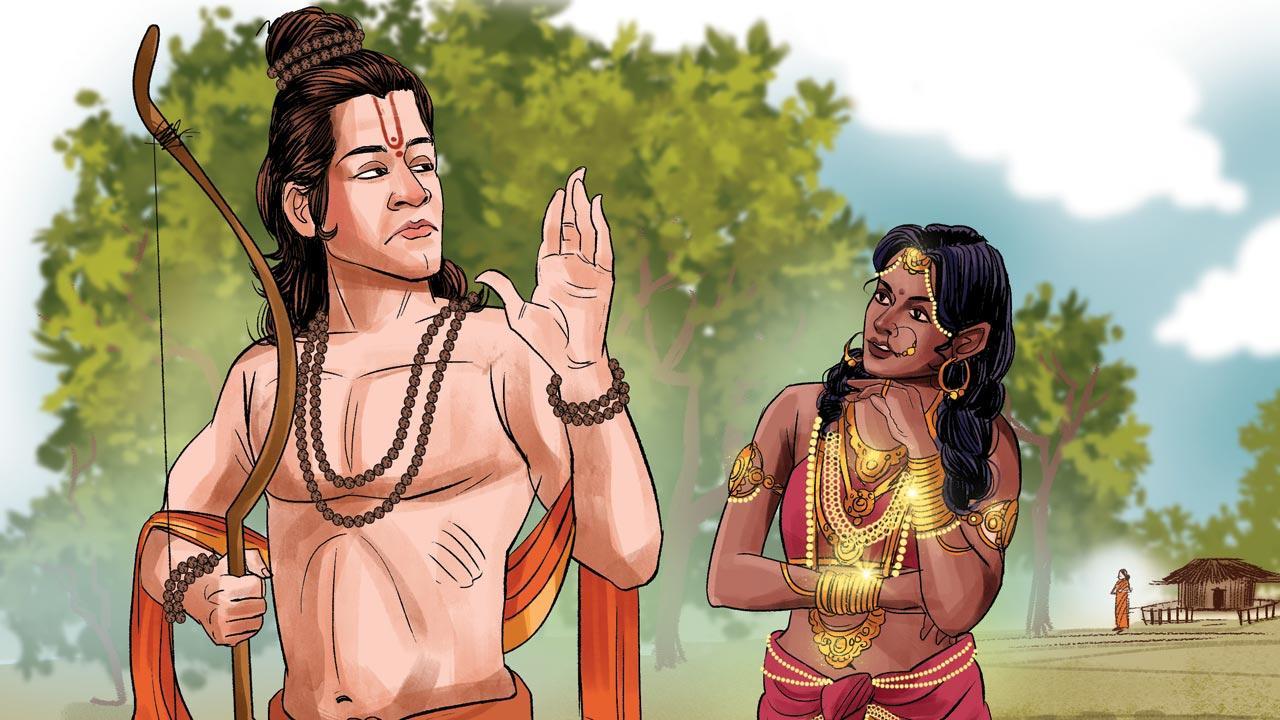

The book shows the progression of epics across cultures—whether it is the non-Sanskrit Mewati folk Mahabharata, or the Bhili Bharath adivasi oral text of the Dungri Bhils. Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() Beevi Surpanakha “dyes her scattered grey hair with charcoal and honey” and “greedily decks up with her late grand aunt’s gold”. She tracks Lama and then proposes to him. Lama invokes Shariat to evade her sexual advances. But Surpanakha asks why a woman is not allowed to keep multiple men, if the Islamic law allows men to engage with four or five women.

Beevi Surpanakha “dyes her scattered grey hair with charcoal and honey” and “greedily decks up with her late grand aunt’s gold”. She tracks Lama and then proposes to him. Lama invokes Shariat to evade her sexual advances. But Surpanakha asks why a woman is not allowed to keep multiple men, if the Islamic law allows men to engage with four or five women.

ADVERTISEMENT

The conversation between Lama and Surpanakha is laced with quick-wit and sarcasm in the indigenous Malabar Mappila language of northern Kerala spoken by Muslims. The repartee is one of the highlights of the Mappila Ramayanam, an adaptation-retelling of Valmiki Ramayana, which shares striking similarities with Mappillappattu—the 700 year-old song tradition of the Muslims of Malabar. The base language of these songs is a unique fusion of Arabic and Malayalam. Even today, children in Muslim homes are treated to Mappila isals (soothing fast notes) during bedtime. And the women, not quite empowered to speak on love and sexuality in public, find solace in quoting a Hindu epic character’s attack on patriarchy. They are happy to take recourse in a character who fights dogma.

This columnist chuckled over Surpanakha’s logic, as she read Orient BlackSwan’s new compendium titled Epic in India in which researcher Sharone K Meeran throws light on the Mappila Ramayanam which exploits the acceptability and popularity of the original Ramayana to promote regional agendas. The Mappilla text is born out of cultural engagement of the Mappilas with the Hindus; it borrows the main characters (names changed to Lama, Lavana, Anuman), but adapts to the mixed cultural milieu, acknowledging the Hindus in the vicinity.

A photograph by Dr B Hariharan of the Sreerama Pattabhishekam by the Sandarsan Kathakali Vidyalayam at the Natakasala of Sreekrishnaswamy Temple in Kerala

A photograph by Dr B Hariharan of the Sreerama Pattabhishekam by the Sandarsan Kathakali Vidyalayam at the Natakasala of Sreekrishnaswamy Temple in Kerala

Veteran folklorist TH Kunjiraman Nambiar, who put together the Mappila Ramayanam in the present form, heard it from a wandering beggar. Mappilas only entertained the “higher myths” of the Ramayana. The tribals of Wayanad district have their own version of the epic, termed Wayanadan Ramayanam. Here, many other myths are also embraced. So much for the prevalence of the hierarchy even in parallel Ramayanas!

As Meeran points out, Mappilas present Lama (Rama) as a prophet, a sultan from Kosala. He is Lavana’s (Ravana) aliyan (brother-in-law); while the plot is Puranic, the characters lead an Islamic lifestyle. Scholars state that the verses carefully and consciously weave Hindu and Muslim practices. For instance, the Karkidakam holy month is followed by Malayali Hindus as Ramayana masam; but the verses relate the recital to that of Azan, naturally tying the song ritual to offering of the namaz.

The Mappila Ramayanam wears a sardonic and irreverent form. But surprisingly, it has not triggered communal tensions in Kerala so far. On the contrary, it is being studied as a splendid example of the imaginative use of a folk form as a site of cultural resistance. It also speaks of banter-filled healthy inter-religious bonds, devoid of prejudice and hatred. It demonstrates the folk quality of humanizing god-like characters.

Like the Mappila text, Kerala’s Ezuthaccan’s Adhyatma Ramayana also positions Rama as a human and god. Rama gracefully but sarcastically thanks Kaikeyi for crowning Bharata. “It is a strain to rule/while it is easy to live in the forest/My mother is really partial towards me.”

Ezuthaccan’s Rama is respectful towards Surpanakha. The description of the rakshasi evokes pity than indignation, the text does not ridicule her passion for Rama; neither does it project Ravana as a villain.

Ezuthaccan, the 16th century figure was a sudra who approached the epic from a different perspective. He saw an empowerment in the retelling, an act of rebellion against the caste system.

Epic in India offers a collector’s volume of literary traditions, translations, revisits, adaptations (of form and content), re-readings—a cultural continuum which shapes and is shaped by the epic. The panoramic view of the epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata) is put together by Professor Tutun Mukherjee and Professor Bharathi Harishankar. They show the progression of epics across cultures—be it the non-Sanskrit Mewati folk Mahabharata, the Bhili Bharath adivasi oral text of the Dungri Bhils, the Ramkatha adaptations in North-East India, not to forget the versions of Tibetan Ramayana blended with the local political ethos, with patronage from Buddhist monasteries and lama historians.

Translation and redoing of Indian texts was at its peak after the eleventh century in Tibet. Rama was identified as an earlier incarnation of the Buddha.

The Maad Ramayana of Rajasthan is another interesting variation of the performative tradition. It is on the verge of extinction because Maad is an endangered tongue spoken in just 28 villages of Sawai Madhopur and Karauli districts. In the Maad region, farming cycles align with Ramayana performances. The collective singing of the epic happens before the monsoon when farmers/labourers can afford to sit back and relax at night. Villages compete to perform various question-answer padas. The Medhiya (male leader) sets the tone of the dance and song, after which the chorus follows.

This columnist was amused by the reflection of everyday power-equations and relationships in the Maad Ramayana songs. When Sita is trapped in the waters of Jamuna, she asks the crow to play messenger, but with caution. She doesn’t want the news to travel to her sister-in-law, as the latter will only laugh at the crisis; also not to her mother, who will worry needlessly. She wants the crow to meet the father and the brother, as they are in a position to help.

Unfortunately, women are not allowed to perform in the Maad region, as per panchayat rules. Men portray women. Women are part of the audience which cheers and greets Ram Ramsa! Interestingly, Jai Shree Ram is not in currency, despite the wider political preference for the popular salutation!

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!