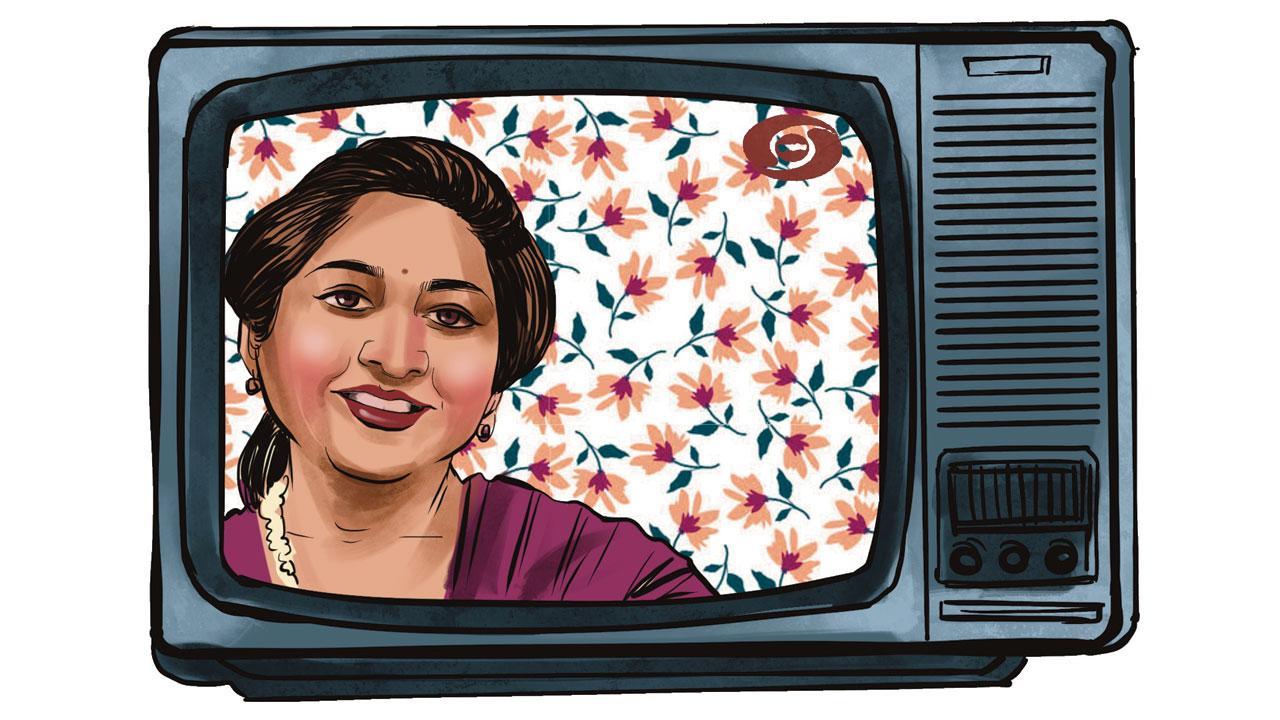

Tabassum anchored Indian television’s first talk show in 1972, featuring interviews with film personalities, interspersed with clips from their work

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() If I had to choose one word to describe the opening credits of the television show (then called programme) Phool Khile Hain Gulshan Gulshan (The Gardens Bloom with Endless Flowers) it would be: giddy. In contrast with Doordarshan’s state-ly pace, this montage of swans, bees and time-lapse blooming flowers had the rhythm of a flitting butterfly. It typified popular cinema as a garden of pleasures, a sensual variety show, like Nature. Giddy too was the presence of Tabassum, its anchor, exuding old-world adakari, all nayan matakka, mouth movements, exaggerated giggles, shayari and lateefay (a word I learned from the show).

If I had to choose one word to describe the opening credits of the television show (then called programme) Phool Khile Hain Gulshan Gulshan (The Gardens Bloom with Endless Flowers) it would be: giddy. In contrast with Doordarshan’s state-ly pace, this montage of swans, bees and time-lapse blooming flowers had the rhythm of a flitting butterfly. It typified popular cinema as a garden of pleasures, a sensual variety show, like Nature. Giddy too was the presence of Tabassum, its anchor, exuding old-world adakari, all nayan matakka, mouth movements, exaggerated giggles, shayari and lateefay (a word I learned from the show).

ADVERTISEMENT

Tabassum anchored Indian television’s first talk show in 1972, featuring interviews with film personalities, interspersed with clips from their work. In state television’s spartan landscape the show, along with Chitrahar, made us into gulab jamuns, soaking up the intimacy with movie people, plump with abandonment and pleasure. Tabassum began as a child actor. Like many child actors, she was unable to transition to a successful adult career in films, but pivoted zestfully to a new medium, working in radio, television and social media through her lengthy career.

Tabassum’s show was an oral history of a contemporary medium not considered respectable, or worth studying until very recently. It was an industry that grew informally, through the energies of practitioners, rather than institutions. In continuity with that, movie people also led unconventional Indian lives. It is complex to record unconventional lives, work, worlds or relationships, because these are constantly unfolding, revealing new meanings of what life can be, outside an existing vocabulary. Perhaps their unprecedented nature can be apprehended best in conversations—open and fecund like gardens, unruly in places, manicured in others, blooming with insights, sowing seeds for later understanding. Tabassum’s interviews, which probed personal life—extra marital affairs, disappointments, encounters—as well as craft, success and working relationships, were an integrated record of this kind.

The barely-observed history of women in media reveals a different social history of media, women, and India. Tabassum’s career began with the nation in 1947. Born in a marriage between a freedom fighter and an Urdu journalist, she was named Tabassum by her Hindu father and Kiran Bala by her Muslim mother, expressing mutual love and respect. She told the story of her entry into films as a chance thing. Financial need may have driven it, but it also reveals the relationships between the world of letters and the world of cinema that was part of Bombay life—a fluid Hindustani world, which Phool Khile Hain inserted into Doordarshan’s imagination of nation.

Tabassum pioneered a form taken forward by Rendezvous with Simi Garewal, with a significant difference. Her guests were not just A-list celebrities. She interviewed people as diverse as Jeevan and Dilip Kumar, Anand Bakshi and Prem Chopra. Where later shows aimed for exclusiveness, her show strove for polyglot inclusion, propelled by passion for the film industry, maybe even her marginalisation by it; a love as fulsome as the rose in her hair.

What did the presence of such a figure on national television engender? The seeds of growth took root with her? That requires not just a different history—it requires a different way of telling history. Who is up for it? Who is up to it? Not super-sponsored KJo Koffee parlour, nor the arid cinephilia-as-listicle of Instagram, I think.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at paromita.vohra@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!