Konkani writer Damodar Mauzo’s new collection of stories, populated by Goa’s cab drivers, tiatrists, and estate agents, underlines his interest in the drama of everydayness

Damodar Mauzo, 77, a foremost Konkani language advocate, equally treasures multi-lingual exchanges

![]() Yasin, Austin, Yatin. Take your pick. The choice is offered by this year’s Jnanpith award-winning Konkani writer Damodar Mauzo. In his new anthology, The Wait and Other Stories, he tells us the story of an endearing Goa cab driver who, while doubling up as a tourist guide, assumes diverse religious identities to “serve” his heterogeneous clients. As a Yasin, he recounts the glorious history of the Ponda Safa Masjid. As an Austin, he drives his guests to Palacio de Idalcao to celebrate Alfonso de Albuquerque’s defeat of the cruel Adil Shah. And as a Yatin, he concentrates on completely different bylanes of history, steering more towards temple precincts. Depending on the tourist, he decides if he will broach religious conversions, or refer to the civic imperative of beach cleaning.

Yasin, Austin, Yatin. Take your pick. The choice is offered by this year’s Jnanpith award-winning Konkani writer Damodar Mauzo. In his new anthology, The Wait and Other Stories, he tells us the story of an endearing Goa cab driver who, while doubling up as a tourist guide, assumes diverse religious identities to “serve” his heterogeneous clients. As a Yasin, he recounts the glorious history of the Ponda Safa Masjid. As an Austin, he drives his guests to Palacio de Idalcao to celebrate Alfonso de Albuquerque’s defeat of the cruel Adil Shah. And as a Yatin, he concentrates on completely different bylanes of history, steering more towards temple precincts. Depending on the tourist, he decides if he will broach religious conversions, or refer to the civic imperative of beach cleaning.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mauzo’s driver hero, like most other characters the writer has given birth to since 1971, represents a quintessential part of Goa’s soul. He is a character modelled on many real-life drivers who are polyglots, adept at small talk, alive to non-verbal social cues, and eminently likeable. Even when these drivers spin sellable tales around the iconic Basilica of Bom Jesus or plug for the newly-built Mahalasa Narayani temple at Verna, they have a worldview on offer. It is impossible to miss their perspectives, whether you visit Goa for work or leisure. This columnist has been fortunate to avail of the lens provided by these “guides” who ask: “Raikar? That’s a Goan name, right? My aunt’s landlord was a Raikar.” Communication can never go wrong, when the personal is warmly interwoven in the political.

The Wait and Other Stories (Penguin Random House India, translated into English by Xavier Cota) has come out at an eventful juncture in Goa’s social-political life. The BJP has formed the government for the third consecutive time in Goa, thereby weakening an already sidelined Congress party. Goa’s embrace of a party advocating the Hindutva ideology surprised many, since the state’s Christian population had voted differently in the past. Many argue till date that native Goans (of any religion) are not voting for a particular party, but are essentially seeking leaders who deliver on civic fronts. Meanwhile, Goa’s tourism industry is doing well in the post-COVID dynamic, particularly the “starred” hotel havens, which have fetched a high occupancy rate. Needless to add, hope is in the air for the Yasins, Austins, and Yatins who depend on the influx of tourists for their daily bread.

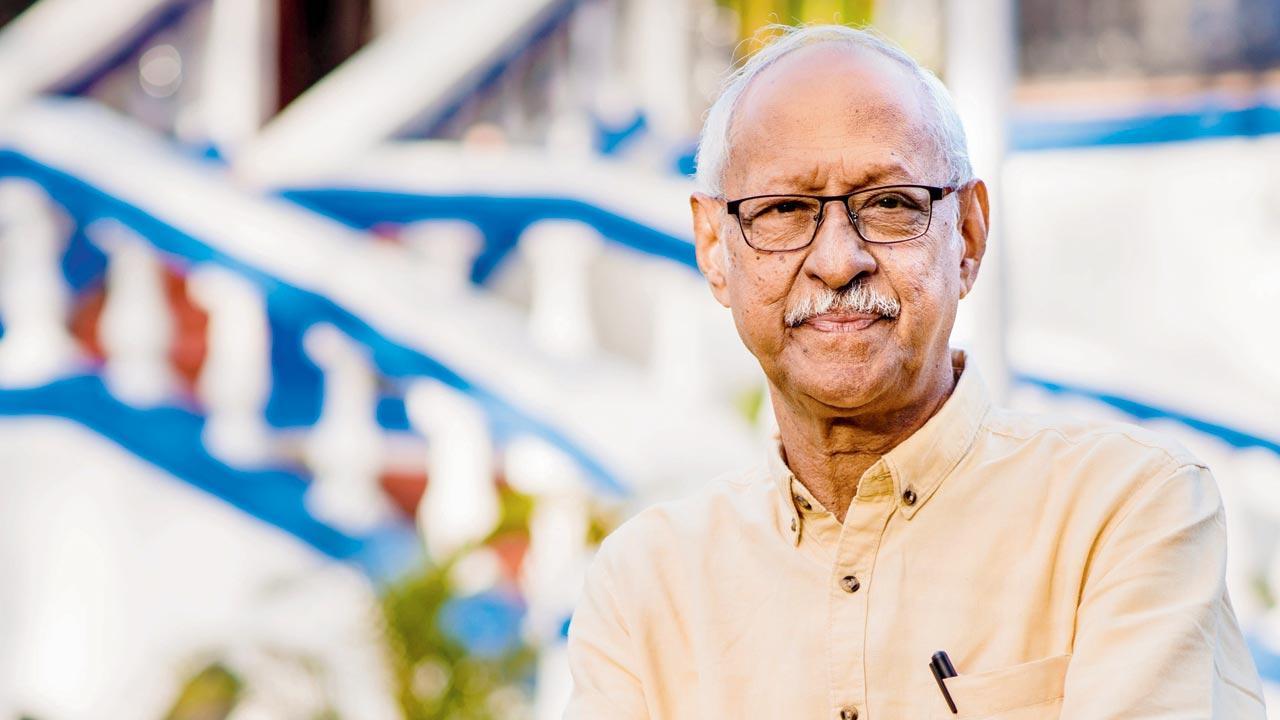

Mauzo at the Goa launch of his just released book, The Wait and Other Stories, translated by Xavier Cota. Pics courtesy/Sunaparanta Goa Centre For The Arts

Mauzo at the Goa launch of his just released book, The Wait and Other Stories, translated by Xavier Cota. Pics courtesy/Sunaparanta Goa Centre For The Arts

Mauzo presents an assortment of quirky, funny, loving (some evil too) characters, while they are negotiating their individual trajectories in a post-2014 Goa. Most stories are written between 2014 and 2020, available first in the Konkani collection Tishthavani in July 2021. While the majority capture everyday life in Goa, one is backdropped against the Kargil conflict, and another set in high-brow Mumbai. However, stories, whether set in Goa or not, point at universal Indian experiences. For instance, Burger captures two school-going girls (Irene and Sharmila) who bond over Oliver Twist and beef burgers. They are oblivious of the political sensitivity attached to beef-eating in contemporary India. The tiffin box exchange underlines the warm multicultural give-and-take of early school years.

Without making an overt statement on tolerance, diversity and mutual respect, Mauzo treats the reader to tender moments in a polarised and charged world. “Most things have simple solutions, unless the intention is to complicate,” observes the Jnanpith awardee whose literature and life have drawn from relationships that go beyond class, caste, region, race and religion. In fact, his short stories and novels derive their real-life edge from a deep connect with the people around him. He has always been an approachable literary figure; he is among those activists who suffered lathi blows to secure an independent language status for Konkani. As the lore goes, Mauzo meets the real-life editions of all his literary characters—including the much-feted and widely-translated central character Karmelin—in his village grocery shop at Majorda, which he manned until 2018. The hero of Tsumani Simon as well as the lead from the latest surreal piece of fiction, Jeev Divum Kai Chya Marum (Konkani), sprung to life from Mauzo’s neighbourhood. Mumbai’s Majestic Prakashan is soon going to publish Jeev Dyava ki Chaha Ghyava, rendered in Marathi by Mauzo’s wife. Jerry Pinto’s English version of Jeev Divum... is also due next year. The Kannada version was published last year by Bahuvachana.

Mauzo’s characters spring from Goa’s distinct locales, as is demonstrated in The Wait And Other stories where the lead figures seem super-identifiable—landlords teaching Portuguese, carpenters working on five-star properties, an estate agent pining for the love of his life, a tourist couple at Panjim’s Mahalakshmi temple, a Bhatkar counting coconuts in his storehouse and a tiatrist rehearsing for D-day. Action is situated in distinctly local milieus like the Benaulim church Mass, Vasco-Howrah Rail highway, Dona Paula headland, Cansaulim Bazaar, Ramnathi Parking lot and Murmogao harbour.

As Panaji-based editor-author Sandesh Prabhudesai remarks, Bhaiee—as Mauzo is popularly called—doesn’t mirror Goa’s exotic tourist destinations and resorts. “He leaves that stuff for the TV channels. For Bhaiee, the drama is in the everyday routines and characters.” Mauzo celebrates the varying local flavours of Marathi, Konkani, Portuguese and Goan English. He speaks four languages and connects personally with the Goan Catholic neighbourhood, a milieu where he has spent a lifetime, except for a small span when he shifted to Mumbai for graduation.

Mauzo, 77, a foremost Konkani language advocate, equally treasures multi-lingual exchanges, as demonstrated in his keen leadership at various lit fests in Goa as well as the guest presence in the latest Marathi Sahitya Sammelan. As a writer, his regional identity is not premised on parochial parameters. In fact, he communicates lucidly in English, like he did in Ink of Dissent (2019), a collage of essays on bigotry, bias and freedom of expression.

Writer Xavier Cota, Mauzo’s preferred translator for four decades, rejoices in Mauzo’s evolution as a local-global litterateur. “At this point Mauzo is a sought-after name. He travels across India for literary events, but our friendship dates back to pre-Internet pre-Google Translate.” Whenever Cota takes on any translation of Mauzo, the duo chat indefinitely over the text, context, and subtext. The translator lives in adjoining Betalbatim, so a query can be settled over a phone call or less than a ten-minute drive. Mauzo is known for his famed break-neck speed writing. He writes his stories generally at a single sitting and often sends them to the publisher without re-reading them. “Remarkably, they are perfect. His Konkani readership is loyal and often not critical. But whilst translating his creations, if I [rarely] find an error, or need clarifications, we fix it together. We have to be careful because many readers read and compare both the versions. I need his nod to stray away from the original, in the interest of accuracy.” Cota recalls that at one point, when Mauzo’s readership was limited to Konkani readers from Goa, the literature had references which would cut no ice with non-Goans. “As a translator, it was my duty to interpret the situation for a pan-Indian reader. Now of course, he connects with a wide international readership.”

As Mauzo travels across the length and breadth of India, well-wishers and friends worry about his safety, especially the wrath incurred by his outspoken views on personal liberties and freedom of expression. The writer doesn’t share the anxiety and fear about a possible attack on his life. “As a writer, we cannot dwell on unseen dangers. We have to speak our minds, we have to wage our battles, however unpopular they may be,” says Mauzo who is perennially accompanied by security guards at most public events. Interestingly, Mauzo was asked recently if his next work of art will dwell on security personnel. “I have made friends with them. They may pop out of my manuscripts one day soon.”

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!