A unique music-art project takes 21 Hindustani and Carnatic classical musicians off a concert stage and positions them in environmentally vulnerable places

TM Krishna during his performance at Tuensang, Nagaland

The minute we say classical — in literature, dance, music or art — a set of grandiose stipulations nudge our consciousness. Of proper attire, solemn invocation and august appreciation, the stage probably is the lynchpin to a concert’s structure. But will music not enrapture listeners past ‘the comfortable’? First Edition Arts (FEA) is surveying the prospects of that question. The Mumbai-based art group has been experimenting with innovative formats for the past six years. “Our work stems from our belief in documenting art. That’s how or why we started filming Indian classical music,” says Devina Dutt, co-founder at FEA. The Blue Planet series, an unusual compilation, travels with 21 Hindustani and Carnatic classical musicians to 20 different spots in the country that call for ecological consciousness. From the most polluted neighbourhood of Ennore in Chennai to the neglected Tuensang village in Nagaland, the project is hunting down music’s role in the wider world.

ADVERTISEMENT

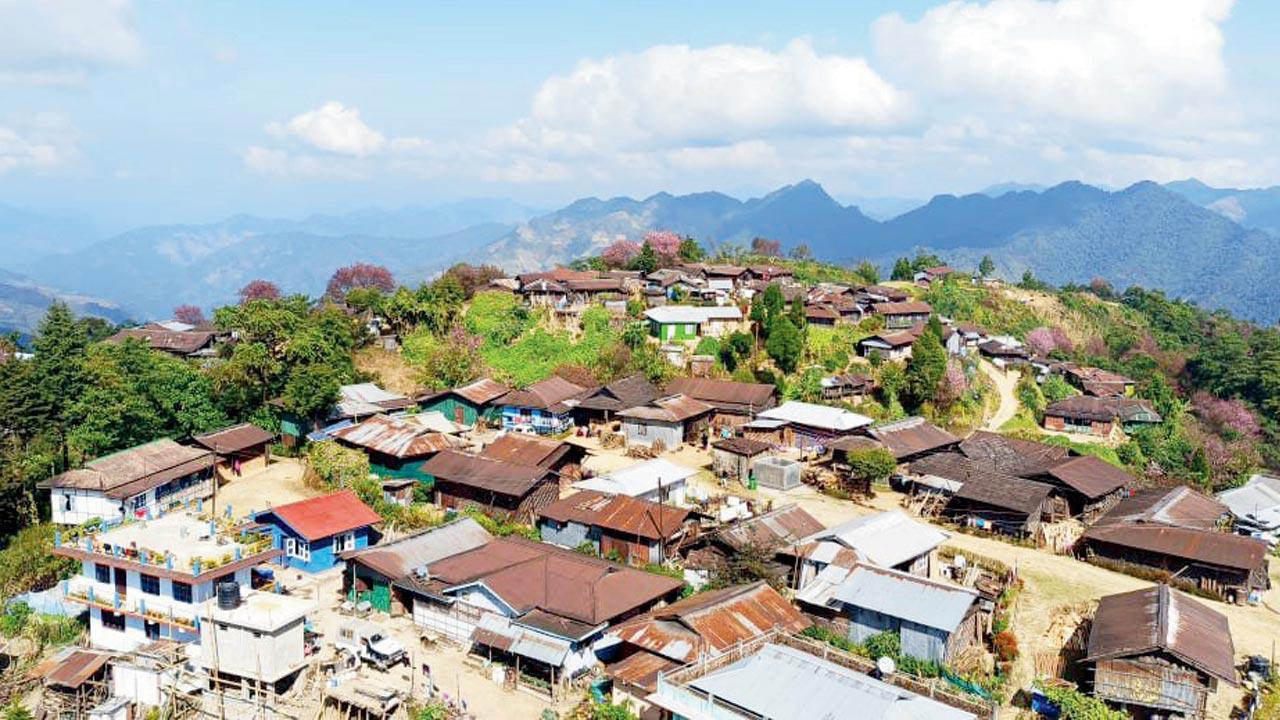

Tuensang village in Nagaland. pics/first edition arts

Tuensang village in Nagaland. pics/first edition arts

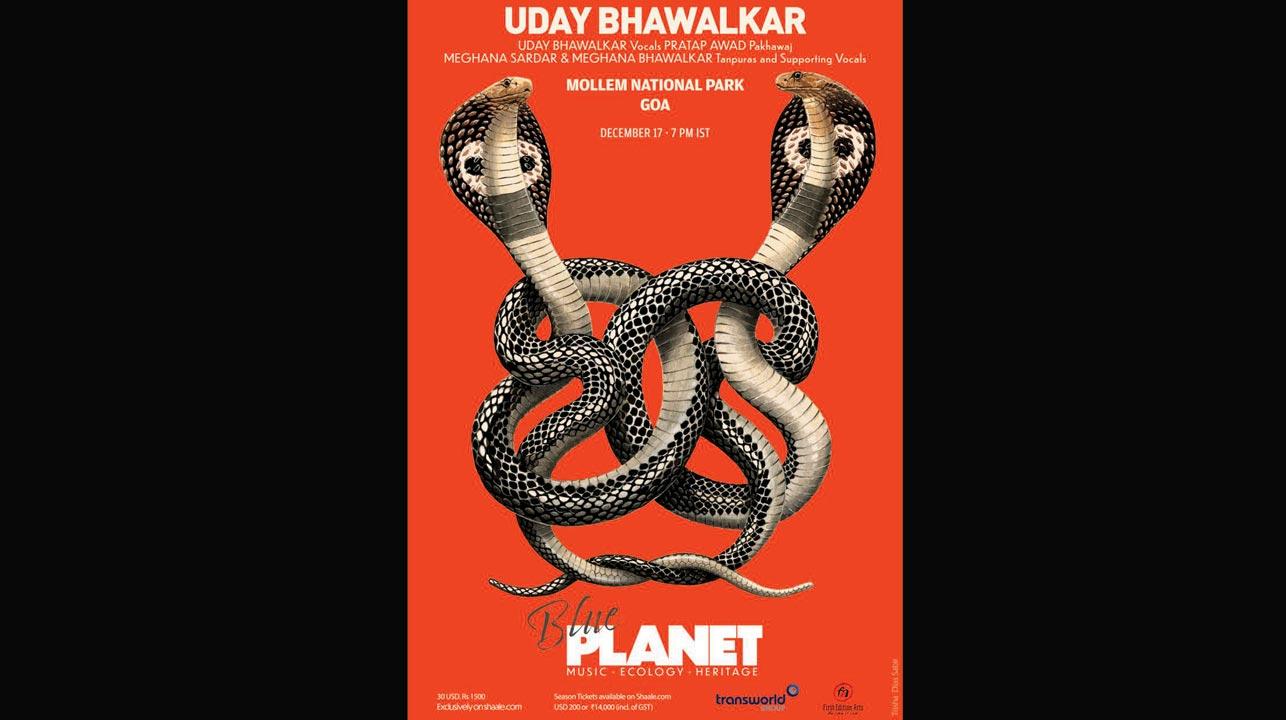

Dutt talks about the pandemic as a vital reference point to the conception of this series: “The virus had made on-stage performances impossible, but we didn’t want the virtual medium to render music through boxy cameras alone. That tries to replicate a performance without its physical offerings. We wanted to toy with the film medium’s potential, and as a group, exploring alternative spaces for traditional music has also been our defining characteristic.” At around the same time, Dutt caught notice of the Aamchi Mollem campaign in Goa, a people’s collective fighting clearances accorded to a railway line, a highway and a transmission line that would’ve cut through the forests of Mollem National Park. “I saw how young artists and illustrators collaborated and made art to garner awareness about the cause. I am a believer of the inter-disciplinary qualities of art, so, the Blue Planet art project and music series happened.”

Ramakrishnan Murthy with marine conservationist Gabriella D’Cruz at Goa tide pools

Ramakrishnan Murthy with marine conservationist Gabriella D’Cruz at Goa tide pools

The series visits locales that symbolise our need to align politics with climate action. When TM Krishna seats himself on a bamboo machan in Tuensang, locals are curious to know what’s happening. They are new to this kind of music but have welcomed musical visitors over tea and chatter. Dutt explains this rare juxtaposition aims to gather newer audiences, and change our approach to concerts. The project that will extend until April with two episodes being released every two weeks has also made musicians encounter their ethics and ecological stance. When Dutt approached Pandit Venkatesh Kumar to step out of Dharwad in Karnataka, and perform amidst local communities, he was unwilling. It took two to three months of cajoling before the maestro realised he was only reconnecting with his inherent belief of breathing the cool air of his home town (Dharwad). “Finally, he came on board with our filming process and performed in a mango and jackfruit orchard in the area. After the performance, I told him that he seemed to be exceptionally inspired, and Kumar agreed that the environment influences his singing.”

A poster from the Blue Planet art project

A poster from the Blue Planet art project

Dutt hopes to return with the series as areas in northern India, like the Himalayas, remain undiscovered from their lens. But for now, audiences have two chunky nuggets to digest — Indian classical music is not only for elite private spheres, and it should clearly attach itself to ecological conservation in hilly northeastern India, the forest lands of Western Ghats or preservation of coastal micro habitats in Goa tide pools and the Sunderbans.

Log on to shaale.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!