Mumbai-based Film Heritage Foundation is among the world institutions that recently partnered to restore G. Aravindan’s folk fantasy film and showcase it at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in July. Its founder Shivendra Dungarpur discusses his travels to Kerala to secure two 35 mm prints and the Malayalam filmmaker's unique appeal

- 35 mm Release Print (1)_d.jpg)

The 35 mm prints of 1979 Malayalam film 'Kummatty', directed by G Aravindan. Photo: Film Heritage Foundation

Over the last few years, the influence and luxury of streaming platforms has given more people the chance to explore films in various Indian languages, going beyond the popular Hindi or Bollywood cinema. These are mainly from the Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu cinema industries, which are known to produce some of the country’s most experimental and entertaining films. However, even long before people had access to streaming platforms, there were many cinematic gems being produced in those regions, which aren’t easily available today. This highlights the need for film preservation and restoration, especially to showcase India’s rich film history.

ADVERTISEMENT

In one such attempt, the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) in Mumbai collaborated with Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation, which runs the restoration programme ‘World Cinema Project’ and Italy’s Cineteca di Bologna to restore the classic 1979 Malayalam film ‘Kummatty’, made by G Aravindan. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the city-based archive met with K. Ravindranathan Nair, founder of General Pictures, which produced many of Aravindan’s films and secured permission to access the film’s prints from the National Film Archive of India (NFAI). The film was restored by the L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in Bologna in Italy from two surviving 35 mm prints that had gathered dirt, scratches, and glitches over time.

The restored film was showcased at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Italy earlier this week.

Mid-day.com spoke to Film Heritage Foundation founder Dungarpur to understand how the film was restored and the challenges faced while doing it. He talks about why G Aravindan’s film was chosen for revival, his meeting with producer K Ravindranathan Nair and the filmmaker’s son Ramu Aravindan, as well as plans for restoring other regional Indian films.

Shivendra Singh Dungarpur met with General Pictures producer K Ravindranathan Nair in February 2020. Photo: Film Heritage Foundation

Here are edited excerpts from the interview:

Tell us about the journey to Kerala and the process of sourcing ‘Kummatty’. How did the meeting with G Aravindan’s son Ramu Aravindan help?

I discovered G. Aravindan’s films when I was a student at the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune and they left a deep impression on me. When I was introduced to the world of film restoration, I knew that G. Aravindan’s films were a priority on my wish list to be restored. It was about three years ago that I first spoke to Bina Paul, the artistic director of the International Film Festival of Kerala, about my dream to restore his films. She introduced me to his son Ramu Aravindan who in turn introduced me to the producer, K. Ravindranathan Nair. Nair was an unusual producer. A businessman helming a cashew export business, he is credited with being a patron of arthouse cinema in Kerala, having produced five films of G. Aravindan and four films of Adoor Gopalakrishnan – films that are considered landmarks in Malayalam cinema even today. I had heard that he financed the films but did not interfere in the production, giving the filmmakers complete creative freedom. I was keen to meet the maverick producer and after almost a year of emails and calls with his son Prakash, he finally agreed to meet me. I travelled to Kollam in Kerala on February 1, 2020 to meet Nair and broach the topic of the restoration of two of Aravindan’s films ‘Kummatty’ (1979) and ‘Thampu’ (1978). He and his son Prakash received me very graciously and he readily gave his permission to restore the films. He promptly issued all the formal letters and NOCs and has been supportive.

What makes ‘Kummatty’ and G Aravindan’s filmmaking unique and important? Are there plans to show the restored film here?

I would like to quote G. Aravindan himself when he was asked about his film ‘Kummatty’ (1979). He said, “Kummatty arrives like the seasons. He represents spring. He comes in fact in spring when the rain is over and the plants are green and in bloom. He is part of that nature.” This quote itself describes the filmmaking of Aravindan, in my opinion, one of India’s greatest masters alongside Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak and one of the leading exponents of Malayalam cinema and the Indian New Wave.

G. Aravindan had an unusual path to filmmaking. He began his career as a professional cartoonist and worked as an officer with the revenue board before making his first film ‘Uttarayanam’ in 1974. His uniqueness lay in creating poetry on celluloid through his tranquility and silence, almost a language of its own, so deeply influenced by the landscape, folk art and culture around him. His cinema is like a mirror reflecting reality as well as its magic. Each of his films, whether it is ‘Kanchana Sita’ (1977), ‘Kummatty’ (1979), ‘Chidambaram’ (1985) or ‘Thampu’ (1978) is different. As a matter of fact, he was known for experimenting with the cinematic form in every film and eschewed a consistent style. As Aravindan once told the journalist Sadanand Menon, “My ultimate in the art form is the North Indian Raga Alapana, whose only meaning is the satisfaction and the tranquillity it conveys.”

The whole idea of restoring a film is to give it a new life. So, the film will definitely be screened on festivals and every other available platform if possible.

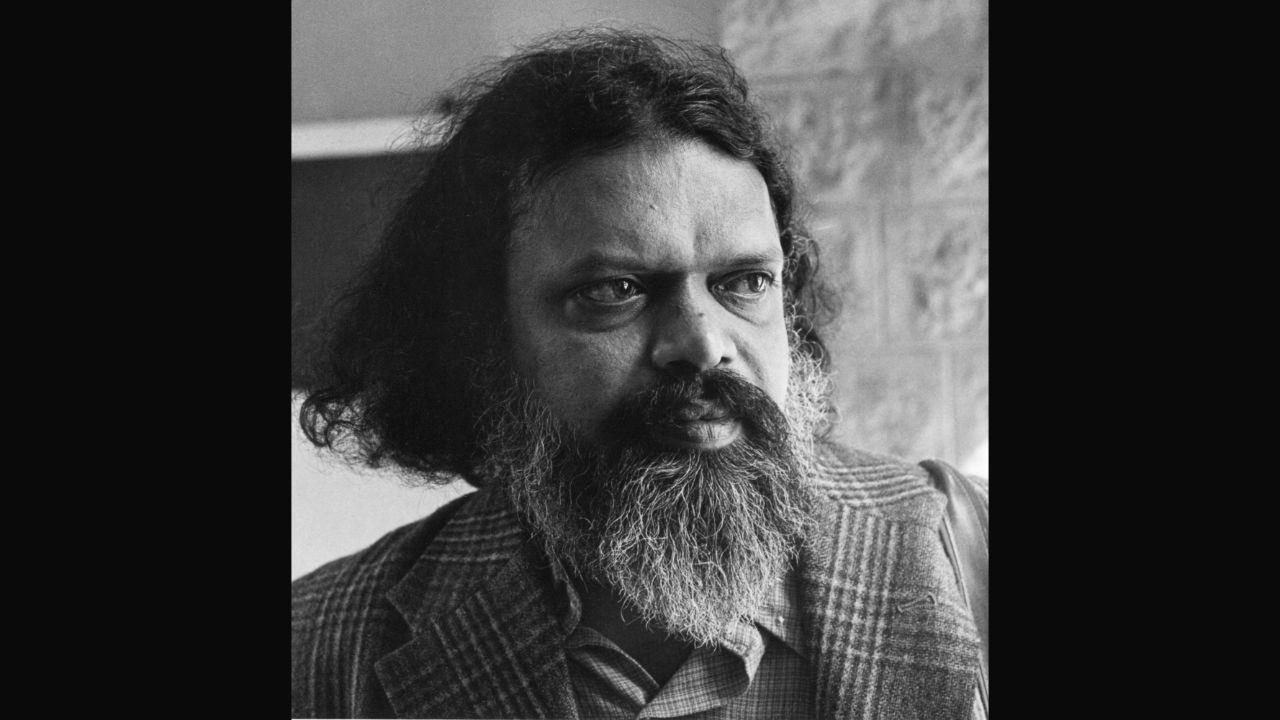

Malayalam film director G Aravindan, who made the 1979 film 'Kummatty'. Photo: Film Heritage Foundation

How did this collaboration between the Film Heritage Foundation, the World Cinema Project by Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation, and Cineteca di Bologna come about?

In 2009, I happened to read an interview with filmmaker Martin Scorsese, which, looking back, first triggered my interest in film preservation and restoration. Martin Scorsese spoke about the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, Italy dedicated to restored films. I had never come across the idea of a restored film festival before and my curiosity drew me to attend the festival in 2010. It was an eye-opener. I discovered a whole new world of film archivists and restorers who were dedicated to preserving and restoring films rather than making films.

It was in Bologna that I connected with Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation and was told that they had been trying to get the reels of the film ‘Kalpana’ (1948) directed by Uday Shankar (the brother of Pandit Ravi Shankar) out of India for restoration for almost three years but had not succeeded. I told them that I would help them and managed to send the cans to Italy for restoration in about three months. The restored film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012 and I was invited to walk the red carpet with Amala Shankar, the wife of Uday Shankar and the star of the film. Subsequently, I worked with them on the restoration of the great Sri Lankan filmmaker Lester James Peries’ classic film‘, Nidhanaya’ (1972), which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2013.

Being a filmmaker myself, I realised that as artists, we are so immersed in creating our works that we tend to forget about the future of the work we create. My whole perspective changed during the making of my film ‘Celluloid Man’ (2012) that pays tribute to PK Nair, India’s legendary film archivist, when I discovered the colossal loss of our film heritage. I realised that I couldn’t stop at the film and that I needed to do something concrete to take up the cause of saving our endangered film heritage.

So, I established Film Heritage Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to the preservation of India’s film heritage in 2014 and we have been working closely with Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and The Film Foundation right from inception.

What was the biggest challenge in restoring ‘Kummatty’, in terms of picture and sound?

The first big challenge was finding the best source elements for the restoration. In the case of celluloid films, this is the original camera negative. But tragically no original camera negatives of any of the Aravindan films survive. We put out a call around the world to all the institution members of the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) looking for any other elements of the films so that we could select the best available elements for the restoration. We received responses from the Library of Congress in the USA and the Fukuoka Archive in Japan that they had prints, but they were not in very good condition and in the case of the prints in Japan, subtitles had been embedded into the film. Finally, we sourced two 35 mm film prints from the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) and shipped them to the L’Immagine Ritrovata lab in Bologna. These prints were not in great condition either, but we must thank the NFAI for having preserved these prints over the years, making the restoration possible. One of them was subtitled, but we were fortunate to find another print without subtitles.

The restoration itself was very challenging. On inspection, the lab found that both the prints had a lot of wear and tear and were very dirty and deeply scratched. One of the prints presented a consistent vertical green line on the right-hand side of the image, which required painstaking frame-by-frame manual work to be removed. The colour of the positive was decayed and the film’s natural environment, an essential character of the film, had completely lost its rich palette of skies, grasslands and foliage and become all magenta presenting a real challenge for the technician working on the colour grading. One of the principles of ethical film restoration is that one has to stay true to the original creator’s vision. With this in mind, we had both Shaji N. Karun, the cinematographer on the film and Ramu Aravindan on long calls with the colourist in Bologna to ensure that the original aesthetics of the film were honoured to the best possible standard. Doing this remotely over Zoom calls and checking file transfers was a long and arduous process. Sound design is also a crucial element in Aravindan’s films and many hours were spent cleaning up the sound.

A still from the restored 1979 Malayalam film 'Kummatty', which premiered at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival earlier this week. Photo: Film Heritage Foundation

Why do you feel that G Aravindran’s films haven’t got the recognition they deserve and why is there a lack of circulation? What can you tell us about the plans of restoration for ‘Thampu’ (1978)?

G. Aravindan has a great stature in Kerala and also internationally – renowned Japanese film critic Tadao Sato once said that ‘Kummatty’ (1978) was the most beautiful film he had ever seen. Thanks to this recognition, several archives in Japan began collecting prints of his films. However, I think because he passed away at such an early age and also because his films were not shown as much in the rest of India, I feel he didn’t get his due. Also, as I mentioned the original camera negatives of his film are lost and the prints are not in great condition. Hence, the restoration of ‘Kummatty’ (1979) and ‘Thampu’ (1978) will revive the circulation of the films and give them a new life.

Which are the other Indian films you think should be restored?

Film Heritage Foundation’s first publication ‘From Darkness Into Light: Perspectives on Film Preservation and Restoration’ includes a list of the 60 Most Endangered Films in India which should be urgently restored. While we would love to restore as many Indian films as possible, in the short run, we will be working on the restoration of G. Aravindan’s ‘Thampu’ (1978) and we would like to also restore Aribam Syam Sharma’s ‘Ishanou’ (1990), Kumar Shahani’s ‘Maya Darpan’ (1972) and Shyam Benegal’s ‘Mandi’ (1983).

Also Read: How Mumbai-based teens turned plastic waste into a shelter for stray dogs

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!