Ahead of the release of octogenarian dance guru, Dr Kanak Rele’s biography, the doyenne speaks exclusively to mid-day about weaving together the story of a life dedicated to classical art

Dr Kanak Rele. Pic/Shadab Khan

Why did it take so long for this biography to launch?

These things can’t be planned. My family and disciples have all been hankering after me to pen an autobiography. Since there’s already a feature-length autobiographical documentary, I kept putting it off. During the pandemic my niece Radha Khambati agreed to work on this biography under my watch.

ADVERTISEMENT

Many feel recognition take its time finding you…

Isn’t it bigger than any recognition and award that people think so? For seven-long decades, I have pursued dance with my heart and soul without hankering after fame. I built Nalanda Dance Research Centre against all odds. While the Gujarat government’s Gaurav Puraskar (1989), Padma Shri (1990), Kalidas Sanmaan (2006), Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2010), Padma Bhushan (2013), and the Kerala government’s Gopinath award (2018) are vindication that I’m on the right path, it’s best to be detached about these things.

Your family has no connection with the performing arts, and yet you chose dance.

It was the other way round. Dance chose me. Unmindful of my resistance, it took me in its embrace—a space that I will enjoy till my last breath. My mother’s family of fierce Gandhians were next door neighbours to the Tatas at Altamount Road. When widowed at 21, her maternal family brought her back home. I was barely 10. To help her out of her sorrow, my maama, Madhukar, took us with him to Shantiniketan where he was learning painting with Satyajit Ray and Nandlal Bose

as classmates.

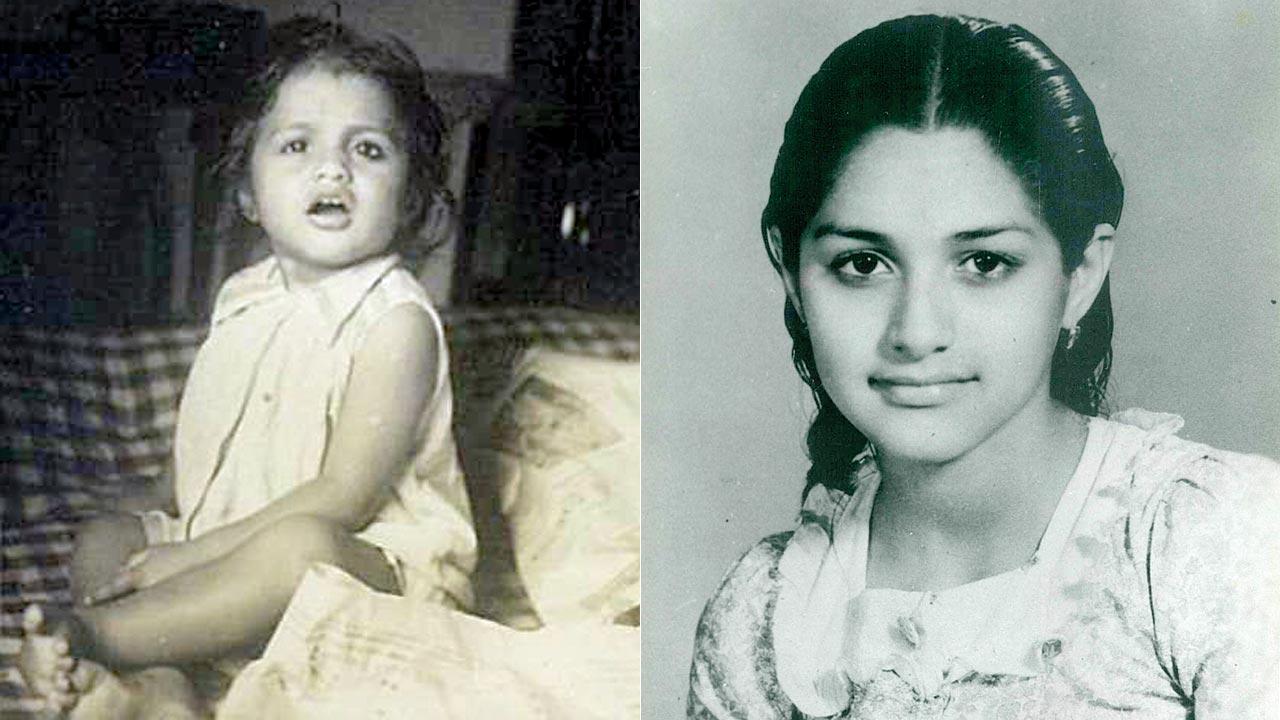

(Left) Dr Rele says that dance chose her. “I wanted to dance but mom said, no.” Her maternal uncle brought Kathakali dancer Raghavan Nair to stay with them and teach, but no one wanted to learn the alien ‘rakshas nritya’, so her maama made her his disciple; (right) At Shantiniketan with her mother, Dr Rele, 10, absorbed a mix of culture, fine arts and performing arts. “The idea of questioning everything would leave a deep, indelible mark on me,” she says. Pics courtesy/Dr Kanak Rele

(Left) Dr Rele says that dance chose her. “I wanted to dance but mom said, no.” Her maternal uncle brought Kathakali dancer Raghavan Nair to stay with them and teach, but no one wanted to learn the alien ‘rakshas nritya’, so her maama made her his disciple; (right) At Shantiniketan with her mother, Dr Rele, 10, absorbed a mix of culture, fine arts and performing arts. “The idea of questioning everything would leave a deep, indelible mark on me,” she says. Pics courtesy/Dr Kanak Rele

What did you do there?

I ran around the campus all day and often saw [Rabindranath] Tagore walking around. I used to ask my mother why this man wears gowns (laughs). The heady mix of culture, fine arts and performing arts on the campus along with the idea of questioning everything would leave a deep, indelible mark

on me.

Yet you switched from the soft lyricism of Rabindra Nritya to Kathakali?

I don’t see too much classicism in swaying both hands from the left to the right and calling it dance (demonstrates). But to each her own. My Bombay school had none of the magic of Shantiniketan. I wanted to dance but mom said, no. My maama’s group of culture buffs were into painting, theatre and dance. They invited Kathakali legend Vallathol Narayana Menon’s disciple Raghavan Nair to stay with us and teach. None of us had seen Kathakali till then. One look, and we all called it ‘rakshas nritya’. The result: Raghavan Nair had no students. He made his displeasure known, saying that he didn’t want alms. Since no one came forward to learn, maama made me a disciple. He felt it would both assuage Nair and channelise all the energy a four-year-old had.

And in a year, you were training under his guru Panchali Karunakar Panicker.

Yes. Raghavan Nair’s guru was also his father-in-law. Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad of Baroda was his patron. This Kathakali maestro was training not only the princesses of the royal family, but also daughters of several courtiers. When they married, he was left with no disciples and came to Bombay.

After a traditional welcome to our home, mom called me to bow, but I crawled under a bed. Panicker then crawled towards me. Using Kathakali gestures, he made me come out. To my family’s shock, I was mimicking him gesture for gesture. He gathered me in his arms and told everyone: This one will dance. I trained rigorously under him for years giving up sports since he felt pure lasya in me would be damaged.

The Kathakali dancer was introduced to Mohini Attam only after her son began school. She decided to research Mohini Attam in Kerala and a Sangeet Natak Akademi grant helped

The Kathakali dancer was introduced to Mohini Attam only after her son began school. She decided to research Mohini Attam in Kerala and a Sangeet Natak Akademi grant helped

But you graduated in law at the Manchester University pursuing aviation law?

My family wanted me to be a doctor, but med-school left no time for dance. So, I opted out. I’d also met cricketer and fellow-Wilsonite Yatin Rele, fell in love and got engaged before leaving for university education together. I chose international law with a civil aviation major and was the only woman

in a class of 28.

Was this a break from dancing?

Can a person be told not to breathe? Apart from putting up the dance performances across the length and breadth of UK, I occasionally travelled all over Europe, performing Kathakali to recorded music.

Were your marital family and partner supportive of your dance?

Over six decades ago, when pregnant, Yatin asked me to quit. I had to nip this in the bud. Then and there. Knowing how close he is to his eight brothers, I suggested he break all ties and communication with them for good and if he did, I would stop dancing. Though stunned, he realised how important dance was to me. Since then, he has not only been supportive, but also been a close ally.

Mohinī Āttam wasn’t even part of your repertoire till then?

I first became aware of the genre after my son began school. Rajalakshmi, a Mohinī Āttam dancer, was in Bombay. Apart from my familiarity with everything Malayali because of Kathakali, the lyrical feminism of Mohinī Āttam had me hooked despite her limited repertoire, which I began learning.

But it consumed you…

Rajalakshmi’s dance whetted my appetite and I wanted more. I then decided to research

Mohinī Āttam in Kerala. A Sangeet Natak Akademi grant helped. In Kerala, Mohinī Āttam was seen as crass because of being reduced to overtly

sexual routines.

And you persevered?

Through 1970-71, Yatin and I filmed surviving exponents Kunjukuttyamma, Chinnammuamma and Kalyanikuttyamma. Except the latter, others were in their late 80s. Their remote locations ensured their styles retained the original unaffected training. I used that with the texts Natyasastra, Hastalakshanadeepika and Balaramabharatam to create my own style.

Your research later kept you in Mumbai’s Prince of Wales museum for months.

(Laughs) Mohit Chauhan headed the museum in those days. He helped me co-relate dance with sculpture. I went with Rajalakshmi and some musicians on the days the museum was shut. While the housekeeping got busy, I’d choreograph my ashtanayikas in front of the sculptures representing them.

What do you feel about efforts by some classical dancers at introducing popular movements?

Don’t give up classicism for cheap popularity. What is portrayed as classical dance on reality shows, makes me cringe.

When you look back, are you satisfied?

How can a seeker ever be satisfied? Like all the arts, dance too is an ocean. Every dive only yields a pearl or two.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!